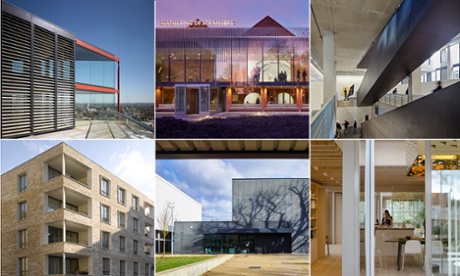

Some of the most expensive luxury flats in London will go head to head with a social housing scheme in the same city, in the race to win the Stirling prize for best building of the year, on a shortlist that reflects the vivid extremes of the UK’s desperate housing crisis.

The sharply sculpted glass towers of Neo Bankside, by Lord Richard Rogers’ practice, RSH+P, teeter above Tate Modern on the South Bank as a symbol of the capital’s superheated housing market, with penthouses on sale for up to £22m. Further east, off Cable Street, stands an unassuming block of flats by Níall McLaughlin, which completes a Peabody estate from the 1870s with a handsome brick building, blending in so well with its context you might not even notice it had arrived.

Representing polar opposites of the housing spectrum, both projects are deemed potentially worthy of having made “the biggest contribution to the evolution of architecture” this year. They are joined in the battle for the RIBA’s top gong by a cancer care centre in Lanarkshire, a south London state school, a university block in Greenwich and an extension to the Whitworth Art Gallery in Manchester.

It is a fairly subdued shortlist compared to previous years, with no stand-out flashy baubles. The projects favour a quieter approach, exuding quality and attention to detail in the way they are made. There’s a certain nostalgia in the air too, with a return to brick and precast concrete panels, and a restraint that perhaps reflects the chastened times in which they were designed – the slow trudge of the building cycle running several years behind the economy.

There are some notable omissions here, though, from Haworth Tompkins’ careful refurbishment and extension of the National Theatre to Architecture 00’s exemplary Foundry office building in Vauxhall. It would have been nice to see a touch of magic on the list too, like the Rothschilds’ beguiling Flint House, by Skene Catling de la Peña, or the elegant origami-like swimming pool pavilion by Duggan Morris for an Alfriston special needs school, both of which show what architecture can bring over and above practical needs.

Of all the candidates, McLaughlin’s housing scheme is as close to a perfect answer to its brief as any. As a model for other housing associations and local authorities to follow, awarding it the prize would send out a powerful message about where thoughtful architecture is most needed right now.

The shortlist

Burntwood School, Wandsworth, SW17

Allford Hall Monaghan Morris

Odds: 8/1

A welcome timewarp, this £40m secondary school complex in south London takes its cue from the 1960s campus that stood on the site, originally built under the direction of Leslie Martin (whose assembly block remains) and the architects’ department of the Greater London Council. With six new teaching blocks in a parklike setting, it is a striking throwback to the days when school buildings were invested with love and care, flooded with light and built to last.

As one of the last schools of new Labour’s costly Building Schools for the Future programme, the design represents a culmination of the architects’ 10-year involvement with contractor Lend Lease, and it has a maturity that marks it out from many of the earlier BSF projects. It sheds the usual quirks of jauntily coloured plastic facades and endless break-out zones, concentrating instead on generous classrooms, wide corridors and big windows. It is a strong, grown-up building, with the air of a university campus, which the teachers say has had a knock-on effect on the pupils’ behaviour.

Rare for a school, it’s also beautiful. The sculpted concrete facades have already inspired GCSE art projects; their chamfered precast panels could be straight from the studio of Marcel Breuer, the Bauhaus designer who built a similar school in Boston in the 1970s. It also helped that the headteacher was a fan of Mies van der Rohe – an influence evident in the sleek covered walkway, ingeniously fashioned from off-the-peg bus-stops.

It might not win, but it’s a useful reminder of all the learning that’s now been lost, since the last government handed the task of school building over to manufacturers of out-of-town sheds.

