Few global figures were as compelling as Ariel Sharon, the former Israeli prime minister who has died aged 85. A remarkable blend of maverick and mainstay, he fought in all of Israel's main wars and gave the impression of having been involved in every political development since the nation's birth in 1948. He was left in a persistent vegetative state by a massive stroke in January 2006.

As a military officer and general, Sharon had courted international controversy by his battlefield belligerence. Historians blamed him for instigating unnecessary wars; foes accused him of targeting civilians. A considerable number wanted him tried as a war criminal for allegedly abetting atrocities against Palestinians in Beirut in 1982. His supposed passage from warmonger to peacemaker was the stuff of countless editorials.

Sharon was more than a piece of living history, however. He was also a supremely canny politician who knew the pulse of Israeli civil society better than any other. First elected premier in 2001 and re-elected in 2003, in November 2005 he did the unthinkable for a ruler: he resigned from his own party. Breaking free from the Likud – the coalition he had helped cobble together in 1973 – he created a brand new party from scratch, Kadima ("forward" in Hebrew). For most politicians, this would have been tantamount to suicide.

Still in the glow of his aura, and now under his disciple, Ehud Olmert, Kadima swept aside Labour and Likud in the March 2006 elections. Long before then, Kadima's creator had established a reputation for building up and then destroying. In August 2005 he audaciously dismantled all Jewish settlements in Gaza, in the teeth of fierce protests. Sharon personally planned these colonies – and many more in the occupied West Bank – in the mid-1970s; hence the feeling on the right that he had betrayed the Greater Land of Israel cause.

"Withdrawal" was clearly, then, more than an empty gesture. In the words of several Palestinians who had written internet messages shortly after his stroke in 2006, he had been the first Israeli leader to acknowledge in practical terms their right to owning part of the "Holy Land". His own ultimate peace plans remained a secret. But the Hamas victory in Palestinian elections only three weeks after his stroke and the 2006 war with Hezbollah in Lebanon shifted the balance yet again.

Sharon became prime minister in his twilight years on a pledge to stifle the Palestinian rebellion that began in September 2000. On 6 February 2001 he defeated the Labour incumbent, Ehud Barak, by almost 25 percentage points in Israel's last direct prime ministerial elections. On 28 January 2003 he cemented his power by leading the Likud to a historic electoral victory over its Labour rivals.

Both as general and statesman, Sharon acted like a bulldozer. Critics held him responsible for miring Israel in Lebanon from 1982 to 2000, when some 1,200 Israeli soldiers and 17,000 Lebanese died. Many also blamed him for sabotaging the 1993 Oslo peace process. On 28 September 2000 he visited Jerusalem's Temple Mount with a "message of peace" and 1,000 armed police. If it was a calculated move, it paid off. His presence prompted a full-blown Palestinian uprising, and allowed him to gain national leadership four months later by posing as Israel's saviour.

To his supporters he was always "Arik, Melech Yisrael" (King of Israel), the only politician who told it like it was. Sharon had proved his bravery during the 1948 war of independence, and reached public attention five years later, when the prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, chose the 24-year-old officer to head a new elite commando squad called Unit 101.

Their brief was to eradicate cross-border raids by Palestinian fedayeen (guerrillas), yet many felt the overzealous Sharon was becoming a law unto himself. He regarded civilians who "harboured terrorists" as legitimate targets. On 14 October 1953, his commandos attacked Qibya in Jordan and killed 69 residents, including women and children. After Qibya, concluded Egypt, peace with Israel would be impossible. Many historians feel the raid contributed to the Suez crisis three years later. It was during this latter conflict that Colonel Sharon captured the strategic Mitla Pass and thus played a key role in capturing the Sinai peninsula for Israel. After the war, though, Israel returned the Sinai to Egypt, and Sharon faced criticism for disobeying orders and recklessly endangering soldiers' lives at Mitla.

