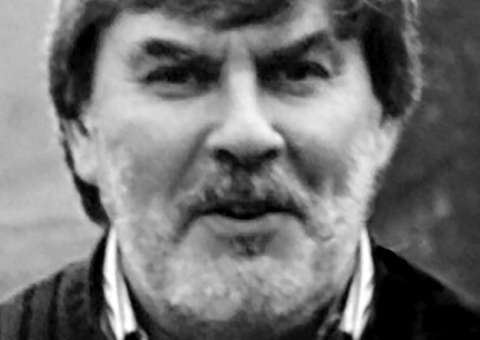

It always seemed to his friends that even the direst day could suddenly be redeemed when a door opened wide to admit the benign, cheerful, cherubic presence of the journalist Derek Brown, who has died suddenly aged 63. A gentle, genial, good-humoured, humorous man, as generous in spirit as in appearance, his consistently entertaining flood of talk reflected his vast enthusiasms.

A taste for good food and drink, and buns in particular (his idea of a perfect breakfast was a cafe in Dublin where buns were stacked up at one's table); for holidays with his wife, Eileen, and with friends at home and abroad; for public transport, and latterly for journeys made with his freedom pass on country buses from his adopted home town of Leominster in Herefordshire; for the islands around the British coast which he and Eileen had begun to explore; and for cricket, and particularly cricket statistics. A fondness for good pubs and hotels, those favourite haunts of reporters. A long-standing allegiance to the Liberal party (though less so, latterly). But above all, a love for words, and what one could do with them, their potential, but also their music; and for books of all kinds, and the shops that sell them, though perhaps most of all for old-fashioned adventure stories for boys (he had thought of writing the life of one of that art's great practitioners, Percy F Westerman).

He seemed at first sight, as he ambled amiably towards you, utterly English; sprung, you might have supposed, from a yeoman stock from somewhere such as Herefordshire. In fact he was Scottish: born at Bearsden, Glasgow, and brought up there until the age of 11, when his father, a travelling sales rep for magazines, and mother, a hairdresser, moved to Lancashire, where his schooldays at King George V school, Southport, eroded the last trace of a Scottish accent. He left school after A-levels, at first taking on a series of apparently aimless jobs: bus driver, fish-frier, stagehand. Derek's taste for flamboyant hats sometimes suggested a thespian manqué, but that was never to be. His ambition was always journalism, and specifically the journalism of the newspaper he used to take to school: the Guardian.

He began, as one did in those days, on a local paper – the Southport Visiter. But in February 1970, he was taken on by the Guardian, in those days when regional offices still survived, as number two reporter in Leeds. Here he had the good fortune to meet Eileen, who, in a kind of foretaste of a subsequent destination, was working in the local office of Air India. She became, with their marriage in 1972, his wife, best friend and constant companion, his sustainer and organiser when he needed it (organisation was not his strong suit) and a generous host to colleagues and friends.

In 1972, he moved to Belfast, where he was based through five difficult, tense and often dangerous years, alongside Simon Winchester, Simon Hoggart and Anne McHardy (who succeeded him as chief correspondent there) – frequently digging out stories, as all of them did, which the Northern Ireland Office would have preferred not to see. Later, he had a spell at Westminster, for a time as parliamentary sketchwriter, demonstrating the lightness of touch that became a hallmark. He found the work constricting but enjoyed the conviviality. He also had a spell on the Guardian news desk – frustrating, in that it did not allow him to write – and a brief spell in the features department where he wrote a column called People.

In 1983 he began a four-year appointment as the Guardian's correspondent in Brussels, where he expertly disentangled the often near-impenetrable institutions of the EU, while contriving to make his assignment sound entertaining. He greatly enjoyed, and was temperamentally wholly cut out for, the gregarious life of the foreign correspondent, with its competitive yet comradely relationships with reporters from rival newspapers developed on official occasions such as press conferences, through evenings of drinks and anecdotes and reminiscences in hotels and bars, and on hectic expeditions in pursuit of a story. But the best of his postings was as South East Asia correspondent, stationed in India, where he and Eileen were based for six years and where he displayed in abundance a quality that Paul Cheeseright, whom he got to know as an FT man in Brussels – and with whom in recent times he liked to lunch every two or three weeks in the Feathers Hotel at Ledbury – calls his "humane curiosity".

