O black and unknown bards of long ago,

How came your lips to touch the sacred fire?

How, in your darkness, did you come to know

The power and beauty of the minstrels' lyre?

Who first from midst his bonds lifted his eyes?

Who first from out the still watch, lone and long,

Feeling the ancient faith of prophets rise

Within his dark-kept soul, burst into song?

This wonderful poem from 1917 by James Weldon Johnson, "O Black and Unknown Bards", always reminds me of Ellen Gallagher's paintings. Toni Morrison once said that all the future is in the past. Gallagher's extraordinary work explores the near and the distant past. She is an artist who is always looking at time, and what time has done to people. Her work is characterised by a density of imagery and complex, built-up surface detail. It embraces the world of history, fantasy and myth; Gallagher is interested in transformation, mutability, metamorphosis.

Born in 1965, the daughter of a Cape Verdian father and an Irish mother, she studied creative writing before changing to fine art. She chose to spend one semester aboard a huge schooner studying oceanography, and she became fascinated by pteropods - wing-footed water snails that flutter through the ocean mainly at night. She studied them under the microscope and drew them. She enjoyed it so much that she gave up creative writing to attend the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

Her new exhibition, Coral Cities, has just opened at Tate Liverpool and features a series of drawings, collectively titled Watery Ecstatic, and a number of 16mm films. Gallagher explores the idea of a black Atlantis: she imagines all the drowned people, thrown overboard, lost at sea, somehow still underwater. The descendants of enslaved Africans, they now populate the twilight zone of the sea. They've become almost a marine species, half human, half fish.

They are a fantasy created out of a historical reality. They are the descendants of those who were thrown off the slave ship Zong; perhaps the ones who were tossed into the sea because they had the flux or dysentery, or because they were rebellious or even sulky. (John Newton recorded in his captain's log a terrible litany of the dead: "Buried a woman slave no 47 of sulkiness.")

Ellen Gallagher has said: "Some losses are irretrievable." Yet, through her art, she is attempting to go down to the ocean bed and retrieve the lost, like a deep-sea diver trawling the ocean floor for survivors. "I'm interested in reactivating the static," Gallagher says. Her sea dwellers are of that time, but also of this time; the paintings make you think what would have become of the people. Gallagher, in creating them - to borrow a line from Toni Morrison's Beloved - has "understood the source of the outrage as well as the source of light".

The original idea of the black Atlantis that Gallagher calls Drexciya was inspired by the eponymous Detroit house band's 1997 album The Quest, which held Drexciyans to be a marine species descended from pregnant enslaved Africans who had been picked up in west Africa and were heading across the Atlantic to America.

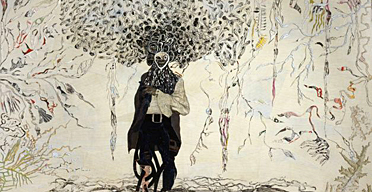

She began the drawings for this exhibition in 2001 - some of the series has been shown in America, as well as in Edinburgh in 2004. The works include a staggering new painting, Bird in Hand, dominated by a black sailor or pirate from Cape Verde, who is part tree, part root. His head is a huge afro made up of other heads; his head seems to contain all of the dead. The afro is made of tiny bits of postwar images from the magazines Ebony and Sepia, which morph into what looks like a shoal of jellyfish or plankton forms. Beneath him are roots, which suggest that the dead have roots in the living - they continue somehow, and are not forgotten. He is entangled; his body could be the body of a tree, perhaps the one his ancestors were tied to when they were whipped. Surrounding him is the odd and surreal ephemera of the sea - fish skeletons, human bones, odd beaks. Another work, Dirty O's (2006), is painted in watercolour, with a collage applied over it: a series of faces with an O forming around their heads, as if there was something they wanted to say.

The Watery Ecstatic works make you think of language itself, the beginning of time, the very first utterances. Coral Cities reminds you how dehumanising slavery was to African people, how the experience repeated itself over time. These faces are the missing faces and found faces. They are faces distorted by racism and stereotypes. They are cultural mirrors, period mirrors, circus distorting mirrors. They are Gallagher's people - true and fantastic, real and surreal, from the not-so-distant past, and possibly from the future. Some of Gallagher's missing people and creatures are disturbing; others fascinating - all of them draw her viewers into a world where they can freely examine their own fears, prejudices and perceptions.

