As a machine-tooled vehicle for Mel Gibson’s directorial comeback, Hacksaw Ridge couldn’t be more perfect. A study of a second world war conscientious objector who demonstrated extreme bravery under enemy fire (and won the Medal of Honor), the film allows Gibson to identify himself with a tough guy of considerable moral virtue, someone who has gone through through their own modern Calvary, taken the punishment, and come through the other side relatively unscathed. And the foundation for all this? An unswerving commitment to a little-understood corner of the Christian faith (in this case, Seventh Day Adventism), which triggers – in order – bafflement, ridicule, and finally respect.

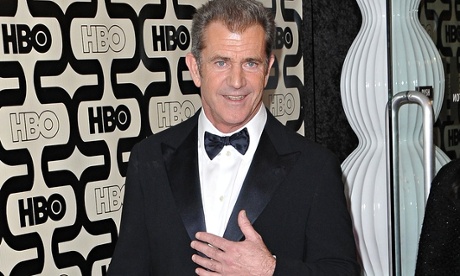

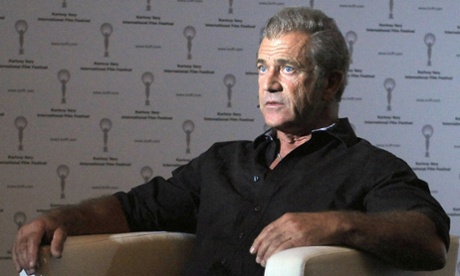

That, presumably, is how Gibson see his own journey, which began its descent after the volley of abuse he aimed at cops in 2006 after being stopped for drink driving. That year saw the release of Apocalypto, his Mayan-language thriller; it’s taken him a decade of public humiliation, frequent apologies, and occasional forays as an actor, to get to the position where he can release another film he’s directed. And as repellent a figure as many may still find Gibson, I have to report he’s absolutely hit Hacksaw Ridge out of the park.

Mostly it’s due to the film’s extraordinary second half, in which the protagonist – US army medic Desmond Doss – takes part in the assault on Okinawa. the bloody battle in 1945 for the islands just south of Japan itself, when the war in the Pacific was entering its own dying frenzy. Gibson’s gift as a director has always been the coruscating portrayal of violent combat, imparting the viscera-knotting energy of a slasher film to the conventional matrix of the sober war film. It’s not possible to say if Hacksaw Ridge contains the most violent or gruesome combat scenes ever filmed, but let’s just say it resembles Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers without any of the satire or audience-winking.

Thus Doss (played with an unlined forehead and semi-vacant grin by Andrew Garfield) must scramble over piles of mutilated corpses, exploded skulls, and screaming wounded as he carries out his heroic deeds; though Gibson employs a battery of cinematic shock tactics and impact-maximising moves, there’s no sense that he is going overboard, or straying into exploitation territory. Though the chaos, Gibson is also able to keep the action lucid and clear, even when men are going down like ninepins.

Gibson takes the story back to Doss’ childhood and teenage years in smalltown Virginia; this passage, which takes up the film’s first half, is more obviously conventional, with Doss grappling with an angry father (Hugo Weaving), romancing his sweetheart (Teresa Palmer), and bonding with his camp mates as he undergoes basic training. (Vince Vaughn considerably enlivens proceedings as the unit’s sergeant, his natural wit taking the edge off the by-now-traditional bunkhouse sadism.) It’s during this first brush with the army that Doss’s story – and Gibson’s film – takes its distinctive turn: after harrassment and a court-martial due to his refusal to bear arms, Doss is allowed to return to his unit as a medic, and join the combat mission.

Gibson, though, is smart enough to have his film play clearly to the US’s powerful religious audience: Gibson has Doss ostentatiously into combat, and gives him a brief moment of rapture-style levitation as he is being winched to safety. (One can’t help but wonder how the same audience will process Doss’ anti-gun beliefs, and his use of the constitution to defend his refusal to fight.)

Be that as it may, Gibson is a man looking for redemption, and in this redemptive vision he may just have found it.