Darbishire Place, E1

Níall McLaughlin Architects

Odds: 3/1

Another project that takes inspiration from what was already there, this quiet brick block of 13 flats completes the Peabody estate in Whitechapel, which was originally built by the housing association’s chief architect, Henry Darbishire, in the 1870s. Filling in the gap of a second world war bomb site, the building follows the sobriety of Darbishire’s designs for “cheap, cleanly, well drained and healthful dwellings for the poor”, but updates it with generous internal spaces and sharply-crafted details that make it as near to a model housing scheme as you could find.

It is the work of London-based Irish architect Níall McLaughlin (previously Stirling prize shortlisted in 2013 for a beautiful stone chapel), who produced 35 feasibility studies for Peabody infill sites before being commissioned for this scheme, amassing a level of understanding that suffuses every aspect of the building.

Clever planning means that all but the smallest flats are triple-aspect and each unit has its own big outdoor terrace, deeply recessed to give a sense of privacy, while allowing parents to keep a watchful eye on the playground below. Like a stack of backyards, these patios provide crucial space for the domestic flotsam of bikes, plants and drying racks.

There are humanising touches everywhere: little lobbies mean you don’t enter straight into the flats, while the main staircases have a meandering generosity and an elegant curving sweep, rather than the usual straight-up flight.

Built of biscuity brickwork, to match the creamy Cambridge gault clay of the Darbishire blocks, the facades have deep window reveals (another lesson taken from the Victorian architect) to reflect more light into the flats and give a quality lacking in most flimsy contemporary apartment blocks. It is a particularly impressive achievement within the tight budget of £1,870/sqm.

One of the finest results of Peabody’s recent work, under the leadership of Claire Bennie until this year, it is eminently worthy of the Stirling prize.

Maggie’s Lanarkshire

Reiach and Hall Architects

Odds: 6/4

An admission: this is the one project on the list I haven’t yet seen in the flesh. The 12th building in the programme of cancer care centres, begun by architecture critic Charles Jencks and his late wife Maggie in 1995, it is notably less showy than many of the centres before, such as Frank Gehry’s crumpled canopy in Dundee or Zaha Hadid’s bunker in Fife. The programme has been criticised for procuring boutique architectural baubles by famous names, but this £1.8m Lanarkshire outpost is more down-to-earth than its predecessors, designed with creating a calming, domestic environment in mind.

The work of Edinburgh-based practice Reiach and Hall, who have considerable experience designing hospital environments, it is a simple single-storey building arranged around small courtyards (or “sitooteries”), with a long glazed wall that gives on to an expansive garden. The emphasis on outdoor space is intended to attract more men to use the centre – doing a spot of gardening proving a less confrontational setting for conversation than a counselling room.

The whole thing is encircled by a buttery brick wall, with odd bricks missing to make a random perforated pattern, reminiscent of the punch cards used to program early computers, that casts dappled light over the site. With timber-lined interiors and the courtyards topped with gold “suncatcher” crowns, the complex has the sleek air of a Californian Case Study House, filtered through a Lanarkshire lens.

It’s a finely crafted thing, but wouldn’t it be nice to see a full-scale hospital on the Stirling shortlist for a change?

NEO Bankside, SE1

Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

Odds: 6/1

If Richard Rogers’ buildings are often likened to cheerful Meccano sets, with their exposed steel bracing and celebration of bolts, this £400m apartment complex – which rises behind Tate Modern – is the executive desk toy version you’d buy in Harrods.

Its 200 flats, which are on the market for up to £22m, have the finish you should expect for such a price-tag, and every detail has been meticulously engineered. The exposed structural fetish has even been elevated to a luxury commodity, with customers paying a premium for apartments with the giant steel nodes outside their windows. Still, it doesn’t really make for nice homes – the penthouse feels like the departure lounge of a small regional airport.

The project is the work of RSH+P partner Graham Stirk, who was also responsible for the luxury ghost town of One Hyde Park and the lavish Riverlight scheme in Nine Elms, and it takes a similarly anti-urban approach that shows little understanding of its London context. It would be more at home in the gated compounds of Singapore.

The five hexagonal “pavilions” stand above a bleak sliver of manicured garden – which is open to the public by day, but clearly designed to discourage lingering – while the towers loom over the neighbouring 18th-century almshouse, bulging out of their bracing like a herd of overweight bankers swaggering through the neighbourhood.

