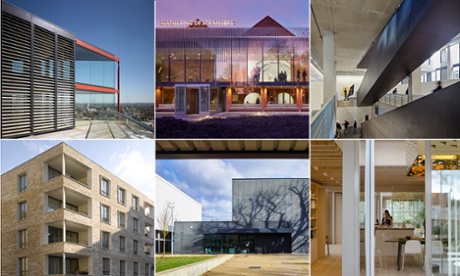

After years of being occupied by the usual big-hitters, this year's RIBA Stirling prize shortlist for the best building of the year is refreshing for its wave of new names – five of the six practices grace the list for the first time, and half have women at the helm.

The favourite to win is an exceptionally crafted stone chapel, by Niall McLaughlin, for a theological college in rural Oxfordshire – perhaps a dream commission in an area of beauty that is hard to match. The Giant's Causeway visitor centre enjoys a similarly pristine context of rolling fields, carving a cleft in the landscape with a bold piece of land-architecture that limbos beneath the planners' radar.

A second Irish practice, Grafton, makes the list with a new medical school and student accommodation blocks for Limerick University. With strongly sculpted spaces and a keen awareness of their civic role, the buildings raise the bar for facilities of their kind – which too often end up as ill-considered boxes.

Elsewhere, the grittier contexts of postwar council estate refurbishment and suburban homes in Essex bring the present housing crisis into sharp focus. The regeneration of Sheffield's maligned Park Hill estate has divided critics with its brash colour palette, but it shows an intelligent reworking of an ailing megastructure that could be transferred elsewhere.

Alison Brooks – joint winner of the 2008 Stirling prize for the Accordia housing in Cambridge – has attempted to reinvent the suburban house type in Harlow, with buildings of an interior generosity unmatched by volume builders. But the compromise is felt outside, where it all seems a bit tight.

A house of a more stately kind can be found in the fortified manor of Astley Castle, subject to a sensitive exercise in transformative restoration by Witherford Watson Mann, whose confident intervention goes beyond mere conservation – although perhaps much of the evocative power could be said to lie in what was already there.

Reflecting the fact that small practices often devote more energy and time to the craft of detail, the big offices of such knighted worthies as David Chipperfield and Zaha Hadid failed to make the grade. Nor did promising arts projects pass muster: both the MAC in Belfast and the Jerwood Gallery in Hastings missed out, while none of the schools made the list – perhaps a telling barometer for the current value we now place on arts and education.

In an exceptionally strong year, the decision is likely to come down to a choice between the pristine architect's architecture of McLaughlin's chapel, and the intelligent pragmatism of Brooks's housing, both of which benefited from unusually enlightened clients. My choice would be for an unlikely outsider in the form of Grafton's campus, a scheme that shows architecture's power of place-making beyond the singular building alone.

The shortlist (odds provided by William Hill)

Newhall Be, Alison Brooks Architects (3/1)

Judged against the quality of current volume house-building, Alison Brooks's streets of 84 faceted timber houses in Harlow are something of a miracle. Ditching the standard long and thin house plot of 5x20m, Brooks opted for a 10x10m plot, creating a T-shaped plan with courtyards at ground and first floor. This allows for an unusually generous open hall and staircase, as well as a dedicated ground-floor home office – attempting to change the suburban street from a desolate place into a little working community of "shopfronts". Prefab timber cassette construction, rather than traditional trusses, also means the roof space can be used, either as lofty cathedral ceiling or an additional bedroom.

But such features come at a cost. To justify this internal generosity, the houses are jam-packed like sardines into narrow streets – which are now choked with cars, due to lack of parking, somewhat destroying the idea of a social streetlife.

Park Hill, Hawkins\Brown with Studio Egret West (9/1)

The Marmite project of the bunch, Park Hill has been loved and loathed in equal measure since it opened in 1961, standing as a brutalist concrete cliff-face on the hills above Sheffield. 50 years later, its refurbishment by Urban Splash has proved no less divisive. The subtle brick palette, which graduated from chocolate to mustard, has been replaced by loud tutti-frutti panels of eye-searing citrus shades, flattening the facade into a garish billboard of gentrification – a symbol of this public–private asset transfer.