One piece widely recalled in the aftermath of his death was from March 1989, about the language used by Indian clerks, unofficially known as Hinglish: that " treasure house of archaisms, local words and the mildewed British Raj slang that makes up Indian English", where "a politician who would not dream of withdrawing a statement might decide on reflection that it was infructuous, and resile from it". Such pieces are harder to write than they look. It's too easy to sound condescending, even imperialistic. But in Derek's case the joy of the exercise came from observing and charting a collision of cultures in some ways strikingly different, yet in some ways hauntingly similar.

Derek and Eileen loved their spell in India, and sometimes thought of returning there. But in 1993 he switched to the role of Middle East correspondent, based in Jerusalem. These were less enjoyable, more constricted, times than his days in India, with the office demanding more and more stories about the peace process and with fewer and fewer chances to get out and investigate stories off the routine agenda. In 1997, the Guardian recalled him to London. He hoped for another posting abroad, but none was on offer. The thought of becoming the paper's countryside correspondent (a needful appointment in days when the London press had become increasingly metrocentric) did not appeal, though his later pattern of life showed how well he would have done it. Instead, he reinvented himself as one of a staff of nine on the Guardian's nascent website, becoming, he liked to say, the first such dedicated reporter employed on any British website.

In stories lightly seasoned with comment, he was able to draw on his whole past reporting life, writing copiously (often several pieces a day) on Ireland, Westminster, Europe, India and the Middle East, but also on other subjects he followed closely, including US politics and the war in the former Yugoslavia. His pieces on the Kosovo crisis were written with visible anguish. The website grew up around him. By the time he gave up that assignment, in 2002, the staff of Guardian Unlimited had grown to about 150.

The Browns had installed themselves in Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire, and then in Leominster, in the county that Derek most loved, and from here he continued to write once a week for the Guardian Weekly, while adding to his catalogue of enthusiasms a new taste for gardening and watching the birds in the garden. On Monday last week, though somewhat unwell, he filed a characteristic column, touching on Chris Patten's predicted BBC appointment, the emergence of a jobless generation, the failed attempt to create a New Forest Lapland theme park, and the government's indefensibly feeble response to the problems of cut-price alcohol.

On Tuesday his condition worsened; on Wednesday, he was clearly in crisis, and that afternoon, inexplicably as it seemed, he died. Because the newspaper had continued to be one of his dearest loves, he had always noted the anniversary of the day he joined the Guardian and the day he officially left it. The second of these was the Tuesday when it began to seem that his illness was serious; the first was the day that he died.

He is survived by Eileen and by his mother Renée, now 94, sister Sylvia and brother David.

Peter Preston writes: Derek Brown was (and will always remain in the memory of those who knew him) a brilliant journalist. Brilliant in Northern Ireland at the depth of the Troubles: brilliant in Jerusalem and Delhi: a brilliant observer and writer about politics from Westminster and Brussels: and, back at the Guardian ranch, a brilliantly efficient, companionable figure on the news desk. Maybe, in a way, he was so brilliant at everything, that he kept being shuffled from job to job, rather than admired for what he was where he was. It wasn't just his courage that made him so wonderful in Belfast: it was his judgment (even for a reporter in his 20s). It wasn't just his daring in the heat of the Middle East that made him so terrific there: it was the way both sides respected him, because they knew he was his own man, the straightest of arrows.

Do personal qualities come into any assessment of his life and reporting times? Of course. Derek, rotund, almost unfailingly good humoured, utterly professional whenever deadlines had to be met, was cherished because of what he was as well as because of what he wrote. He was Gaston Le Brun – Peter Cole's coinage as news editor – for a generation of Guardian reporters. And Eileen, his wife, who gave up her own career to be with him day by day, was revered in just the same way, two good companions, not one. I'm thinking of her now, because I can imagine her loss. That's because her loss is the Guardian's loss, too.

• Derek Brown, journalist, born 7 May 1947; died 23 February 2011