In the June 1967 six-day war, Major-General Sharon retook both the pass and Abu Agheila. In 1970-71, he crushed dissent in occupied Gaza by relocating 160,000 refugees, killing 100 Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) suspects, and arresting another 700. Witnesses recall him drawing a grid for his patrols and then bulldozing every house on it. In October 1973, he claimed he had turned the tide of the Yom Kippur war by crossing the Suez canal, trapping the Egyptian 3rd army and winning the largest tank battle since Kursk in 1943. Ever mindful of his image, he was photographed with a bloodstained bandage swathing his rakish quiff.

Sharon entered the Knesset in 1973 and became minister of defence in 1981. As soon as he was in office, he started planning to alter the regional map. Ostensibly, he aimed to eliminate threatening PLO units in southern Lebanon. In fact, he planned to install a puppet Maronite regime in Beirut and expel Lebanon's 300,000 Palestinians. He calculated that they would flee to Jordan, overthrow King Hussein and build a new Palestine on the ruins of the Hashemite kingdom. Israel would then hem in its most dangerous foe, Syria. So went the theory.

In practice, Sharon's masterstroke began to go awry soon after he launched Operation Peace for Galilee on 6 June 1982. It was rumoured that he and the chief of staff, Rafael Eitan, misled the prime minister, Menachem Begin, who envisaged a limited 48-hour operation (Begin resigned a year later). Sharon did dislodge the PLO, but at the cost of creating hundreds of thousands of refugees, risking war with Syria and bombing Beirut virtually unremittingly. For the first time, Israeli conscripts balked at fighting what Begin called a "war of choice".

Matters worsened with the assassination of Sharon's ally, the Lebanese president-elect Bachir Gemayel, on 14 September 1982. For the next three days, Phalangist Christians took revenge, under Israeli eyes, by killing between 800 and 2,000 Palestinians at the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps in Beirut. Some 400,000 Israelis marched in protest, and an Israeli commission of inquiry held Sharon personally, albeit indirectly, responsible. After much resistance, he resigned in February 1983 and was forbidden from holding the defence post again. In Lebanon, his excesses spawned a new enemy among the formerly friendly Shias of the south – Hezbollah. Over the ensuing 18 years of Israel's occupation of part of Lebanon, these fundamentalists proved more hostile than the PLO had ever been.

Colleagues had detected signs of megalomania in Sharon long before these events. He would yell obscenities at fellow officers and disobey orders in order to conduct reckless battlefield operations. Despite that, he was an educated man and a witty raconteur. He revelled in classical music, and cherished friends ranging from Israeli leftists such as Shimon Peres to African dictators such as Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo). Sharon had studied Middle East history at Jerusalem's Hebrew University in 1952, military strategy at Camberley Staff College, Surrey, in 1957, and graduated in law from Tel Aviv University in 1966.

He was born at Kfar Malal, 15 miles north-east of Tel Aviv, a moshav (collective settlement) in central Palestine. His parents, Samuel and Vera Scheinerman, had arrived six years earlier from Russia. Ariel was barely a year old when Bedouin marauders threatened their home. No doubt such family memories coloured his views, although later Arab negotiators found him neither racist nor disrespectful. He also never forgave moshav-dwellers who ostracised his parents for running a private plot.

As a teenager he fought for Labour's Haganah militia. In early adulthood, he remained within the ambit of Mapai, Labour's chief constituent party. But when he entered politics, he gravitated towards the right. In December 1973 he became a Knesset member for the capitalist Liberal party, befitting a man who was Israel's largest cattle rancher. He helped create the Likud bloc by joining his Liberals and other smaller factions to Begin's Herut as senior partner. Bored with the niceties of opposition politics, in 1975 he became security adviser to the Labour prime minister, Yitzhak Rabin, though in 1977 he contested elections as head of his own Shlomtzion (Peace of Zion) party.

Sharon was now a leading advocate for militant settlers. Although never a religious Jew – his passion for gargantuan plates of non-kosher food was legendary – he saw the settlers as Israel's new pioneers. Between 1978 and 1981, back in the Likud, he used his powers as agriculture minister to establish 240 settlements in the West Bank and Galilee. These "facts on the ground", he hoped, would render any future territorial compromise impossible.

