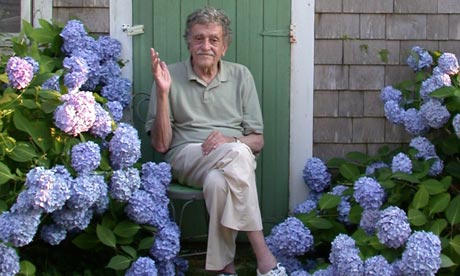

'If i should ever die, God forbid, I hope you will say "Kurt is up in Heaven now." That's my favourite joke.'

Jokes and death - and specifically jokes about death - are perhaps the simplest way of summing up the life and work of Kurt Vonnegut Jr, who died last Wednesday at the age of 84, some weeks after suffering a fall. The truth is necessarily more complex, but Vonnegut was a writer whose insistence on straight-talking - despite the superficial tricks and elaborations of his novels - became a central credo, a way of registering his anger and bewilderment at the harm visited upon innocents by nations, governments and corporations seeking to shore up their power through obfuscation and cant. If one of his aims was to provide a voice for those innocents, his method of making himself heard was both courageous and effective; he told us the hardest of truths, but in the gentlest, funniest and most amiable way he knew how. He was, to use his own word, a 'sap'.

But he was a sap who had seen and survived dreadful events. In 1944, just a few months after his mother had committed suicide, he was taken prisoner during the Battle of the Bulge, where he was serving with the 106th Infantry Division of the US army. He was sent to Dresden and put to work in a factory that manufactured vitamins for pregnant women, and there he stayed until the Allies bombed the city in February 1945. Vonnegut escaped death by hiding in an underground meatlocker; when he emerged, he and his fellow prisoners were set to the hideous task of disinterring innumerable corpses from the devastation. It was, he later remarked with characteristic irony, an irony that dares us to be appalled by mere words in the face of truly appalling suffering, 'a terribly elaborate Easter egg hunt'.

It was also to provide him with the basis for his most celebrated novel, Slaughterhouse-Five, which appeared almost 25 years later and contained the phrase that became most closely associated with him and that could most fittingly serve as his epitaph: 'So it goes.' The words recur throughout the book each time a death is recorded and what they imply lies at the centre of any understanding of Vonnegut's work: fatalism, stoicism and the acceptance that no use will come of shrinking away when the worst has happened. Questioned repeatedly over the decades about whether he thought Dresden should have been bombed, Vonnegut's most significant response was that it had been bombed; the question for him was how one behaved after that.

Slaughterhouse-Five, whose alternative title is 'The Children's Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death', rejects a conventional narrative, presenting its episodes in deliberately jumbled and fragmentary fashion and introducing the perspective of the inhabitants of the planet Tralfamadore, for whom time is not linear; our ability to properly apprehend events such as Dresden, Vonnegut suggests, is hampered rather than enhanced by our insistence on placing them in a historical framework.

Vonnegut's influence was not confined to Slaughterhouse-Five, nor to his at times uneven attempts to weave elements of science fiction into mainstream novel-writing, as he also did in works such as Cat's Cradle (1963), his favourite of his own novels, and Breakfast of Champions (1973). He presented us with a determinedly humane, cheerfully pessimistic and fearfully optimistic vision of American society as seen by an outsider; by a man whose family had emigrated from Germany in the middle of the 19th century and whose fortunes, both financial and emotional, had been shaped by the best aspirations and worst excesses of the American dream. He could not have been less precious about his writing, even creating a fictional alter ego, science-fiction hack Kilgore Trout, whose prodigious output was doomed by his incompetent choice of a pornographer as a publisher. 'What is it about blow jobs and golf?' is Trout's bemused comment on the American national character.

Writing, Vonnegut said when reminiscing about his career as a youthful journalist, was just something he found he could do easily; and when he looked back at his books, he couldn't quite imagine how. In the late-life columns he wrote for the magazine In These Times, many of which were collected in his last book, A Man Without A Country: A Memoir of Life in George W Bush's America (2006), he sounded a cautionary note to the younger generation: 'If you really want to hurt your parents, and you don't have the nerve to be a homosexual, the least you can do is go into the arts.' It seems unlikely that Vonnegut wished to cause anyone hurt, nor that he lacked nerve, and he went into the arts with a bang. Now he leaves them. But certainly not with a whimper.

Vonnegut: 'Our Voltaire'

He said: 'I think novels that leave out technology misrepresent life as badly as the Victorians misrepresented life by leaving out sex.'

A Man Without a Country

'New knowledge is the most valuable commodity on earth. The more truth we have to work with, the richer we become.'

Breakfast of Champions

'My motives are political. I agree with Stalin and Hitler and Mussolini that the writer should serve his society. Mainly, I think they should be - and biologically have to be - agents of change.'

Playboy magazine

They said:

Graham Greene: 'One of the best living American writers.'

Michael Crichton: 'He writes about the most excruciatingly painful things. His novels have attacked our deepest fears of automation and the bomb, our deepest political guilts, our fiercest hatreds and loves. Nobody else writes books on these subjects; they are inaccessible to normal novelistic approaches.'

John Irving: 'He is our strongest writer, the most stubbornly imaginative. He is not anybody else, or even a version of anybody else, and he is a writer with a cause.'

Tom Wolfe: 'As a writer, I guess he's the closest thing we had to a Voltaire. He could be extremely funny, but there was a vein of iron always underneath it, which made him quite remarkable.'

Jay McInerney: 'He is a satirist with a heart, a moralist with a whoopee cushion.'

Gore Vidal: 'He was imaginative; our generation of writers didn't go in for imagination very much. Literary realism was the general style. Those of us who came out of the war in the 1940s made it sort of the official American prose, and it was often a bit on the dull side. Kurt was never dull.'