When William Faulkner was asked by the Paris Review to share his thoughts on the art of fiction in 1956, he offered several useful pieces of advice to the aspiring author. "A writer needs three things, experience, observation, and imagination – any two of which, at times any one of which – can supply the lack of the others," he declared. A writer must learn the tools of his trade; Faulkner's were "paper, tobacco, food, and a little whiskey". "Bourbon, you mean?" asked the interviewer. "No, I ain't that particular," Faulkner said. "Between Scotch and nothing, I'll take Scotch." And what would he say to people who complained that they couldn't understand his writing, even after they had read it two or three times? "Read it four times," he suggested.

Perhaps Faulkner was thinking of his 1929 novel The Sound and the Fury when he said this, as it is a book that takes the reader through the same story four times, from the perspective of four different characters – at which point readers just might, with luck and perseverance, have managed to piece together the narrative. When he finished the novel, Faulkner took it to his friend and acting agent, Ben Wasson, and said to him: "Read this, Bud. It's a real son-of-a-bitch … This one's the greatest I'll ever write." It took a while to catch on, but for the last half-century readers have agreed with Faulkner: for many, The Sound and the Fury is his greatest novel, and for almost everyone, it's a real son-of-a-bitch.

Notoriously, intransigently difficult, the novel takes its title from Macbeth's reflection that life is "a tale / Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, / Signifying nothing". It opens inside the mind of the "idiot", Benjy, a 33-year-old man who has the mind of a small child. (Benjy used to be described as "severely retarded"; he is now sometimes called "autistic", but as he is a fictional character in an era when such diagnoses were unavailable, it makes no sense to argue over what is "really" wrong with Benjy.) Faulkner uses stream-of-consciousness narration to suggest the way that Benjy's mind flows through time: memory, reality and emotion meet, shift, and kaleidoscopically recombine.

Benjy doesn't understand what is happening around him, and so cannot narrate the events he sees; Faulkner forces the reader to work out what is happening (and when) from the clues he drops. It is a kind of detective fiction, the kind that drives some readers crazy: but it also is a reductio ad absurdum of the act of reading itself. All reading requires the reader to infer meaning: the first chapter of The Sound and the Fury turns inference into an extreme sport. It moves through as many as 14 different moments across a 30-year period in Benjy's memory, often without any overt signal to the reader that a shift in time has just occurred.

At various points in Benjy's narration, Faulkner decided to use italics "to establish for the reader Benjy's confusion; that unbroken-surfaced confusion of an idiot which is outwardly a dynamic and logical coherence," he explained in a letter, adding: "I wish publishing was advanced enough to use coloured ink for such, as I argued with you and Hal in the speak-easy that day … I'll just have to save the idea until publishing grows up to it."

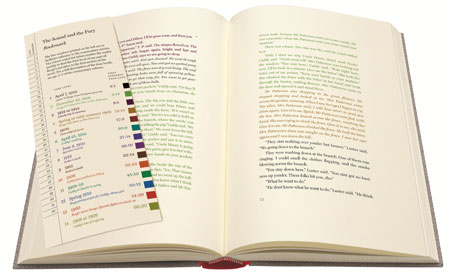

It seems that time has now come: Stephen M Ross and Noel Polk, two distinguished Faulkner scholars, have created a colour-coded version of The Sound and the Fury that the Folio Society is printing in a limited edition of 1,480 copies, each numbered by hand, on Abbey Wove paper with a gilded top edge, and quarter-bound in vermilion Nigerian goatskin leather blocked in gold; accompanying Faulkner's novel is a matching "line-by-line commentary and glossary" written by Ross and Polk. The sumptuous two-volume set will set readers back £225.

If some might balk at the conspicuousness of such consumption, others will appreciate the continuing effort to reinvent bound books as objets d'arts in an age of electronic publishing. The edition is unquestionably beautiful, a bibliophilic fantasy: the less aesthetic question is whether colour-coding helps or hinders us in interpreting Benjy's section.

It is not a question that Ross and Polk presume to answer easily; indeed, they acknowledge, it raises new questions: "in being so precise, they [the colour-codings] impose on the text a 'reading,' a third dimension, that the black-and-white text does not and so deny the reader the free play at work in the two-dimensional black-and-white, roman-and-italic text that is at once so daunting and exhilarating." The editors understand the risks, but they think it worth the experiment: "each reader will need to decide for him- or herself", they conclude.

Reading the colour-coded version kept reminding me of a line from Iris Murdoch's The Bell: "The conversation was not so much difficult as mad." Attempting a simple plot summary of The Sound and the Fury can bring on a migraine, and is an exercise in futility; trying to annotate it line by line, while painting each of Benjy's thoughts in a colour that has been matched to a particular point in time, feels like the project of a deranged scholar locked in some lunatic literary experiment devised by Jorge Luis Borges. And yet, as Borges also shows, such madness is the madness of art, like the brilliant, bonkers endeavour of Alfred Appel to annotate all of Nabokov's Lolita. It is fascinating, disruptive, distracting, maddening and enlightening, making a rainbow of Faulkner's stream of time.

