In 1964, Bob Dylan wrote many of the songs on Bringing It All Back Home in a spartan “white room” he’d been loaned above the Café Espresso in Woodstock. About 100 miles north of New York, the small country town is lodged at the foot of wooded hills, between the Catskill mountains and the Hudson river. When Dylan was writing in residence, Woodstock had long been a magnet for artists. In the early 20th century, painters came to capture its natural charms and a rural arts colony flourished, but by the time Dylan arrived the town’s woods, creeks, and shaggy skyline were less of a draw. In the early 1960s, Woodstock was simply not New York.

It was a bolthole not a beauty spot, some green calm after Manhattan. But previously the place had got under the skin of those who lingered, and the town’s mood reflected more than the sum of its arts. Mightn’t then the modern creatives come to sing of it as well? Can we hear Woodstock when we listen to Dylan?

Barney Hoskyns is not sure. He writes early on in Small Town Talk that he believes in “a psychogeography that may be little more than romanticism but that enshrines something good about the people who have lived here”. Having said that, he cannot muster much evidence of good people. And although he knows of an astonishing number of musicians, hundreds and more, who passed through Woodstock (and in some cases settled), and has put them all in a book written around the place (a town that he’s lived in himself), it remains uncertain in what way and to what degree the place has operated on its people. Mostly people operate on people in Hoskyns’s tale. And, mostly, without anaesthetics.

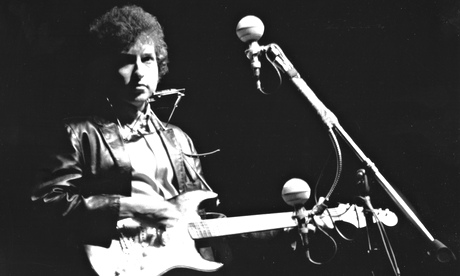

The exceptions (temporary, but making up the best part of Hoskyns’s book) are Dylan and the Band. Dylan had already been tangled up in Woodstock for several years, but rock lore has it that the spirit of the place touched him most emphatically as a result of his motorbike accident there in July 1966 (Hoskyns includes a good map with all the salients clearly marked). This slowed him down creatively as well as mechanically.

But, only weeks after he’d gone electric on stage, Dylan gave up on machine noise and turned (emotionally) towards his new young family and (musically) towards the woods around his bosky house; towards the back country, or (depending on which musical dowser you follow) towards Americana, or alt-country, or “palavers with a community of ghosts” (Greil Marcus). He didn’t sing in front of a live audience for ages and his next two albums were John Wesley Harding (1967) and Nashville Skyline (1969): both unacknowledged Woodstock albums. Between these came The Basement Tapes, the magical recordings Dylan made with the Band, mostly at Big Pink, a house (apparently rather small) on the edge of town. And it’s the Band who, more than any other artist or ensemble in Hoskyns’s book, come to epitomise the mood music of Woodstock – whose songs, Hoskyns says, were “made organically by men who’d pulled back from the insanity of fame”.

Woodstock was the place, Dylan said, where “we stop the clouds, turn time back and inside out”. But despite his happy shouting from the basement, those organ swirls and gospel hollers, this is mostly a sad book. A sad book about a place that people gravitated towards thinking that it would chase all sorts of blues away. It is sad, in part, because it is a book about (often great) music and, although it comes alive when it talks about the sound of that music (Hoskyns is harsh on Dylan, but brilliant at two-word summations of the gist of a song), mostly what sustains it is people talking about what they or others did around the music – and that is too often dreary. It is also sad because it tells things chronologically, with the second law of thermodynamics swung like a wrecking ball through the musicians of the time. By staying until the bitter end, with the lights fully up and hiding nothing, there are many bitter ends for Hoskyns to annotate. None worse than the grim story of the dissolution of the main act, the house band, who once did the best small-town talk around.

A lot of this is not Hoskyns’s fault – if you linger long enough most things die, and it is in the nature of communes and collectives and rock groups that they breed division and hate. And the truth is that Woodstock is home ground – a place that you might bring it all back home to – for hardly anyone. Dylan’s children are among the very few.

Much of value survives in Hoskyns’s account, however. Incidental stories are legion. The roster of sometime Woodstockers is extraordinary – Hendrix, Van Morrison (terrified of meeting Dylan, but desperate to do so), Todd Rundgren, Paul Butterfield, the great English jazz bassist Dave Holland, another Englishman, Graham Parker – all have numbers in the Woodstock musical. The testimonies of the singer Maria Muldaur and the poet and former Fug, Ed Sanders, are especially good and have a truthful tang. There are also the mandatory rock niceties of catastrophic drug binges and naked girls offering blowjobs to (and under) the stars. And there’s the comedy of the Woodstock festival that, like a fata morgana, still lures the unwary into town, while the thing itself happened over the hills and 60 miles away, and simply pinched the town’s name to steal some of its draw.

But still one character poisons the well that the whole town has had some time to drink from. Hoskyns’s determination to put Albert Grossman at the centre of his story is risky. Grossman was the manager of Dylan, the Band, Janis Joplin, and many others. He also bought up swaths of the town and opened restaurants and built the Bearsville studios in Woodstock (anyone out there still listening to Foghat?). He’s worth seeing in plain, clear light, but the sight is awful. He seems to have been vile. “Saturnine,” Hoskyns says. “You could smell him coming,” said Dylan, who split from him at great expense. The cumulonimbus they called Grossman. That is all you need to know. Unstoppable cloud. Bad weather. And you feel it more, out there, in the woods and the hills.

Tim Dee is a writer and radio producer. His programme about Woodstock, Hippy Internet: The Whole Earth Catalog, was broadcast last December on Radio 4. Small Town Talk is published by Faber (£20). Click here to order a copy for £16