Finding out you have cancer is never good news: but in the “hierarchy” of malignant disease, lung cancer is one of the hardest to diagnose, one of the trickiest to treat, and one that tends to have a poor prognosis.

At the same time, though, the outlook for patients with lung cancer is improving with the advent of new drugs. What’s more, interventions in some areas of the country have shown that a few relatively easy and cheap measures can improve the rates of earlier diagnosis. As with all cancers, early diagnosis is key to successful treatment.

These sentiments were expressed at a recent Guardian roundtable, sponsored by the pharmaceutical company Bristol-Myers Squibb, that looked into how outcomes for lung-cancer victims could be improved.

The challenge now, doctors and stakeholders attending the discussion agreed, was to encourage people with any suspicious symptoms to visit their GP, and to ensure that GPs referred them for more tests. “This is a curable cancer if it’s caught early enough,” stressed Riyaz Shah, consultant medical oncologist at Kent Oncology Centre.

There’s also a revolution going on in treatment for patients with terminal illness: they are living longer than ever before. I have patients attending my clinic who were diagnosed three, four, even five years ago.”

Among the barriers to early diagnosis, the roundtable heard, was the fact that the symptoms of lung cancer were often vague and unspecific. Tom Newsom-Davis, consultant medical oncologist at Chelsea and Westminster hospital, said even where patients had thoracic symptoms they sometimes didn’t think they were dangerous. Other patients said they had been unable to get to see their usual GP or that they couldn’t get an appointment.

High mortality rate

The unfortunate fact at the present time, said consultant chest physician Dr Mat Callister of Leeds teaching hospitals NHS trust, was that one third of patients with lung cancer die within 90 days of being diagnosed. But there were indications that things didn’t have to be this way.

In some other European countries, Sweden especially, survival rates were considerably better than in the UK: the one-year survival rate in Sweden is 46%, compared with just 30% in the UK. A major difference in Sweden, said Dr Mick Peake, clinical lead at Public Health England, was that people were able to bypass primary caregivers and self-refer to chest consultants.

Worries that GPs are missing chances to diagnose lung cancer were voiced around the table – and this was ahead of research published a few days later in the British Medical Journal, which found patients who died had visited their GP an average of five times in the months before diagnosis.

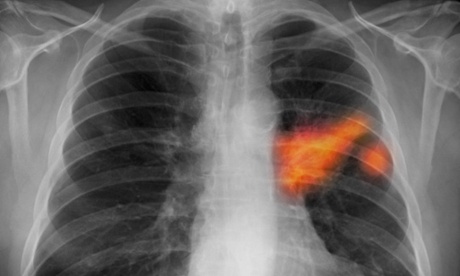

Callister said his early intervention strategy in Leeds focused on consultants like him going out into the community to encourage GPs to refer patients. The strategy had worked: across a three-year period, there had been a two-thirds increase in the number of GP-ordered chest X-rays.

Detailed results of the initiative have not yet been published but, he said, they were likely to show an increase in survival rates, and a drop in the proportion of patients whose lung cancer is not diagnosed until they present at an emergency clinic such as A&E: currently, that figure nationally is at a shocking four in 10 of all cases.

As well as encouraging GPs to refer more patients for chest X-rays, patients in Leeds were given the right to refer themselves for one. “That had a big effect on GPs’ behaviour; it’s basically saying to them, we don’t mind how many people you refer for chest X-rays; and to prove it, we’ll even allow patients to refer themselves. What GPs needed was permission to refer a lot more patients for X-rays, and that’s what we saw happening,” said Callister.

One major problem with lung cancer is that symptoms tend to be very non-specific. Making this clear to GPs had been another important part of the initiative’s strategy. Callister said:

The fact is that chest X-rays are cheap, and the radiation is a very low dose. The message we wanted to get across is: if there’s even a low-level suspicion, send them for a chest X-ray.”

Lung cancer screening

The obvious next question for the roundtable was: would it be a good idea to introduce screening for lung cancer? In general participants thought the idea had merit, although there were worries about the practicalities. “The evidence that screening is effective is overwhelming,” said Peake.

One study showed a 20% fall in mortality, and in our view it underestimates the effect of screening. We ought to implement it tomorrow and for every day that goes by lives are being lost.”

Penny Woods, chief executive of the British Lung Foundation, said patients were constantly asking why no screening programme was yet in operation, especially those who know they are at high risk.

Sara Hiom, director of early diagnosis at Cancer Research UK, said a screening programme would have benefits beyond the actual identifying of patients: as with the breast screening programme, it would focus attention on the disease and bring it out into the open. “It could bring more recognition and understanding,” she said.

But screening should only be done on the back of a clear evidence base, said Newsom-Davis. “For a variety of statistical and other reasons, demonstrating clearly that a screening programme saves lives is very difficult,” he said. One example was that people in higher socio-economic groups tended to take up screening opportunities, but lung cancer is more prevalent among lower socio-economic groups.