If its physical heft wasn’t offensive enough, a look at the project’s planning history should be a wakeup call. While the borough’s policy requires 40% affordable housing, the developer, Native Land, agreed to provide just 27.5%, with all social-rented units built off-site in a cheaper area (which have yet to all be built). It justified this in its viability assessment (PDF) on the basis that average sales values would only be £754/sqft. In reality, the flats sold for an average of £1,326/sqft (PDF).

It may be well made, but this is the kind of project that is only helping to destroy the social fabric of London. It is not something to be celebrated with an award.

University of Greenwich Stockwell Street Building, SE10

Heneghan Peng architects

Odds: 8/1

Architecture isn’t often taught in inspiring spaces, but Greenwich University has decided to change that. After being housed in a tower block in Woolwich, an old college in Dartford, and a Victorian tycoon’s mansion in Eltham, its department of architecture has moved into a purpose-built new facility in the heart of the Unesco World Heritage-listed maritime centre of Greenwich, together with the departments of landscape, arts and the main university library.

It is a vast building, cleverly shoehorned into a tight site by Irish architects Heneghan Peng, whose small office is used to tackling projects of an unlikely scale and international scope – from the gargantuan Grand Egyptian Museum being built near the pyramids of Giza, to the Palestine Museum under construction in the West Bank, and the Stirling prize-shortlisted Giant’s Causeway visitor centre.

Their buildings often have a geological feel, as if hewn from the landscape, and even in Greenwich, they have brought their tectonic sensibility. Like a big block of stone that’s been cleft open with glazed canyons, the building brings natural light deep into its centre.

Inside, the studios have a lofty scale and a strong palette of raw materials, with concrete, steel and exposed services giving an industrial air. Life revolves around the hallowed “crit pit”, where students’ presentations take place – a 10m-high space styled like a dojo, with an elevated viewing gallery adding a theatrical touch. A series of roof terraces provide space for experimental allotments and a bubbling algae farm, plus spectacular views across the Greenwich rooftops.

It could have been a great building but, from the outside, its power has been compromised by the pressures of its heritage setting. The bold design of dynamic thrusting blocks was watered down, following guidance that it was “not traditional enough” yet also “not bold enough” – deemed too radical by some local residents, too unadventurous by others. The result feels insipid, as if trying too hard to please all parties.

The Whitworth, Manchester

MUMA

Odds: 3/1

When the Whitworth Museum first unveiled its collection in July 1890, the art critic of the then Manchester Guardian scoffed with disbelief. It was “almost ludicrously bad,” he said, affording “little or no ground for hope” for the future of the museum, which would likely be “choked with rubbish” forevermore.

How wrong he was. Under the visionary leadership of Maria Balshaw, the institution has earned a name as a vibrant bastion of contemporary art. Following a £15m extension and refurbishment of its rambling Victorian building, it was recently crowned Museum of the Year. Might it also steal the Stirling prize? It’s certainly a likely contender.

The work of Glasgow-trained London-based architects MUMA, who brought their skills to bear on the V&A’s medieval and renaissance wing, the project breathes new life into what had become a dingy muddle of galleries. With two new wings extending into the neighbouring park, the building finally embraces the asset on which it had turned its back for generations, with long glass walls providing alluring glimpses of the artwork inside. A glazed pier-like cafe provides a magical spot to have a coffee suspended among the trees.

Low ceilings from the 1960s have been mercifully stripped out to reveal soaring vaulted halls, while new archive storage and educational spaces have been intelligently carved out. Care has been invested in details, from the triangular, polished stainless-steel window mullions, designed to dissolve into the view of the park, to a huge openable facade for oversized deliveries and a freight lift that can hold an entire class of children.

But perhaps the building’s biggest contribution to architecture is invisible. Revising the received wisdom of the correct environmental standards to display art, the environmental strategy, developed with Buro Happold, adopts a revolutionary passive-first approach, meaning the temperature and humidity is controlled without the need for the usual mechanical paraphernalia. In terms of breaking new ground, that could well be its most important legacy.

• This article was amended on 17 July 2015. An earlier version of the entry on Maggie’s, Lanarkshire, referred to a computer programme, rather than program. The latter is Guardian style.