‘Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a hard battle.” Over the past few weeks, I have become freshly aware of the wisdom of this saying, aware both of this great battle we fight and of the kindness of people that runs like an underground river beneath the noise and hurtle of public events.

Two months ago, I wrote a piece in the Observer about the death of my father, who had had dementia for many years, but had been leading a contented life at home until he went into hospital with leg ulcers. I described how he entered able to walk, talk, wash himself, feed himself, work in his beloved garden, listen to poetry, be happy – and how, five weeks later, he came out a skeleton, incontinent, immobile, inarticulate, bed-bound. He lived like a ghost in his own life for eight more months; his dying was both a great sorrow but also his release.

I wrote the piece because I believed that what happened to my father happens to many others and however wonderful the nurses and doctors are (and they are!), hospitals cannot cope with the number of demented people who occupy the beds, fill up A&E, need feeding, hydrating, but also constant, reassuring attention. The hospital experience can be bewildering, terrifying, catastrophic for them.

At the end of my article (trying to rescue my father who is now beyond rescue), I announced John’s Campaign, the brainchild of my co-campaigner, Julia Jones, whose 90-year-old mother has Alzheimer’s, which has a simple, achievable aim: to allow carers of demented people the right to accompany them in hospital, just as the parents of sick children do. These carers could feed them, keep them mobile, be their voice and memory bank, anchor them to the world.

The response to that piece and pledge, by Facebook and Twitter and email and in person, has been inspiring and heartbreaking in equal measure. First of all, there are the hundreds of stories that people have shared and the community of suffering and of goodness these stories reveal. These accounts ring multiple variations on the same theme: their spouses, their parents, were broken, often beyond repair, by their stay in hospital.

The 84-year-old wife who had to travel by taxi to visit her husband for the two-hour slot and who wasn’t allowed to stay for Christmas dinner; the son battling to keep his frail mother out of hospital after his demented father died there; the patient who lost 66lbs in six weeks; the daughter whose father was in hospital for 14 weeks (“four bare walls and a sink”), where “the plug was pulled” on his life. Stories poured in, full of anger, guilt, powerlessness and loss, ones of encouragement, optimism and advice, and they are still coming. It seems that everyone we meet has a tale to tell and that we have reached a point in our aging society where no one is untouched by the blight of dementia.

Few who have contacted us blame individuals or even hospitals; they recognise that good nurses are coping as best as they possibly can in an unsustainable situation. There are 800,000 people with dementia in the UK; there will be 1 million by 2020, more than 2 million by 2051. There are more than 500,000 carers – worn-out, unsung heroes. One in three people will care for someone with dementia at some point in their life. More than a quarter of hospital beds are occupied by people with dementia (no surprise to anyone who has been in hospital recently, where wards are full of men and women in great anxiety and torment) and they tend to stay for longer-than-average periods of time.

Hospital is an extremely hazardous place for patients with dementia. Of the people who are admitted from their own home, one third never return there. One third. Think of what that means; think of the cost to the public purse, to the carer whose care has been interrupted and undone, to the life of the person who is ending their days in distress and pain – and who could be our loved-one soon enough, ourselves. Old age can be scary, but the time for denial is over.

We expected resistance from hospitals and experts and were ready to counter them. Costs: there aren’t any, unless hospitals choose to put a reclining chair by the bed, while the benefits are vast. Health and safety: they do it in children’s wards and in other countries. The carers’ need for respite: this is a right, not duty. The plight of patients without carers: the nurses will be able to give them more time… But in fact, we have met only help and encouragement. We have found there are many tireless groups and individuals who have similar aims to us.

The Alzheimer’s Society has been generous in its support (and in getting us into meetings). Indomitable, humane senior nurses have backed us and shown us examples of enlightened practice, where old, frightened people are treated with respect and humanity. Some hospitals have pledged to roll out our campaign. Indeed, there are several where there is already open access for carers – but often this is theory. Hospitals are “dementia friendly” – in theory. They can point to their policies and explain their rules and tick their boxes, as if that were enough. Meeting ineffectual agreement can be more frustrating than outright opposition, like punching a paper bag or pushing bureaucratic sludge. People are kind; fragmented systems can grind you down.

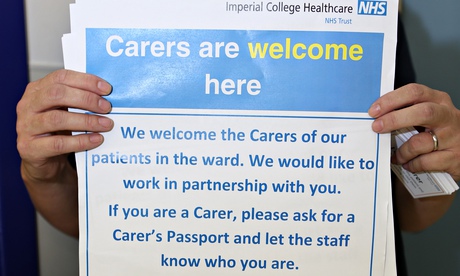

Mind the gap. Theory is not practice. Carers should not have to research hospital policy or fight their way on to wards; the right to access should not depend on individual staff or hospitals, but be an inalienable right. It should not be granted, but actively and wholeheartedly encouraged, because it is in everyone’s interests. We want a poster (a large poster) on every entrance of every ward in every hospital, up and down the country: “CARERS WELCOME”. There’s a door that has to be opened: it has to be pulled by the hospital staff, pushed by the public. And it needs to be taken off its hinges by politicians.

And where are the politicians in all of this? On The Andrew Marr Show, following my interview, David Cameron, who has made dementia a national priority, said there was “a lot of merit” in the idea. Good: so what will he do next? MP Valerie Vaz tabled an early day motion in support of the campaign: of the 52 signatories, only four are Conservative. Norman Lamb, minister for care and support, has agreed to meet us next month but in a letter responding to an MP’s query said that it is up to individual hospitals. He wouldn’t say this about disability access: it should not be voluntary to follow good practice.

There used to be a kind of shame around dementia (they “died after a long illness”). Now the shame is how we treat people with dementia. Our campaign only deals with one small part of that treatment, but it’s simple, cost-free, of benefit to everyone, a matter of commonsense and common kindness. It’s optimistic and achievable. It will happen eventually but should happen soon; now. Take those doors off their hinges. Let us in.