Shah explained that screening was likely to identify a large number of people who had nodules on their lungs that were benign. There was also a problem about how to treat early cancers detected through screening: surgery is the preferred method for treating early cancers but, said Shah, the lungs were a lot less accessible to surgeons than, say, the breast.

And also, many patients found to have lung cancer might not be good candidates – because of their age or overall health profile – to withstand surgery. But the health service had learned a great deal from the existing screening programmes, said Hiom. “The more we can screen people at highest risk the better we can target those who will most benefit,” she said.

Patient guilt

One of the saddest aspects of lung cancer, the roundtable heard, was that many patients who were diagnosed with it felt not only hopeless, but guilty about having “brought it on themselves” by smoking. Woods said:

One newly diagnosed patient told me: ‘I’ve been given a death sentence, but it’s my own fault. I didn’t realise why my cough was getting worse, and neither did my GP. But anyway, I don’t deserve to be treated because I brought this on myself.’”

This perception – that lung cancer patients have only got themselves to blame – was widespread and unfair, the roundtable was told. Many other cancers have lifestyle elements, but only lung cancer tends to be seen as self-inflicted.

Lorraine Dallas of the Roy Castle Lung Cancer Foundation said some cancers brought moral support, and others didn’t. “One patient I heard about told her friends she had breast cancer rather than lung cancer, because breast cancer was so much more acceptable and less judged,” she said.

Sally Moore of the Royal Marsden NHS foundation trust said she had researched the way lung cancer was portrayed in the media, and associations with death around it were very strong. The messages needed to be disentangled, she said.

Rosie Loftus of Macmillan Cancer Support said the nihilism associated with lung cancer was more of a feature among patients and the public than professionals. Philippa Jones of the UK Oncology Nursing Society said people needed to be encouraged to find the positives, including improving outcomes and better diagnosis. “What we need is a Kylie moment”, said Newsom-Davis, referring to how breast cancer became a mainstream issue after the singer was diagnosed with the disease.

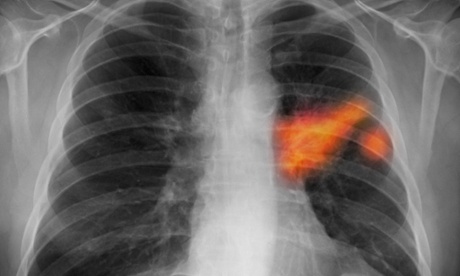

Shah said there were many good news stories, and they needed to be highlighted. “There are some amazing drugs out there, and more treatments coming through. I can show you scans that are jaw-dropping: we really are making a difference to many patients,” he said.

In focus

- Lung cancer’s vague symptoms mean it’s hard to diagnose early. Partly because of this it’s difficult to treat, and has a poor prognosis.

- At the moment, 39% of patients are diagnosed in emergency settings, such as A&E.

- Lung cancer is widely regarded as a patient’s “own fault” if they smoked. This is unfortunate as other cancers are also influenced by lifestyle, and it militates against patients seeking early diagnosis.

- But there is good news: relatively simple, and cheap, interventions can help patients get diagnosed at an earlier stage.

- There are also new drugs becoming available which can transform the outlook for patients, some of whom now live for several years following diagnosis

At the table

Denis Campbell, senior health correspondent, the Guardian

Philippa Jones, adviser, UK Oncology Nursing Society

Mick Peake, clinical lead, Public Health England

Naomi Horne, committee member, National Lung Cancer Forum for Nurses

Penny Woods, chief executive, British Lung Foundation

Riyaz Shah, consultant medical oncologist, Kent Oncology Centre

Sally Moore, nursing research fellow, the Royal Marsden NHS foundation trust

Lorraine Dallas, director of information and support, the Roy Castle Lung Cancer Foundation

Rosie Loftus, joint chief medical officer and GP, Macmillian Cancer Support

Tom Newsom-Davis, consultant medical oncologist, Chelsea and Westminster hospital

Mat Callister, consultant chest physician, Leeds teaching hospitals NHS trust

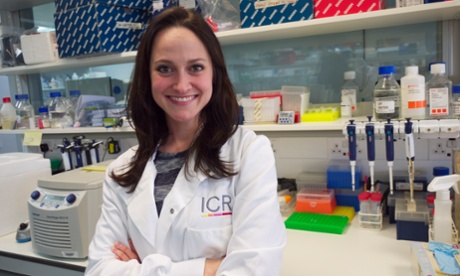

Sara Hiom, director of early diagnosis, Cancer Research UK

This content has been sponsored by Bristol-Myers Squibb (whose brand it displays). All content is editorially independent. Contact Matt Nathan on 020 3353 2841 (matt.nathan@theguardian.com). For information on roundtables visit: theguardian.com/sponsored-content