Using the language of modernist painting, Gallagher's work is part natural history and part unnatural history. Something about the way that the underwater people have transformed is oddly healing. Somehow or other, they have survived. Her huge fish are brilliantly accurate. We imagine that they might belong to her tree-bound sailor, they might be part of the pirate's collection. There's a large jellyfish, very beautiful in greens and vibrant pinks. There's a bright green eel. She has created the opalescence on the scales of fish by adding crushed mica (a mineral that was once used in windowpanes) to the water. In this exhibition, she has also explored the history of Cape Verde and the gathering of salt, the white gold upon which the islands' communities were built.

A large, just-completed watercolour depicts a series of women's heads along the bottom. Their hair is metamorphosing into sea plants and sea creatures. The work has been made by cutting into the paper. Along the top is a series of carp, which recall Japanese art. There's a frieze effect: the drowned women thrown overboard have become underwater souls of the sea.

"She is formally and thematically incredibly intricate and dense," says Tanya Barson, curator of the Tate exhibition of Gallagher's work. "There's a wealth of virtuoso detail in the drawing, painting and collage that makes it rewarding to examine. The work we are showing treats slavery in a poetic way; the use of symbolism and metaphor is highly imaginative and sophisticated."

Her work is like jazz on a huge canvas. She paints riffs, repetitions and refrains. Trauma is presented in patterns, repeated cycles, virus-shapes. Freud described anxiety as, on the one hand, an expectation of a trauma and, on the other, a repetition of it in a mitigated form. Gallagher's paintings are mitigated forms. She has always been concerned with what is seen and what is not seen; fascinated by what is framed and what is outside the frame. Including even herself. "What I like about painting is that you have this theatre where you are not there," she has said. "The audience for painting rolls in whenever they like. It's a different relationship to time."

Gallagher's work invites us to think about the people who have gone before her: poets, novelists, artists, musicians, dancers, singers. Bessie Smith is there, eating a pig's foot and knocking back a gin. So are Langston Hughes and Bert Williams, as well as all the unnamed black people lost at sea or lost from history. She is a sophisticatedly literate painter, and her narratives of the deep tell complex, mythical stories. They bring to mind Virgina Woolf's The Waves, where Neville says: "There is an order in this world; there are distinctions, there are differences in this world, upon whose verge I step. For this is only a beginning." In Melville's Moby-Dick, Gallagher asks, why were sailors making these obsessive, miniature carvings on whale ships in the middle of nowhere, looking for this huge monster?

To over-simplify Gallagher's work is to somehow reduce its power. There is no one way to look at a Gallagher painting. Her work has nothing to do with race; it has everything to do with race. Whether the audience is black or white, her work reminds us of ways of seeing. Looking at her earlier work Double Natural, I remembered a time when I'd turned up at school aged 13 wearing a blonde wig. Double Natural is a 5m-long canvas. To make it, she took scores of advertisements for hair straightening and skin lightening from Ebony and Sepia, and arranged them in a grid. She then reworked these ads with yellow and white paint. The women who reappear remade and reactivated by Gallagher are shocking and also extremely witty. The wig is a major motif in her work. She notes that in the 30s, wigs were called transformations. Here the wigs are bright yellow. They make you think of Pecola Breedlove in Toni Morrison's The Bluest Eye, who describes another character as a high yellow dream girl; or of Bessie Smith's "I ain't no high yellow, I'm just a beginner brown", in Young Woman's Blues. It's funny; it makes the idea that black women should ever have wanted to be white, or light, funny, too. "These are not corrective works," says Gallagher.

The work is slow and labour-intensive. "Hard to find a day where you can say you have achieved a lot," Gallagher says. "All I've done today is draw one ear of a hamster." But then she enjoys the pressure of working against the clock, right up to the deadline. She is a true artist, an original thinker - perceptive, witty and very modern (one of her paintings is called Bling Bling). Coral Cities will make your soul sing. Gallagher's work is a whole, densely imagined world. Go and see her, people.

· Coral Cities is at Tate Liverpool until August 27. Details: 0151 702 7400