Land was Sharon's leitmotif. But in government, realpolitik prevailed. He agreed to return Sinai to Egypt, and in April 1982 he dismantled Israeli towns there, to the chagrin of his supporters. Many of these settlers decamped to new locales in Gaza, at Sharon's instigation, only to be removed once more, 23 years later. He survived Lebanon to become industry minister in the Likud-Labour coalition governments of 1984-90, but failed to topple the Likud leader and prime minister from 1986, Yitzhak Shamir, in internal party elections.

From 1990 to 1992, Sharon (now housing minister) mischievously founded a new settlement whenever the US secretary of state James Baker visited Israel. This led an angry US administration to cancel a $10bn loan guarantee. Sharon ran up debts of $600m on grandiose immigrant housing schemes in remote locations. Wary at the mounting cost of his beliefs, voters threw out Likud in 1992 and elected Labour. Likud skipped a generation by choosing Binyamin Netanyahu, and not Sharon, as Shamir's successor. In opposition, he rejected the Oslo peace agreement as "a moral error of the first order". He had mused about meeting Yasser Arafat in the 1970s; now he called the PLO chairman a "war criminal".

Envious of Netanyahu's appeal, Sharon considered opposing him in the first direct election for prime minister in May 1996. By standing down, he avoided splitting the rightist vote and thus allowed Netanyahu to narrowly beat the prime minister Peres. Netanyahu initially excluded Sharon from his cabinet, but then grudgingly created a portfolio for him, the ministry of national infrastructure. Characteristically, Sharon exploited the office's ambiguities to become tsar of water, electricity, housing and roads. Then, in October 1998, as the newly appointed foreign minister, he astounded his acolytes by signing the Wye River agreement, facilitated in Maryland by President Bill Clinton, which granted Palestinians control over another 13% of the West Bank.

In May 1999, when Netanyahu lost national elections to Labour's Barak, Sharon was virtually the only big player left in the Likud. He assumed the party leadership and became head of the opposition. He rebuilt the shattered party, thwarted Netanyahu's attempted comeback in late 2000, and lambasted Barak's concessions to Arafat at Camp David in July 2000. Then, in elections in February the following year – at the age of 72 – he garnered 62.5% of the vote and overwhelmed Barak.

As prime minister, Sharon hoped to inspire the esprit de corps of his army years. A throwback to the early Zionists, he was wedded to the soil, certain of his beliefs, the antithesis of the supposedly pitiable diaspora Jew. The public knew him as the hero of his autobiography, Warrior (1989). Now he rejected an understanding reached between Clinton and some Israeli and Palestinian ministers. This pact to end violence and address the most pressing issues (Jerusalem, settlers, statehood and borders) was unofficially agreed at Taba in Egyptian Sinai, during late December 2000 and early January 2001.

By then the Al Aqsa intifada had been raging for three months and showed few signs of abating. Israeli voters – including Labourites disillusioned by what they saw as Palestinian mendacity and belligerency – felt drawn to the old warrior. Elected on a landslide in prime ministerial polls in February 2001, Sharon set about creating a government of national unity with a defeated Labour.

Two considerations influenced this decision: a desire not to repeat the error of ignoring national fissures, as in 1982; and a sense that a Labour cabinet presence would insulate him from international criticism. He especially welcomed Peres, reappointed Labour leader after Barak's resignation. The veteran Labourite's expertise and links with Arab and western leaders was a prized asset; he became foreign minister and deputy prime minister.

True to form, Sharon intensified retaliation against Palestinians, including "targeted assassinations". He once described Israeli retaliations as "a continuation of our war of independence". Simultaneously he hosted visiting US diplomats, first the CIA director George Tenet and then Senator George Mitchell. Yet he demanded "10 days of quiet" before talks with Palestinians could start. Palestinian militants continued suicide attacks on Israeli citizens. As long as established Palestinian leaders could not or would not stop such actions, Sharon could claim Israel had "no peace partner". By the same token – some Israeli journalists said – Sharon had undercut moderates by surrendering the trump card to extremists.

