Historians love to identify a particular year as world-shaking or otherwise important, and write a book about it. Recently, popular histories have appeared of 1913 (the “year before the storm”), 1968 (“the year of revolt”), and 1980 (the “year of free markets”). By comparison, the 1950s remain oddly neglected. Perhaps the decade is seen as too dreary or drab to have diverted the course of history decisively. Certainly 1950s Britain was a derelict, half-ruined place, where railway carriages were black with grime and bomb damage showed in the big cities. It was the world of the screenwriter Dennis Potter’s “great greyness” – the “feeling of the flatness and bleakness of everyday England”.

In fact, Britain was on the cusp of tumultuous change in the 1950s. It was then that the sound barrier was finally broken and an “Elizabethan” age of aeronautical pre-eminence beckoned. Hair-raising cockpit dramas occurred as aviators were killed in engine flame-outs or were vaporised on impact with the countryside. Nevertheless, from these 1950s jet age catastrophes designers and engineers learned how to make commercial flight safe for us today. The science and aesthetics of faster-than-sound flight is a story that deserves to be told.

In the Soviet Union, similarly, the scientific astonishment and discovery of the mid-1950s was made real when the first Sputnik was lobbed into space and an era dawned of sleek ZiL cars, domestic gadgets and other “gracious” living. Apparatchiks at the vanguard of this scientific progress wore the latest in static-generating viscose suits, and subscribed to smart American computer journals. “The dreams mankind cherished for years are being turned into reality!” the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev enthused.

Khrushchev’s dramatic unmasking of Stalin in 1956 is central to Simon Hall’s marvellous social history of that year, The World in Revolt. Three years after the Soviet dictator’s death in 1953, Khrushchev gave what Hall calls his “secret speech” (though its contents were known across Russia and beyond in weeks); in it, Khrushchev denounced Stalin, along with the Soviet communist party’s “cult of personality” and the murderous state purges of 1937 and 1938. Khrushchev did not in fact admit to all the regime’s crimes – he was implicated in most of them – but his speech was a turning point for the 20th century. With it, the die was cast for Gorbachev’s glasnost 30 years later and the free-market crusades led in the west by Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. In that sense at least, 1956 was a world-shaking year.

During the uneasy thaw that followed Khrushchev’s 1956 denunciation and what became known as the “era of liberalisation”, the prospect of space exploration generated huge excitement in the USSR. Moscow became locked with Washington in an ideologically motivated battle to break through the bonds of the Earth’s gravity. Cosmonauts were not infrequently burned alive as they fireballed through re-entry, while a saltwater grave awaited astronauts on splashdown in the Atlantic. Such was the cost of progress in the 1950s.

Dangerously for Khrushchev, the spirit of de-Stalinisation unleashed by him led Hungary and other eastern bloc satellite states to agitate for independence. With “crude military force”, Hall relates, Khrushchev ordered Soviet tanks to crush the Budapest uprising of 1956; if it was not subdued, Khrushchev reasoned, the entire Soviet bloc threatened to crumble. Budapest was the Soviet president’s hardest, and ultimately most shaming, hour. His bitter, anti-intellectual envy afterwards combined with a growing paranoia and obsession with his own place in history.

By the late 1950s, it seemed that half the world was viewed in east-west, cold war prescriptions. In well-written pages, Hall chronicles Fidel Castro’s ill-fated attempt in 1956 to stage a nationalist revolt in Cuba. Che Guevara was the only non-Cuban aboard the cabin cruiser that ferried Fidel and 82 revolutionary patriots from Mexico to Cuba that year. After President Batista’s thuggish regime was finally overthrown by Fidel and Che three years later, in 1959, the idea of revolución “reverberated” divisively throughout the Caribbean and on into Africa. Fidel was a bogeyman bent on leading millions into the red bloc; JF Kennedy was a playboy capitalist and corrupt. Mercifully, such “us and them” foolishness is over today.

In their book on 1956, The Year That Changed Britain, Francis Beckett and Tony Russell consider (among other things) African-Caribbean migration from Jamaica and elsewhere in the Commonwealth. Unfortunately postwar Britain was not only unmindful of the Commonwealth but also disinclined, on racial grounds, to help West Indians. Italians selling ice cream were made more welcome, despite having fought on Hitler’s side in the conflict and experienced a good deal of hostility previously in Britain. Importantly, they were white, not black. Nevertheless, postwar Britain grew strong and rich by being open to the world. (Enoch Powell, the Tory health minister between 1960 and 1963, would invite West Indians and other Commonwealth citizens to come and work in the NHS, and thousands responded.) In London’s black quarter – its boundaries enclosing the Arch (Marble Arch), the Water (Bayswater), the Gate (Notting Hill) and the Grove (Ladbroke) – jazz-inflected calypso riffs could be heard alongside the Jamaican shuffle beat that became known as ska.

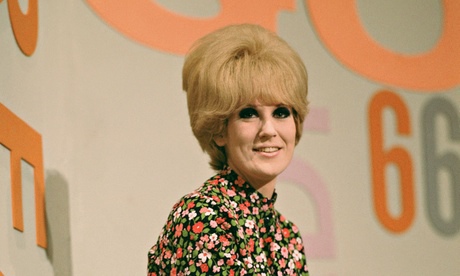

Jon Savage, a seasoned pop commentator, was barely a teenager in 1966 when British youth was galvanised by Motown. Reach Out I’ll Be There, by the Four Tops, became an anthem for scooter-riding mods and boomed out joyously from the Flamingo and other London music clubs. Savage’s absorbing musical-cultural history of 1966, The Year the Decade Exploded, is divided into 12 chapters – one per month – and captures the excitement of the times through its pop. Bob Dylan, the Beach Boys, the Beatles, the Byrds, Syd Barrett and the early Pink Floyd are all here, along with more off-piste acts such as the Birmingham-based the Ugly’s and the scarily tonsured proto-punk outfit the Monks. One way or another, says Savage, their music reflected the times.

So, too, did Sergeant Barry Sadler’s pro-Vietnam single The Ballad of the Green Berets, which reached No 1 in the US charts ahead of the Rolling Stones. Nothing could have been further removed from the swinging 60s’ anti-war movement; but, as Savage points out, 1966 was not all free jazz and free love. The north London band the Kinks were in some ways exemplars of working-class Toryism, who sought to preserve England’s “old ways” against the onslaught of Carnaby Street frivolity and dandyism. Though Savage’s book is littered with banalities (“Youth had a significant impact on western society”), it remains a marvel of historical reconstruction and pop insight.

1956: The World in Revolt is published by Faber (£20). Click here to buy it for £16. 1956: The Year That Changed Britain is published by Biteback Press (£20). Click here to buy it for £16. 1966: The Year the Decade Exploded is published by Faber (£20). Click here to buy it for £16