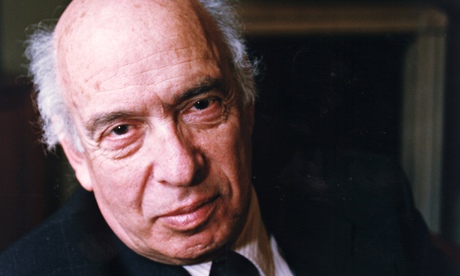

Claus Moser, Lord Moser, the government statistician and former chairman of the Royal Opera House, who has died aged 92, could have become a professional musician, but he chose academia, and academic honours were thrust upon him. Later, banking and business claimed him too, but his passion for the arts underpinned the many roles he undertook with a quick mind and dedication.

His cultured Jewish parents, Lotte and Ernest, had to flee to Britain from Berlin with their two sons in 1936 to escape Nazi persecution. Claus thrived at Frensham Heights school, in Farnham, Surrey, where his musical talents were quickly recognised; he joined the choir and played the piano in a quartet. In 1940 he was given a place at the London School of Economics, but with the fall of France, he was interned at Huyton Camp, Liverpool, along with hundreds of other “friendly enemy aliens”, many of whom, like him, went on to have distinguished careers in their adopted country.

It was there, he said, that his vocation crystallised. “If you put 5,000 Jews behind barbed wire we will all find something to do,” he told the Guardian in 2007. “We counted the number of internees, who they were and what they did. I discovered a love of numbers. That’s how I became a statistician.” He was released in time to take up his place at the LSE and graduated with first-class honours. He then joined the RAF.

In 1946 he returned to the LSE as an assistant lecturer in statistics and in 1961 became professor of social statistics. While at the LSE he was, from 1961 until 1964, statistical consultant to the Robbins Committee on Higher Education and then took charge of the Higher Education Unit set up to continue the work of the committee. His association with Lionel Robbins on the committee and at the LSE led to a lifelong friendship.

Although German was his mother tongue he had a literary gift that enabled him to explain complex ideas in good, simple English. Appointed CBE in 1965, as opportunities opened before him, he gained in self-confidence and overcame much of his shyness. “Worrying is in one’s genes,” he said. “I got it from my mother.”

Moser left the LSE in 1967 to become director of the Central Statistical Office (now Office for National Statistics) and head of the Government Statistical Service. The appointment was inspired, for he had the capacity to carry through a much needed major reorganisation of the service, as well as the knowledge and imagination to develop social statistics, which had been seriously neglected over the years.

It was his vision that established in 1971 a major pioneering study, the General Household Survey, which gathers data every year about Britons’ domestic arrangements, and it was his inspiration that lay behind the publication of the Central Statistical Office’s esteemed annual publication, Social Trends. At the same time he both consolidated and developed economic statistics, showing a firm grasp of what was needed to put economic forecasting on a sounder basis. He served through the governments of Harold Wilson, Edward Heath and Jim Callaghan, and was knighted in 1973.

During these years he studied how those in the Whitehall corridors of power won arguments and manipulated others and gained the self-assurance that stood in him good stead when, in his 50s, he was increasingly called upon to chair arts and other organisations, including the Royal Statistical Society, the Economist Intelligence Unit, and the British Association for the Advancement of Science, where he campaigned for stronger links between science and the arts.

When he left the civil service in 1978, he followed in his father’s footstep and became a banker, joining NM Rothschild and Sons as a director and vice-chairman. In 1984 he happily returned to academic life as warden of Wadham College, Oxford, where he helped to put the finances of the college on a sound footing and, with the help of funds from Japan, began a new building. He had always enjoyed working with young people and before long he knew every student by name. This keen interest in education once again showed itself in the setting up in 1991 of the National Commission on Education which reported in 1995. Throughout his career he was visiting professor at many universities in Britain and he was also an academic governor of the Technion – the Israel Institute of Technology – in Haifa. In 1986 he was appointed chancellor of the University of Keele.

When he was obliged to retire from Wadham at the age of 70, he became chairman for 10 years of the British Museum Development Trust, where he oversaw the raising of £100m for improvements that culminated on 6 December 2000 in the opening of the award-winning Great Court, designed by Foster and Partners.

