Apple's chief executive, Tim Cook, may be top of the league of America's best-paid company bosses, newly showered with $378m (£240m) in cash and stock options, but his consumption has never been conspicuous. There are no superyachts, no garages full of luxury cars. Even after selling more than $100m in stock, Cook continued to rent a modest home. In 2010, with the multimillion-dollar Californian real estate market at his mercy, he eventually bought a four-bedroom, ungated property in Palo Alto for a grand total of $1.9m.

There may have been growing concerns about Apple's human rights record at the factories in China that manufacture some of its products; but there was little evidence in its recent record-breaking results of consumers voting with their wallets.

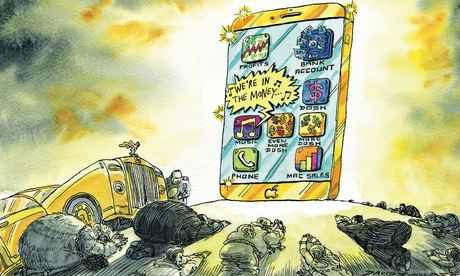

Apple has now amassed an extraordinary $98bn cash pile. For the frugal Cook, it is an almost embarrassingly large sum. The hoard could easily reach $150bn by the end of this year – more than the US government's operating cash balance.

Wall Street speculation about how Cook will choose to spend his reserves is now at fever pitch. Unconfirmed reports suggest the company is about to take one of the biggest gambles in its history: an internet-connected TV. If it works in the way the iPod and iPhone worked, the iTV will light a fire under Hollywood's mighty film and cable television conglomerates in the way its predecessors disrupted the giants of music and mobile telephony.

An exciting prospect, but a frightening one for investors, who would prefer Apple to share some of its profits before gambling them on new ventures. The company's late founder, Steve Jobs, was not a fan of dividends, and between 1995 and his death last year, Apple steadfastly refused to pay one.

Under Cook, the mood music has softened. "I would characterise our discussions today as active, about what makes the most sense to do with the cash balance," chief financial officer Peter Oppenheimer said during a conference call last week. "But we don't have anything to announce specifically today."

After such hints, analysts now expect a payout this year. They may have an ally in Disney chief executive Bob Iger, who took Jobs's seat on the Apple board. After successful collaborations on hit films Toy Story and Finding Nemo, Iger made Jobs his largest shareholder in 2006, when Disney paid $7.4bn in shares for Jobs's computer animation studio Pixar (bought for a mere $5m in 1986).

Disney is a fan of big dividends. After record sales and profits, it increased its own shareholder payouts in December by 50% to $0.60 a share. The irony was not lost on Apple investors, who watched Jobs's estate, the Steven P Jobs Trust, reap $82.8m from 138m Disney shares.

Around two-thirds of Apple's hoard is held overseas, which limits the amount of cash that can be shared with investors because the US government allows businesses to defer paying tax on money earned abroad until it is repatriated.

Apple and two other technology giants, Google and Cisco, are lobbying Congress for a tax holiday on more than $1 trillion in offshore profits, but even so, Tavis McCourt at broker Morgan Keegan reckons Apple could fund a dividend from its US-earned cashflow alone, without having to dip into the reserves. This would produce a payout of between $10 and $11 a share each year. Failing that, a share buyback would be welcome – or Apple could blow a few billion on a major acquisition.

"Investors get scared about large accumulations," warns McCourt. "The more cash stockpiles, the more fear builds they could make a big dumb acquisition."

There are precedents for this among technology companies, as fading giants turn to retail therapy in search of a pick-me-up. Last year, Microsoft paid $8.5bn for loss-making internet telephony group Skype, while Hewlett-Packard, the world's largest PC maker, parted with an extraordinary £7bn for the British search software group Autonomy after being faced with a decline in its core products, as tablets and smartphones gain popularity.

The often-cited possibility of Apple buying a mobile phone network would get a thumbs-down from Wall Street. Networks are expensive: America's smallest national operator, T-Mobile, would have cost AT&T $39bn had the takeover deal been approved. Apple's cash could buy it masts in its home market and two or three others – not enough to compete with a Vodafone or a Telefónica, but a surefire way of angering its best customers, the mobile firms.

There are two obvious big-ticket investments Apple might contemplate. The first would be to expand its army of 350 stores, particularly in the far east. As it branches out, Apple could accept lower retail margins in favour of better customer service.

Last year Chad Ramey, one of Apple's "geniuses", as it calls its technology helpdesk staff, quit its Arrowhead store in Glendale, Arizona after three years and published an open letter complaining of a drop in standards. The retail experience had gone from "something truly spectacular" to Walmart-style "big-box retail", he warned. Employees were "forced to worry more about pushing business leads and reaching numbers, rather than truly focus[ing] on the customer's problems," wrote Ramey. A few more staff in a few more Apple stores could help customers feel more supported as they wrestle with all the new technology in their homes. The shops could have an important role to play if Apple forges ahead with its rumoured foray into television.

The company's lips are sealed, but factory reports suggest a fully-fledged smart TV is planned for later this year. Unlike Apple's existing TV gadget, a small box that connects your existing set to the internet, the iTV will come with a screen as well as a brain – and a subscription to iTunes, according to professional Apple-watcher Carolina Milanesi at research firm Gartner.

In the same way that iPhone buyers cut the upfront cost of the handset by signing a two-year calls contract with a network, customers could spread the cost of a TV by taking a subscription to rent films and drama series from the iTunes store.

Milanesi is convinced that the new device "will definitely come with a service". "It will be what you have today on iTunes, with a subscription rather than just pay-per-view. What are they going to offer that Netflix doesn't? It comes down to content. It has to." To persuade customers to spend more, or even swap their Sky or Virgin premium channels in favour of an iTunes subscription, Apple will need an eye-catching array of content. But exclusive first-run pay-TV rights do not come cheaply.

Does Apple want to be a media company? Arguably, it already is. Gross revenues from iTunes, which totalled $5bn (£3.2bn) in 2011, are greater than ITV's £2bn turnover and on a par with the BBC's annual budget of £3.5bn. They are equivalent to a third of Amazon's $15bn takings in 2010 for global media sales.

Of course, Apple may prefer to let others do the work. Its spokespeople took the rare step of going on the record to deny a recent report that it was planning to bid against Sky for English Premier League football TV rights.

In any case, online TV and film rental services such as Netflix and LoveFilm have financial firepower and are already snapping up top-flight content. And, foreseeing the threat, incumbent pay-TV operators like America's cable companies or Sky in the UK will be manoeuvring to shore up their own position.

What video-on-demand companies need in order to achieve lift-off is the kind of user-friendly, elegant interface that Apple excels at creating. But whether or not Cook decides the future lies in selling pay TV, he will find it increasingly hard to resist sharing the spoils with Apple's shareholders.