When Esther Calhoun marches across the Edmund Pettus bridge this weekend, it will be for a right she says is more fundamental than the vote. “I want to breathe clean air,” she said.

Her home in Uniontown, 30 miles west of Selma, is described by environmentalists as one of the most polluted, exploited and contaminated towns in Alabama, a state with notoriously lax environmental standards.

Calhoun, a 52-year-old mother of two, depicts the struggle against the 4-million tonne coal ash dump that has sprouted on the edge of town, and the raw sewage seeping into local streams, as a modern-day civil rights campaign.

“People don’t listen to us because we have black voices,” said Calhoun, who was born on a Uniontown plantation three years before the famed march in Selma, and picked cotton growing up. “Everyone says, ‘now we’re free’, but I don’t think I’m going to be free until I’m dead.”

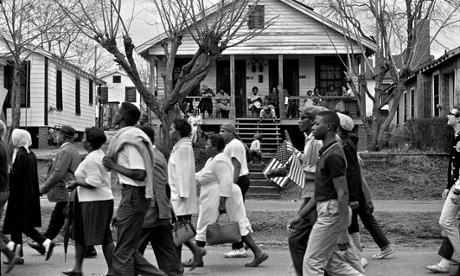

On Saturday, she will be among tens of thousands of campaigners descending on Selma for a weekend of events commemorating the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday - the day when 600 civil rights demonstrators calling for the right to vote were brutally beaten by state troopers preventing them from crossing the bridge en route to Montgomery.

Television images of the crackdown on peaceful marchers stunned America. It represented a watershed in civil rights history that paved the way, months later, for the Voting Rights Act.

Two years ago, a key provision in that legislation was struck down by the supreme court. Organisers of the commemoration, which will be attended by Barack Obama, his predecessor, George Bush, and more than 100 legislators from Washington, want to use the anniversary to call for a renewal of federal voting rights legislation.

Few if any this weekend will disagree with those aims. But 50 years on from Selma, activists heading to the small town are motivated by a more diverse set of causes, from the environmental protection through to gay and immigration rights.

Obama himself used an interview with SiriusXM show Urban View on the eve of his speech in Selma to call on younger generations to adopt a broader interpretation of civil rights, viewing immigration reform and same-sex marriage as part of the same struggle.

“When you think about the principle that was upheld that day, and in subsequent days, at the Edmund Pettus bridge, it was the promise of an inclusive America,” he said on Friday.

“One of the great reasons that we celebrate that heyday of the civil rights movement is that it didn’t just open up the doors for black folks,” Obama said. “It wasn’t just about black folks; it was about America, and who were are, and the legacy that then opened the doors for Americans with disabilities, and Latinos, and Asian Americans, and women.

“We have to understand what that spirit was about. It wasn’t just about one race, it was about who all of us are.”

Uniontown

Calhoun’s mobile home is right next to the train line that ferried the coal ash from a power plant spill 300 miles away in Harriman, Tennessee.

By 2011, when the last of the coal ash had been shifted from Harriman, a town which is 90% white, to a landfill on the outskirts of Uniontown, which is 90% black, it had formed the highest peak in Perry County.

When the coal ash first arrived, residents complained of upper respiratory infections, nosebleeds and nausea. Scientists said they found evidence of arsenic leaking into local streams and residents closest to the landfill said paint was stripping off their cars.

A civil rights complaint against state regulators, which granted the permit for the giant coal ash deposit, has been filed to the Environmental Protection Agency by residents, with the help of the non-profit group Earthjustice.

A decision by the EPA’s civil rights division is pending and, whatever happens, the coal ash mountain is not going away.

It is one of several environmental problems afflicting Uniontown. Adam Johnston, a coordinator for Alabama Rivers Alliance, said thousands of gallons of under-treated and sometimes raw sewage flows into local streams each week, because the residential water treatment plant is overburdened by a Catfish processing plant and a private prison.

A $4.8m subsidy from the federal government to upgrade the sewage system has been mismanaged, Johnston said. In an unrelated problem, locals also complain about the odor emitted by the cheese factory close to Calhoun’s home.

When Calhoun’s daughter visited in the summer she said she could not play outside “because of the flies, and because the air irritated her skin”.