But closer inspection reveals some clever moves. The flats have been intelligently reconfigured, providing windows on to the "streets in the sky", a feature the building's original architect always regretted omitting. The amount of glazing has been doubled, and circulation fixed with thrilling glass lifts and a spiralling corkscrew escape stair. It could be a model for estate regeneration – if councils had the confidence to do it themselves.

University of Limerick Medical School and student housing, Grafton Architects (6/1)

In a hotchpotch university campus of disappointing sheds, Grafton's carefully composed ensemble of buildings shows how considered architecture can create a powerful sense of place – on a very tight budget of €1,220 per sq m. The trio of student accommodation blocks avoid the usual form of flimsy stacked hutches, instead standing as a cluster of supersized houses, with canted rooflines and big openings deeply carved into brick walls.

Faced in blue-grey limestone, the medical school stands as a formal anchor, fronted with a grand double-height colonnade and opening up inside to a top-lit atrium – off which teaching and study areas are designed as rich theatrical spaces on an almost heroic scale. The buildings also have a generous attitude to the surrounding public space: open undercrofts provide routes through the campus, while deep thresholds make welcoming places to pause and gather. From joinery details to urban form, it feels every element has been meticulously considered.

Giant's Causeway Visitor Centre, Heneghan Peng architects (3/1)

Bursting out of the rolling hills on the coast of Northern Ireland, the Giant's Causeway visitor centre ruptures from the ground, as if formed by a great slippage of tectonic plates. Prising the landscape open to reveal dark stone fissures, the building hunkers down low, almost invisible from most directions. Conceived like a piece of land art, visitors are invited to walk up a grassy cleft between the building and its sunken car park, and climb on to its roof, where skylights illuminate a cave-like world of raw concrete below.

Perfectly judged, the project strikes the difficult balance of being a powerful geological presence in its own right, without upstaging the Unesco world heritage site of basalt columns that lies beyond. Its evocative interior balances the demands of a busy cafe and shop – only let down by a disastrous interpretation display, by other less able hands.

Bishop Edward King Chapel, Niall McLaughlin Architects (9/4)

The bookies' favourite, Niall McLaughlin's chapel for Ripon theological college in Cuddesdon, Oxfordshire, is the kind of building every architect dreams of making. A jewel-like distillation of ideas about materials, light and space, it is beautifully built in hand-cut Clipsham limestone – one of the many benefits of its £2m budget.

An elliptical drum that appears to be half floating boat, half defensive bastion, it grows from a smooth base to a rough textured facade of alternating cut and broken stone – laid to give a woven, drape-like effect – up to a continuous clerestory window. From here, heavenly light is shed into the tear-drop interior, where slender bleached timber columns rise to intersect in a criss-crossing cat's cradle of paper-thin branches above the congregation. Many a transcendental moment will no doubt be had in this space, not least thanks to the architecture – but would projects responding to tighter constraints be more worthy winners?

Astley Castle, Witherford Watson Mann Architects (6/1)

It has been home to three queens of England, functioned as a garrison during the civil war, and served as a bawdy hotel and bar – before one particularly raucous night saw the place gutted by fire in 1978. After 10 turbulent centuries, the fortified manor house of Astley Castle in Warwickshire was reborn last year as a holiday rental home for the Landmark Trust, with an impeccable intervention by Witherford Watson Mann.

Their addition is neither the usual insertion of a "look at me, I'm the modern bit" glass box, nor is it the kind of understated invisible mending so beloved of conservation architects. Knitting walls of brick and timber into the ravaged stonework, the architects have crafted a layered sequence of domestic rooms that revel in framing views and overlapping spaces, inside and out – giving the bewitching sense of a contemporary house enclosed by the jacket of the original ruin.