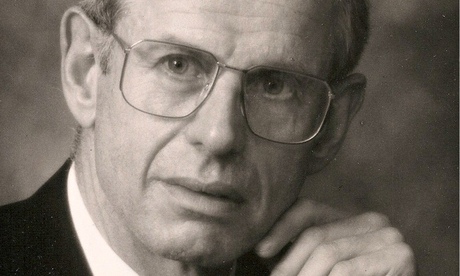

My colleague and friend Howard Nicholson, who has died aged 102, was a chest physician, an inspirational diagnostician and a teacher.

After the second world war, as a consultant at two London hospitals – University College (UCH) and the Brompton – Howard began to run patient treatment meetings on what we would now call multidisciplinary lines. Treatment decisions were made jointly by physicians, surgeons and radiologists, with physiotherapists and social workers also contributing. Joint care planning is now taken for granted, but it was pioneering at the time and Howard was instrumental in getting it off the ground.

Despite being a chest specialist he had also studied radiology, which gave him a wider perspective than some of his peers. This allowed him to see the value of bringing in opinions from as many disciplines as possible.

Born in Houghton-le-Spring, Sunderland, Howard was brought up by his mother, Sarah Harrison, a teacher, and his grandmother after his father, Frederick Nicholson, a mining engineer, was killed in the first world war. Howard came to London to study medicine at UCH in the early 1930s, qualifying in 1935, and, while working at King Edward VII Sanatorium in Midhurst, West Sussex, he met Winsome Piercy. They married in 1941, shortly before he was sent to the Middle East with the Royal Army Medical Corps thoracic surgical unit, where he worked with the Scottish cardiothoracic surgeon Andrew Logan.

Howard often spoke of his time in Egypt with Logan, which widened his horizons and knowledge considerably, and some of their experiences were recorded in two fascinating papers that the pair published in the Thorax journal (1948-49). Howard subsequently co-authored two of the first papers evaluating antibiotic treatment for tuberculosis in the Lancet (1955-1960).

His skills and insights were appreciated by many, not least Margaret Turner-Warwick, who trained under him at UCH and who was later the first woman to become president of the Royal College of Physicians. In her book Living Medicine she wrote of his "logical and analytical approach" but also of his kindness and his skill at dealing with "difficult colleagues, troubled patients and truculent students". In the early 1970s I was one of those lucky enough to study with him.

Howard's great-grandfather was Joseph Skipsey, "the Pitman Poet", and Howard too was a man of culture. He had a great love and knowledge of English literature and of opera, settling on retirement with Winsome near Glyndebourne. During his last years, when he was more confined to his cottage in Sussex, his Christmas treat was to re-read the Jane Austen canon, starting on Boxing Day.

Winsome predeceased him.