Israel's new ruler refused to meet Arafat, whom he charged with duplicity and connivance in murder. Next, he exploited US fury after 9/11 and convinced President George W Bush that Israel's fight against Hamas and Fatah militants was part of the new "global war against terror". Bloody suicide bombings in early 2002 prompted him to reoccupy Palestinian cities. Israeli troops sealed Arafat in his compound in Ramallah, but while it was impossible for the PLO chief to leave, it became increasingly perilous for Sharon to leave Israel too. At one stage it appeared that a Belgian court would charge him with war crimes.

He faced troubles at home as well. Wariness at the lack of a grand strategy eroded support, while poorer sectors balked at the austerity policies of finance minister Netanyahu. Israel's economy was ailing: poverty was increasing and a single mothers' movement gathered pace. It seemed that Sharon had momentarily lost touch with his core constituents.

In August 2002, Labour left the government in protest at secret budgetary contributions to settlements. Bereft of coalition partners, on 6 November Sharon called for early parliamentary elections. Although three weeks later he won the Likud leadership election, it seemed he risked defeat at the polls. Not only was he haunted by a scandal over alleged bribes and unethical payments dating back to 1999, but voting irregularities in choosing the Likud electoral list added to his problems. Labour's new leader, retired general Amram Mitzna, accused Sharon of acting like a mafia boss. The tide turned in his favour after new terror attacks (including one against Israeli tourists in Mombasa) and voters' wariness about Mitzna's daring peace plans. On 28 January 2003, Likud doubled its seats to 40, Labour fell to 19, and Sharon began planning a new administration.

Mitzna, meanwhile, refused to join the new coalition. Likud chose instead to ally itself to smaller parties. There were chasms over core beliefs (on peace, synagogue and state, and economic policy). Rightwing and religious parties sat uncomfortably with the moderate, secularist Shinui.

On 30 April the US released its "road map to peace". Despite his 14 objections, Sharon accepted it and committed Israel to withdraw from West Bank cities and release more Palestinian prisoners. A fortnight later, he held talks in Jerusalem for the first time with the new Palestinian prime minister, Mahmoud Abbas. Yet despair returned as June saw yet more terror attacks and Israeli reprisals, with Palestinian civilians caught in the crossfire. Some air force pilots refused to fly if innocents were endangered. There was desultory criticism from America, but Israel's principal ally was otherwise engaged in Iraq. Arafat spoilt the US grand plan by denying Abbas meaningful powers, leading to his resignation on 6 September; and an unofficial Palestinian truce began to crumble.

Sharon chose to press ahead with two unilateral measures. One was the accelerated construction of a "security fence" or "separation wall", ostensibly to stave off suicide bombers. In July he rebuffed Bush's request that he freeze the barrier construction. The second venture was to prove much more controversial. After months of tinkering with dismantling illegal hilltop settlements, while expanding better established ones, Sharon shocked the world on 2 February 2004, by saying Israel would pull troops out of Gaza and evacuate all 22 settlements in the strip.

Angry settlers galvanised half of Likud's Knesset members to deride the scheme as the end of Eretz Yisrael. On 2 May it was Sharon's turn for a shock when party members rejected his Gaza plan by a 2-1 margin. Had his political nous failed him? Leftist critics had questioned his sincerity over leaving Gaza. Yet they had to reconsider when he sacked ministers to force his cabinet to accept the plan.

In July, tens of thousands of settlers formed a 50-mile human chain to condemn the plan. Bizarrely, a large peace rally around that time hailed Sharon as a convert to compromise. Some militant settlers and their rabbinical mentors hinted that he deserved death for "treachery", just like his predecessor, Rabin. Evidently rightwingers were not assuaged by his decision to assassinate successive Hamas leaders, Sheikh Ahmed Yassin and Abdel-Aziz Rantissi. Later that year, foreign ministry staff worried that Israel was becoming an international pariah. So had the old warrior truly turned into an elder statesman? Or did he plan to use Gaza withdrawal as a ruse to cantonise Palestinians in a Jewish-dominated West Bank?

Arafat's death that November was a chance to test the theories. Publicly, Sharon acknowledged the possibility of gaining a "partner for peace". His four-decade involvement with Arafat had so dominated Israeli-Palestinian relations that until one or other, or both, players vacated the stage, said critics, there could be no peace. Sharon cautiously welcomed Abbas's selection as PLO chairman, and promised that Palestinian presidential elections would proceed.