The Sound and the Fury remained Faulkner's favourite; it was his fourth novel, and the second that he placed in fictional Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi ("my apocryphal county," he called it). The Sound and the Fury constituted an artistic breakthrough into the "sheer technical outrageousness" that would characterise such celebrated later works as A Light in August, As I Lay Dying, Go Down, Moses and the book that I, for one, would crown as Faulkner's masterpiece, the dazzling Absalom, Absalom!

He didn't stop there: eight more novels and at least half a dozen short stories were set in Yoknapatawpha, which Faulkner eventually mapped; he drew up genealogies and wrote afterwords and explanations, detailing the fates of the three families at the centre of his mythical world: the aristocratic Compsons and Sartorises, and the parvenu Snopes. Together they tell the story of the decay of the American South.

William Faulkner was born William Cuthbert Falkner on 25 September 1897, in New Albany, Mississippi; soon his family had relocated to Oxford, the town where he would live the rest of his life, and reinvent as the fictional Jefferson. When the young Falkner tried to join the air force in 1918, he was rejected for being too short. Deciding to pass himself off as an Englishman and enlist in the Canadian RAF, he changed the spelling of his name to Faulkner and invented a mythical British family for himself, using a forged letter of reference from one Reverend Edward Twimberly-Thorndyke. For whatever reasons, he never changed the spelling back when he went on to invent the equally mythical clans of Yoknapatawpha.

Faulkner never saw active service; in 1925 he published his first novel, Soldier's Pay, followed rapidly by Mosquitoes. He was convinced that his next novel, Flags in the Dust, the first Yoknapatawpha story, was his best yet, but to his shock his publishers turned it down; heavily edited, it was eventually published as Sartoris in 1928. The experience, said Faulkner, led to the breakthrough of The Sound and the Fury, as he gave up on publishers and set out to write the book he wanted to write.

"Now I can make myself a vase like that which the old Roman kept at his bedside and wore the rim slowly away with kissing it," he claimed to have told himself. "So I, who had never had a sister and was fated to lose my daughter in infancy, set out to make myself a beautiful and tragic little girl." There is more than a little mythmaking in such an account: but then mythmaking was already Faulkner's stock in trade.

Although his books were admired by other writers, Faulkner lived and wrote in relative obscurity for the first decade or so, until he wrote a bestseller called Sanctuary in 1931; it owed its success to its scandalously violent sexual content, including a scene in which a young woman is raped with a corncob and is turned by this experience into a prostitute for no apparent reason other than Victorian morality. Chronically hard-up, Faulkner found his way to Hollywood, where he collaborated on several now-legendary screenplays, including Mildred Pierce, To Have and Have Not and The Big Sleep. In 1949, he was awarded the Nobel prize for literature, and two of his subsequent novels, A Fable and The Reivers, which was published posthumously in 1962, both won the Pulitzer.

The Sound and the Fury is the story of the Compson family's decline and fall; when Faulkner was asked by a student why the Compsons are such a disaster, he answered: "They live in the 1860s." The novel ranges from 1900 to 1928, but the Compsons remain trapped in the obsolete attitudes and ideas of the South in the years of the civil war, destroyed by their futile attempts to live by dying prerogatives of class, race and sex.

The book resembles a Greek tragedy, telling the story of Caddy, the "lost woman", from the point of view of her three brothers – each of whom is also, in an important way, lost – and then finally from the perspective of the Compsons' black servant, Dilsey. Caddy is the novel's absent centre, the focus of all the characters but unreachable and unknowable – like the truth itself, some would say, as Faulkner offers only competing, subjective accounts. But the novel is also layered with what Faulkner called "counterpoint" – careful patterns of words and images to create an artistic unity that transcends the fragmented perspectives on display.

He claimed this "tragedy of two lost women: Caddy and her daughter" came to him first as an image of a little girl with symbolically muddy drawers; he loved it most, he said, because it "caused me the most grief and anguish, as the mother loves the child who became the thief or murderer more than the one who became the priest". The Sound and the Fury was always the book that Faulkner felt "tenderest toward," he said, "the most gallant, the most magnificent failure" of all his novels. "I couldn't leave it alone, and I could never tell it right, though I tried hard and would like to try again, though I'd probably fail again."

In 1998, the Modern Library ranked it the sixth greatest English-language novel of the 20th century, but Faulkner might have claimed to be unimpressed: "I don't care about John Doe's opinion on my or anyone else's work," he told the Paris Review. "Mine is the standard which has to be met, which is when the work makes me feel the way I do when I read La Tentation de Saint Antoine, or the Old Testament." Ultimately, he insisted, "the writer's only responsibility is to his art." If it made a writer ruthless, that was a price William Faulkner thought the world should be prepared to pay: "If a writer has to rob his mother, he will not hesitate; the 'Ode on a Grecian Urn' is worth any number of old ladies."

The Sound and the Fury limited edition is available from the Folio Society (£225). foliosociety.com/SAF