The task that gave him the greatest pleasure, however, was acting as chairman of the Royal Opera House, an appointment he held from 1974-1987. He had been a member of the board since 1964 and together with his wife, Mary (nee Oxlin), whom he met at the LSE and married in 1949, he grasped the opportunity to visit Covent Garden night after night to see and hear the operas he loved so much. But these were tempestuous times at the opera house. Arts institutions large and small were hit by cuts by successive governments led by Margaret Thatcher, there were clashes with the unions as difficult decisions were made, and artistic standards fluctuated to the delight of the opera house’s critics. Just before leaving Covent Garden in 1987, he oversaw the appointment of Jeremy Isaacs as general director and successor to Sir John Tooley.

On his retirement, the ROH staged a performance in his honour of Le Nozze di Figaro, the Mozart opera that in his 1989 appearance on BBC Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs he chose as his favourite piece. Throughout his career he played the piano, performing at LSE concerts. At Wadham he made many contacts with Japanese students and it was with pride and pleasure that, in 1995, he played a Mozart concerto with musicians from Tokyo, putting in with customary stamina the hours of practice essential to bring off a polished public performance.

He served on the governing body of the Royal Academy of Music, the BBC Music Advisory Committee and the board of the London Philharmonic Orchestra. His love of chamber music dated back to early childhood and musical evenings at home in Berlin. He was a devoted follower of the Amadeus Quartet and, after the ensemble disbanded in 1987, was a member of the board of the Amadeus Scholarship Fund, which supported young string quartet players.

Witty, charming and sociable, he loved good company, while moving mainly in establishment circles of a wealthy and powerful elite. “Claus is about seven or eight people,” said one contemporary, a founder and chairman of Granada television, Denis Forman, in a discussion with the Guardian in 2007, “most of them very agreeable. The central territory of his personality is the arts. He believes in them as others believe in religion. His triumph is in getting people to do things for him.”

Moser had the ability to make people feel at their ease, but he had little time for small talk and unless they could engage and hold his attention he would quickly lose interest. However he numbered among his friends many from his early life, and he and Mary were among the first to offer succour and support should any of them be in grave trouble.

He became a follower of the Social Democratic party when it was first formed, but later reverted to Labour. In his later years he was a devoted supporter of many Jewish organisations. He was made a life peer in 2001. “Claus felt an overwhelming debt to this country,” said Sir David Attenborough, a close friend. “British society saved him. His life has been about paying it back.”

He is survived by Mary, and their son and two daughters.

Muriel Nissel

Jeremy Isaacs writes: Claus Moser succeeded Lord Drogheda as chairman of the Royal Opera House – a hard act to follow. He took great pride in the role, assiduous in attending performances, getting to know the staff, responsive to their concerns. Financially things were hard. The constant reduction of state subsidy, eroded by inflation, left him and John Tooley, the general director, with an almost impossible task: to maintain the house’s international status while keeping ticket prices within the means of regular opera and ballet lovers.

The grant to the ROH was one third of that available to the Garnier in Paris, a fifth of that to La Scala, and to the Staatsoper in Vienna. Balancing the books was ferociously difficult. Board meetings debated wage increases of one or even half a percent. He kept going and, just, succeeded. After his tenure, it transpired that ROH ticket prices over 15 years had failed to keep pace with the cost of a bottle of milk, a pint of beer, a packet of cigarettes, or Cup Final tickets. That was owing to his belief that the best should be available to all.

Claus was ever courteous and caring. Aiming high, in choosing a successor to Colin Davis as music director, he rejoiced in landing Bernard Haitink. I owe him deep gratitude for appointing me to the board of ROH, encouraging me to apply to be general director and opening up a source of unending pleasure.

• Claus Adolf Moser, Lord Moser, statistician, educationist, banker and arts administrator, born 24 November 1922; died 4 September 2015

• Muriel Nissel died in 2010

• This article was amended on 7 September 2015. Lord Moser returned to the LSE as an assistant lecturer in statistics in 1946, not 1943, and served during the governments of Wilson, Heath and Callaghan, not as part of them. It was further amended on 8 September 2015. Lord Moser came to Britain as a child in 1936, not 1935.