Scarcely had this "opportunity" arisen than a budgetary quarrel smashed Sharon's minority coalition government. Peres (returned as Labour leader) again threw Sharon a lifeline; the pair negotiated a new coalition to promulgate Gaza withdrawal. Meanwhile, Abbas convincingly won the presidential polls on 9 January 2005, and met Sharon at a much-publicised summit on 8 February. Together they declared a truce in the four-year intifada, after which Sharon vowed to release another 500 Palestinian prisoners.

Sharon prevailed upon his cabinet to back Gaza withdrawal. The pullout began on 1 August, and the last settler left seven days later – ahead of schedule, notwithstanding much-publicised protests. The Israeli flag was lowered in Gaza a month later. Ultimately, Sharon ceded control of Gaza's southern Rafah border post to Egypt, another notable departure from Israel's traditionally cautious strategy. In the final analysis, Sharon calculated accurately: most Israelis then supported withdrawal as a necessary palliative on what was seen then as the road to peace; and settlers, once touted as "national pioneers", appeared out of touch.

Less successful was the hoped-for joint strategy between Abbas and Sharon. Their meeting in June 2005 ended in failure, and post-pullout meetings were cancelled after terror attacks. In what was seen as a landmark address to the United Nations, on 15 September 2005, Sharon called for peace and overtly recognised Palestinian rights, while reasserting Israel's claims over a united Jerusalem and its determination to fight terror.

It took the surprise victory of Amir Peretz over Peres in the Labour party, in November, to provide the catalyst for change. Within hours Peretz ordered Labour ministers to desert the coalition; three days later Sharon dropped his own bombshell, announcing the creation of what was to become Kadima. He cited frustration at backstabbing by Likud central committee members and parliamentary rebels. He had urgent reforms in mind, but could not enact any, he claimed. Immediately 13 Likud Knesset members joined him in exile. Some rebel Labourites followed suit, and even Peres pledged support. Opinion polls correctly suggested that Kadima would trounce Likud and Labour. Once more, Sharon, the creator of worlds, had become the destroyer and daring rebuilder, but this time he would not see the consequences.

What Kadima stood for was not clear. Some say Sharon was about to launch a New Deal to meet the challenges that Peretz was posing on behalf of the neglected poor; others felt his security toughness would provide cover for daring new peace plans. Nor did the election of his nemesis, Netanyahu, as head of what remained of Likud much trouble the old soldier.

It seemed that the appeal of Sharon, around whom the party coalesced, was sufficient to command trust in Kadima. Hence when he suffered a first, minor, stroke, in December 2005, a few began to realise the danger of placing their faith in his personality-driven enterprise. A second stroke, a few weeks later, cast all of Israeli politics into doubt. It fell to Sharon's ally, Olmert, to assume the role of acting prime minister. Olmert led Kadima to a less convincing election victory on 28 March; and was confirmed as prime minister on 14 April, the day Sharon was declared "permanently incapacitated", having been in a coma for 100 days.

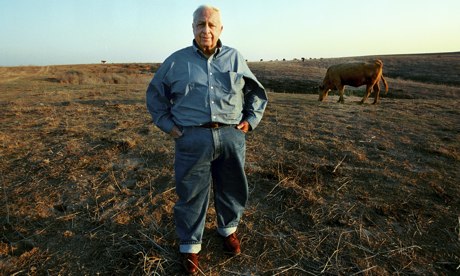

Most outsiders will remember Sharon as a military dynamo and hardline Zionist. Yet in private he was said to be a contemplative man, who only felt true peace on his 1,000-acre farm in the arid Negev, and hid a tragic private life. His beloved first wife, Margalit, died in a car crash in 1962; her sister, Lilly, his formidable second wife, succumbed to cancer in 1999; in 1968, his favourite son, Gur, was killed in a shooting accident. He is survived by his sons Gilad and Omri.

• Ariel Sharon, soldier and politician, born 26 February 1928; died 11 January 2014