Her neighbour, Ben Eaton, 55, a retired teacher, said he lost his sense of smell a few years ago, but still knows when there is a problem in the air. “I can feel it,” he said. “The air is dense and my eyes burn.” He also recalled the dust when the coal ash first arrived. “It was so thick it looked like grey snow on the trees.”

Calhoun and Eaton explain the town’s predicament in terms of race and poverty. They say it’s unthinkable that a rich, white town in Alabama would be treated in the same way.

Yet they blame local black officials for the pollution – and particularly the coal ash mountain, which poured money into depleted coffers of Perry County. “We’ve been let down by our black leaders who got power,” said Calhoun.

The local official most frequently blamed by locals is Albert Turner Jr, a county commissioner who is trying to find ways to bring more yet more coal ash to Uniontown. Turner is the son son of Albert Turner Sr, a civil rights hero who advised Martin Luther King and helped lead the Selma march.

Despite the civil complaint to the EPA, Turner Jr insisted the coal ash was safely deposited in the landfill and repeated his pledge to bring more coal ash to the town.

He was nonplussed at the notion that Uniontown residents would be joining the 50th anniversary of the Selma march to call for environmental civil rights.

“That may be the reason they are coming to Selma, but it won’t have any effect,” he said.

Montgomery

Of course, similar arguments 50 years ago did not dissuade Turner’s father from leading the march from Selma to Montgomery.

Despite the shocking crackdown, the marchers arrived at the steps of the state legislature in Montgomery two weeks after Bloody Sunday, defying Alabama’s segregationist governor, George Wallace.

Today, it it is another branch of Alabama’s state government that is responsible for what some argue is the state’s most egregious assault on civil rights – one that is unconnected to racial discrimination.

Alabama’s supreme court is taking a firm stand against gay marriage, barring local probate judges from issuing licenses to gay and lesbian couples. The tension between state and federal rulings has echoes of the civil rights era.

Just two days ago, the all-Republican court ruled 7-1 that Alabama’s 68 probate judges must stop issuing marriage licenses to gay and lesbian couples.

The figurehead for Alabama’s anti-gay movement is the court’s staunchly conservative chief justice, Roy Moore. He recused himself from the decision because he had already ordered probate judges to ignore an earlier judgment that ruled the ban on gay marriages in the state was constitutional.

“Judge Roy Moore, in the end, is on the wrong side of history, just like George Wallace when he stood in the schoolhouse door,” said 24-year-old Kindred Motes, one of the many LGBT people traveling to Selma this weekend.

The gay marriage issue is widely expected to be settled in June, when the US supreme court rules on a whether gay couples have a fundamental rights to marry, against the wishes of resistant states such as Alabama.

Immigrant rights

Alabama attorneys and court clerks – and even some judges – have been known to eat ribs at a Montgomery BBQ restaurant a short walk from the state’s neo-classical judicial building.

Few if any will know the name of their female waitress, Irma Alvarez, or her partner, Noe, the man who spends hours smoking the ribs in the kitchen. Irma and Noe, undocumented migrants from Mexico with a four-month old son, Amri, are denied many of the basic civil rights enjoyed by their patrons and live at risk of deportation.

Both could obtain a temporary reprieve under the Obama’s controversial executive order, which was intended to shield millions from deportation but was dealt a blow last month by a ruling from a federal judge in Texas.

Alabama rivals Arizona as one of the most inhospitable states for undocumented workers. Four years ago the state legislature passed HB56, at the time considered the most punitive anti-immigration law in the country, intended to “attack every aspect of an illegal alien’s life” and encourage the state’s migrants to leave.

It worked. “[After] the law was passed, people began leaving their jobs, packing their things, and then they left to other states,” said Ingrid Chapman, who runs the Alabama Coalition for Immigrant Justice. “In the first week alone, 2,500 Latino children left Alabama schools.”

HB56 has since been defeated in the courts, but its legacy lives on. Noe, 43, who was subject to a traffic stop by police when the law was still in effect, was temporarily jailed and now faces an immigration hearing that could result in his deportation.

Irma and Noe have been working double shifts in the restaurant so they can spend the next three days in Selma protesting.

“The world is changing, and Alabama needs to catch-up,” said Irma, who said she recently visited the Rosa Parks museum and saw parallels with the civil rights movement and the campaign for equal rights being waged by migrants today.

“We want to create a union with African Americans,” she said. “We want equality too. I say ‘we’ because we are part of this community now.”

Additional reporting: Verna Gates