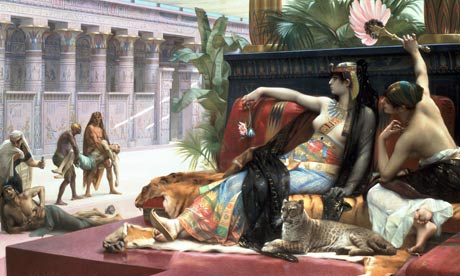

How, wondered Pascal, could he best sum up the causes and effects – the bliss and then, the bondage – of love? He found the answer in a single word – a woman's name: Cleopatra.

It's 20 years since a fine book by Lucy Hughes-Hallett undertook to disentangle the last and most resourceful of the Ptolemys from those myths which have masked her as an eastern whore (Boccaccio); a lustful sinner (Dante); an avaricious nymphomaniac (Cassius Dio); and – even further from the mark – a "silly little girl" (Shaw). Hughes-Hallett's work has now spawned a worthy successor. Ideally, as Stacy Schiff observes in her magnificent re-creation of both an extraordinary woman, and her times, our sense of Cleopatra would be heightened by her dramatic appearance as the doomed heroine of a sumptuous opera (Puccini, preferably).

That Schiff's book is the basis of a new Paul Greengrass film, due for 2013, seems like a good omen. It brings hope that Angelina Jolie may finally override the image of poor Elizabeth Taylor struggling to look imperial in inch-thick slap and a Folies Bergère head-dress. No previous image, visual or verbal, matches up to the inspiring, frightening, ruthless woman conjured by Schiff from an inspired combination of carefully parsed texts, new research, and pulse-quickening descriptive writing. (Not always, mind; '"Descent from Hercules is good enough for me," huffed Antony', is the kind of trashy writing that does a fine book no credit.)

Schiff uses a method that borrows much from the cinema. Zooming in on a dramatic event, she then pulls back to reveal the larger picture; the back story; the setting. Thus, she opens in 48BC with the banished Cleopatra, aged 21, camped out on the far side of the Nile delta, near Port Said, as she prepares for her long journey huddled within a soldier's shoulder-sack (she must have been both light and tiny, Schiff sensibly concludes) into Caesar's presence in her own Alexandrian palace. Cutting away, just short of the grand scene – Confident Invader disarmed by Audacious Intruder – Schiff turns the clock back. We all know what was about to happen: Schiff's artful shifts of time and location hold familiarity effectively at bay.

Comparisons between Rome (the city into which Cleopatra rode as Caesar's consort, while her rebel sister travelled, in golden shackles, among the throng of common prisoners), and Alexandria (to which Cleopatra prudently withdrew, following Caesar's assassination in 44BC) offer a surprise to anyone unacquainted with that remote era.

Non-scholars of the period tend to imagine ancient Rome looking as it does in many a sword-and-sandal epic: a fascist's paradise, all bronzed gladiators and sun-bleached marble. The Rome to which Cleopatra came was nothing of the kind. (An irony well noted by Schiff is that Rome's most glorious buildings were paid for, following the death of the 39-year-old queen of the Nile, with the vast treasure wrested from Egypt.)

Cleopatra's Alexandria, in contrast, was a city of dazzling luxury, beauty and culture; of broad, well-shaded avenues, ravishing mosaics, scholarly colleges, an unparalleled library, bookstores (Rome had none), and a social structure that – unlike Rome – allowed women formal education, divorce rights, property ownership and, most unusual of all, the chance to exploit their business skills.

As with the great city, so with the country; over a third of Ptolemaic Egypt, in Cleopatra's day, was under the administration of women. A girl from the patrician classes could learn several languages (Cleopatra spoke nine, including Hebrew, Greek and Troglodyte according to Plutarch). An Egyptian daughter – thrashed like a boy if she failed to progress – could study philosophy and algebra. She knew the world was round. She understood the value of pi. She could run a business.

Alexandria's greatest gift to a beautiful young ruler – so Schiff argues – may have been a lesson in the power of pageantry. Long before the birth of the Roman triumphs, fabulous displays allowed Cleopatra to glorify herself, demonstrating a close connection to Egypt's gods. It is in her creation of these extraordinary performances that Schiff herself excels. When she describes Cleopatra and Caesar floating down the Nile, she places her readers along the banks of the great river, sharing the experience of the countryfolk who beheld – as was intended – "a sort of magical apparition from another world, the earthly visitation of two living gods."

Pageantry came to the queen's rescue once again when, following Caesar's assassination and her own hasty flight to Alexandria, she needed to reassert her power over Egypt. Intelligence glitters through her adroit yoking of current events to the mythical past, she presented herself as Isis, gathering up the butchered fragments of her consort Osiris (Caesar) to fashion a new heir (her little Roman son). A sibling Ptolemy, her co-regent, was briskly dispatched: poisoning was an art in which the legend-makers did not exaggerate Cleopatra's competence.

Pageantry, most famously, enabled Cleopatra, in 42BC, to control events, when she sailed into Tarsus in the guise of Venus, on a boat manned by a bevy of attendant nymphs. Her prey, Mark Antony, swallowed the bait. He stayed hooked because, as Schiff explains, his dreams of eastern conquests could only be funded by Egypt's treasure. Cleopatra's one miscalculation was in supposing that Caesar's grandson, Octavian (who had cannily betrothed his sister to Antony in order to bind him to Rome's interests), would prove equally susceptible. Pageantry and seductive techniques had no effect upon a man who craved only one thing from Egypt: her wealth. In 30BC, following the deaths of Cleopatra and Antony, Octavian obtained it.

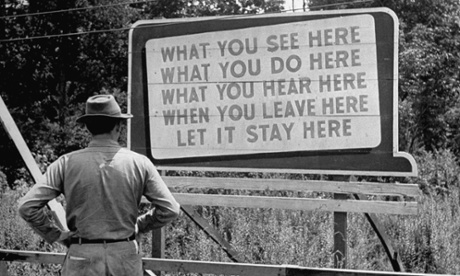

Mystery has never ceased to cloak Cleopatra – always adding to her enchantment. Schiff proves brilliant at peeling away the layers of myth in which earlier storytellers shrouded the Egyptian queen. Did a calculating sorceress distract and unman a great Roman general – or did Cleopatra inspire her lover by her courage and resourcefulness? Did she, following Antony's bungled suicide, envenom herself with the – sluggish – asp, or did she smuggle a swifter, drabber poison into her treasure-piled mausoleum?

Much, despite Schiff's formidable and spellbinding achievement, still remains open to question. But most readers will end by agreeing with Montaigne that, whenever history has presented death as the preferred option, few have embraced it with such voluptuous style as the last of the Ptolemys.

Miranda Seymour's Chaplin's Girl: The Life and Loves of Virginia Cherrill is published by Pocket Books.

• This article was amended on 24 January to correct the picture caption to credit the correct artist.