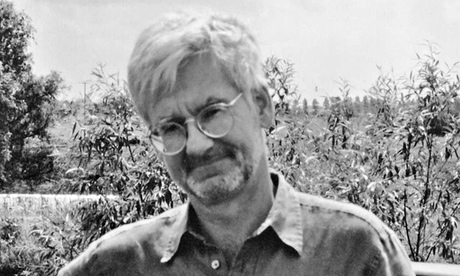

Sir Christopher Bayly, who has died suddenly aged 69, was the pre-eminent historian of India and the British empire and a pioneer of the field of global history. In 2007 he was the first scholar to be knighted “for services to history outside of Europe”. His adult life was anchored in Cambridge, where he was fellow of St Catharine’s College from 1970 and professor of imperial and naval history from 1992 to 2013. But his distinction was international: he held appointments and received honours in India, Europe, the US and Australia; and at his death he held concurrently professorships at Chicago, Copenhagen and Queen Mary University of London.

Bayly was a virtuoso historian, both prolific, writing a dozen influential books, and with an unequalled intellectual range. His work crossed economic, social, political, cultural and intellectual history, the histories of the visual arts and the natural sciences, of intelligence and war. It spanned the last three centuries, and from its focus of attention on Asia, intervened in the histories of Britain, Europe, the Americas and the Pacific.

He read everything and might be found in the break before lunch quietly browsing through a treatise on Japanese archaeology or Ethiopian land tenure practices, far from his field. He had an astonishing capacity to respond quickly to new perspectives and had the knack, in particular, of grafting historical ideas from one specialism to another, finding connections, for example, between 18th-century Mexico and India. He similarly read widely across the social sciences and had a magpie’s eye for something brilliant in another discipline. The award to him in 2005 of the Wolfson prize for history, not as is usual for a single work, but for his entire oeuvre, offers some index of how he was prized as a historical intellectual across the discipline.

Bayly was born in Tunbridge Wells, Kent. His curiosity about the wider world was spurred early on by the travels of his father, Roy, a master mariner and later geography teacher, and by the stories told by his working-class maternal grandfather, of serving as a private with Viscount Allenby in Palestine in 1917. He was close to his father, a disappointed Liberal council candidate, with whom he recalled having his first ever political argument, about Suez in 1956. But the more direct influence on his intellectual ambitions was his mother, Elfreda, with whom he maintained a close relationship until her death last year.

The history he was taught, at the Skinners’ school, Tunbridge Wells, and initially at Oxford, where he went to Balliol in 1963, was exclusively European. But a long vacation journey across land to India in 1965, passing through Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan, sparked his passion for Asia. Professor Jack Gallagher, then leading a revolution in British imperial history, took him in hand, and by 1966 Bayly began a thesis on Indian history.

He was lucky to live in a golden age of Oxford history. Christopher Hill, Richard Cobb and Gallagher, his Balliol tutors, had a lasting impact on his intellectual style and voice, as did those such as Keith Thomas around the journal Past & Present who were then showing how history might conduct a productive dialogue with anthropology and sociology.

Their mark can be seen in Bayly’s declaration in 1998 that while he was politically a liberal, “historical analysis in the Marxist tradition is the only social theory which displays a rigorous interest in explaining historical change”.

He was lucky too to come to his subject after the Hayter committee on Area Studies of 1961 had given India, Africa, the Middle East and Latin America their first precarious toeholds in British universities. St Antony’s, his graduate college, where Sarvepalli Gopal and Albert Hourani guided his reading in the histories of India and the Middle East, was the Oxford centre of this impetus.

Cambridge, however, where he arrived in 1970, on the invitation of Eric Stokes, his most important mentor, had the leading British research community in Indian history. While Bayly was never part of the Trinity-centred Cambridge school of Indian history, he derived stimulus from it, and his own initial arc of research into the social and economic history of India responded to its focus on the material basis of politics.

In his first body of work, in particular The Local Roots of Indian Politics (1975) and Rulers, Townsmen and Bazaars (1983), Bayly changed how we think about the local roots of the origins and end of British rule in India. The basis of this was his ingenious discovery of private archives in Allahabad and Benares, which no scholar had previously used and which illuminated the political and economic history of India from the inside in ways invisible from the India Office library in London.

Guided by this Asian-centred view of the making of the British empire, Bayly then developed in Imperial Meridian (1989) a new interpretation of the transition between the first and second British empires. Out of this, he became fascinated with how British imperial power in India brought the intellectual worlds of Britain and India together. A trilogy of key works – Empire and Information (1996), The Origins of Nationality in South Asia (1998) and Recovering Liberties (2011) – elucidated how Indians responded as active agents to western science, nationalism and liberal political and economic thought.

Bayly was also a brilliant global history comparativist who, in a series of connected monographs, in particular The Birth of the Modern World (2003), offered influential reinterpretations of the patterns of convergence in world history between 1750 and 1900. He died having completed a 20th-century sequel, and with plans for a new book of essays on world historians.

Bayly was a provocative undergraduate lecturer and mentor of dozens of doctoral and post-doctoral scholars. He mixed a rare capacity to understand what others were trying to do, sometimes before they did, with a respect for others which made him able to pay attention. He was a kind man, offering advice and practical help when it was needed. He strongly believed that historical research was a friendly conversation across generations, if at all possible over plentiful wine, and he treated his younger colleagues and students as equals.

This made possible his extraordinary gift for intellectual collaborations. The most enduring of these was with Susan, the Cambridge historian and anthropologist whom he married in 1981, and with whom, he joked, he ran a permanent seminar over the dinner table. As striking was his ability to share work with the next generation. He wrote two books on wars in Asia with his former student Tim Harper, while editing books with Peter Bang in Copenhagen on comparative imperial history and with Jens Hanssen in Toronto on Hourani. He spent his last decade in a conversation with Shruti Kapila in Cambridge, and later Faisal Devji in Oxford, towards a new Indian history of political thought.

Though his work ethic was stakhanovite, his instincts were epicurean and romantic. Bayly was fond of good food and drink, particular mixed with animated conversation. He collected paintings and sculpture, and loved Italian opera, in particular Verdi. He and Susan spent two weeks each summer in Venice. He had a lifelong love of animals, which extended to his being sighted in Cambridge, more than once, in the early morning, shepherding duck and ducklings who had strayed into the city back towards the river Cam.

He was animated by a moral, even utopian, purpose. If one might find a hidden emotional spine to all his historical work, it would be a hope for a cosmopolitan liberal future, in which human beings, beyond race and nation, would live compassionately in a family of democracies. He wanted a 21st-century global future for his kind of liberalism, to which his illumination of Indian traditions was quietly intended to be a contribution.

Bayly was a fellow of the British Academy, the Royal Historical Society and the Royal Society of Literature, and also a member of Academia Europaea. He became a trustee of the British Museum in 2008 and was awarded the medal of the Royal Asiatic Society in 2009. He was made Doctor of Letters honoris causa of King’s College London in November last year.

Susan survives him, along with his younger brother, Jonathan, and his nephews and nieces, Martin, Christopher, Rosemary and Kathryn.

• Christopher Alan Bayly, historian, born 18 May 1945; died 18 April 2015

• This article was amended on 24 April. The list of Christopher Bayly’s immediate surviving family members was completed.