In Berlin, history and politics dart across your path at every turn. This extends to musical life too. The headline event of Daniel Barenboim's Festtage, the annual spring festival organised by the Berlin State Opera, was an arresting new production of Wagner's Tannhäuser by the German choreographer Sasha Waltz, stunningly performed by a star cast led by Peter Seiffert.

Barenboim, at Waltz's request, used the Venusberg ballet music of the 1860/61 Paris edition, combined with the original Dresden score of 1845. In whichever version, Wagner's sprawling exploration of flesh versus spirit contains some of his most potent music. Stand-alone numbers, such as Wolfram's celebrated Song to the Evening Star, had not yet given way to the through-composed structures of his mature works.

The one important point to know about its complex chronology, however, is that Wagner had been working on Tristan und Isolde in the intervening years. The new Venusberg music for Tannhäuser, in its languid, extreme chromatic richness, epitomised sexual satiety to an even greater degree, with more excessive freedom, than anything found in Tristan. No wonder Baudelaire, as well as Wilde's Dorian Gray, fell upon this tale of a medieval troubadour as the ultimate hymn to decadence.

Last week the promise of a near-naked bacchanal at the start – dancers in none too concealing body stockings tumbling like bugs to the lowest rim of the open-ended cupola which represented the Mount of Venus – had whetted Berliner appetites. One of the first to hurry into the foyer of the Schiller theatre, the company's temporary base while its Unter den Linden home is rebuilt, was a tiny, bright-eyed 100-year-old.

His identity, rather than his grand age, are of interest here. Hans Pischner, a virtuoso harpsichordist and musicologist, was one of the most powerful cultural commissars in the GDR period. He was intendant of the Staatsoper for two decades in the last years of a divided Germany, frequently caught in the crossfire of obedience, conservatism and experiment. "He was very controversial, close to the state and all that that entails," a Berlin opera insider said, as Pischner walked past us. "But now? Hey, he's an old man of a hundred."

Pischner's influence was not merely local. Indirectly he changed the shape of opera throughout Europe and America. He supported Ruth Berghaus, the East German choreographer and director who pioneered the updated or abstract productions now known as "Regietheater" – director's theatre. Hated by the GDR but adored by the west, not least our own English National Opera in productions by David Alden and others, this style now holds sway. Pischner might be proud that Berghaus's 1968 Barber of Seville is still in the Staastoper repertory, receiving its 350th performance just a few weeks ago. The mix of old and new still looks modern.

For Tannhäuser, Waltz opted for a simple updating to the 1950s – particularly echoing the wood-panelled Schiller theatre which was built in that decade. Odd though the prancing Thuringian knights looked in tweeds and jodhpurs, nothing was too obtrusive. The dance, mostly independent of the action, was some of the most sympathetic – that is, non-distracting – I have seen in opera. Act 2, the Hall of Song in the Wartburg, looked particularly handsome, with floor-to-ceiling wood swinging like a bamboo screen. The sight, and sound, of 12 horn players striding across the bare stage was thrilling.

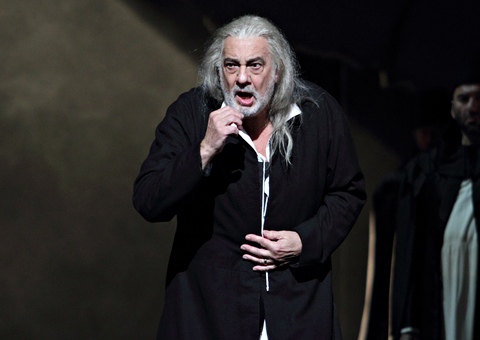

This relatively low-key approach provided an ideal vessel for the music, in a performance hard to fault. Peter Seiffert, the Heldentenor who recorded the role with Barenboim in 2001, retains a ferocious vocal strength, rarely tiring and never forcing the sound. He carried off the Venusberg love-in rather impressively, looking like a teddy bear among the svelte dancers, and clutching any limb, male or female, that came his way. Marina Prudenskaya's Venus was properly voluptuous and musically secure.

Ann Petersen as the virginal Elisabeth, splendid in an Ava Gardner-style satin gown, showed the intelligence and strong-mindedness of a role that can seem merely prudish, making up for some unevenness of tone. René Pape shone as the Landgraf, but the loudest applause, with reason, went to Peter Mattei as Wolfram. The mix of beauty of sound and an ability to act, using silent movie gestures with great expressivity, was as good as it gets.

Barenboim, who had conducted the Vienna Philharmonic in Mozart's three final symphonies – from memory – the previous night in the Philharmonie, drawing fresh, noble playing from this finest of orchestras, was in his element. His interpretation never sounded mannered or interventionist (this was true, which may surprise some, in the Mozart too), tempi were steady but never dragged and, from where I was sitting, the orchestra never drowned the singers. The cheers went on for 15 minutes.

Less than 24 hours later, Barenboim was back again to conduct Plácido Domingo in a revival of Verdi's Simon Boccanegra, rather too safely directed by Federico Tiezzi with plenty of Italianate gothic gold and doge's palace ornamentation. The interest, as ever with Domingo, was to see how he has grown into the role, his voice now sounding more genuinely baritone than when he made the switch from tenor. If there were a few bumps musically, the score not always flowing as freely as it should, Domingo's performance more than made up.

To watch this artist grow gracefully into old age, vocally and physically, is a privilege. Next season, Barenboim will celebrate his friend and mentor Pierre Boulez at 90. Why Boulez? Because, Barenboim said at a press conference the morning after Boccanegra – no doubt his idea of relaxation – "Pierre has always encouraged the public to listen in a more unconventional way". As usual, Barenboim came up with a provocative point of view that made us think.

Star ratings (out of 5)

Tannhäuser ****

Simon Boccanegra ***