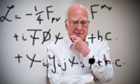

Jack Steinberger, who has died aged 99, was one of the three winners of the Nobel prize for physics in 1988 for their work with neutrinos and the discovery of the muon-neutrino. This research did much to advance understanding of fundamental particles.

The reality of the ghostly neutrino was not confirmed experimentally until 1956, but back in 1948, working at the University of Chicago, Steinberger had first given indirect hints of its presence in his measurement of decays of the muon – a heavy sibling of the electron. He showed that when a muon converts into an electron, two very light, possibly massless, electrically neutral particles are also produced. These, it was later shown, are neutrinos.

With his demonstration that the muon did not decay by the more direct route of radiating a photon, Steinberger had unwittingly also given the first clue that a muon is not simply a heavy version of the electron but has some intrinsic “muon flavour”. What that “flavour” is remains a mystery, but it has become a staple of modern particle physics theory.

Soon theorists suspected that the two neutrinos produced in the muon decay could not be identical. The idea emerged that there are two flavours of neutrino: the “electron-neutrino” with affinity for the electron, and its sibling the “muon-neutrino”, analogously paired with the muon. The experimental proof of this fundamental key to the pattern of fundamental particles came in 1962 thanks to Steinberger and his colleagues Melvin Schwartz and Leon Lederman.

At Brookhaven National Laboratory on Long Island, New York, the trio developed techniques for producing intense beams of high energy neutrinos. At high energies, the chance of neutrinos interacting with material targets increases to a level that makes them experimentally viable. Their breakthrough inspired decades of experimental work involving neutrinos, and their first experiment with high energy neutrinos confirmed the distinctive identities of the electron-neutrino and muon-neutrino.

In essence, there were two ways of producing neutrinos, one where they emerge in association with a muon, another where they come with an electron. According to the theory, the former are muon-neutrinos, the latter electron-neutrinos. What Steinberger and his colleagues discovered was that when beams of the former variety – muon-neutrinos – hit targets and picked up electric charge, the charge was invariably carried by a muon, whereas in the other case, the charge was carried by an electron.

This confirmed that neutrinos carry a memory of their birth, some metaphorical DNA that is passed on to progeny in subsequent interactions. This DNA analogue is known as “flavour” and became a key property in the modern Standard Model of fundamental particles.

He was born Hans Jakob Steinberger in Bad Kissingen, a Bavarian spa settlement in Germany, the son of May and Ludwig Steinberger. His father, a teacher from the town’s small Jewish community, had been a veteran of the German army in the first world war, but with the rise of the Nazis the Steinberger family had no future in their country. In 1934 Hans and his older brother headed for the US, sponsored by an American organisation that had volunteered to bring 300 Jewish children to the country. The rest of the family joined them a year later.

His parents subsequently ran a delicatessen in Winnetka, Illinois, where Jack – as he was known after his arrival in the US – attended New Trier high school and what was then the Armour Institute of Technology, Chicago, before entering the University of Chicago. There he gained a chemistry degree and made a computation of the lifetime of the electrically neutral pi meson, which later played a significant role in the development of theoretical particle physics. Nonetheless, Steinberger felt he was not good enough to shine at theory, and instead focused on experiments. During the second world war he worked on the development of radar in the radiation laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, before returning to Chicago to study physics under Enrico Fermi, gaining his doctorate in 1948.

He then went to the University of California at Berkeley for a year but left because, though not a communist, he refused on principle to sign a loyalty oath attesting to the fact. He moved to Columbia University, New York, joining the faculty in 1950 and eventually becoming a full professor there. He left Columbia to take up a post at the European centre for particle physics, Cern, in Geneva, in 1968.

In 1988 Steinberger was one of the prime movers behind the Aleph collaboration of more than 300 physicists working at Cern’s electron-positron collider, LEP, then under construction. LEP was specially designed to produce the massive Z boson, which is a key agent in the weak nuclear force and is also a portal into studying neutrinos. From the precision measurements of the Z boson’s properties came proof that there are not two but three – and no more than three – varieties of lightweight neutrinos. In so doing, particle physics established a modern analogue of Dmitri Mendeleev’s periodic table of the elements, whose capstone, the Higgs boson, was discovered in 2012.

Steinberger never forgot his reception in the US as a refugee. He donated his Nobel prize medal to his old school, noting that its “good beginning was one of several important privileges in my life”.

He remained active in research and was a regular presence at Cern lectures into his 90s.

His first marriage, to Joan Beauregard, ended in divorce, after which he married Cynthia Alff, a biologist. He is survived by his four children, two from each marriage.

• Jack Steinberger, physicist, born 25 May 1921; died 12 December 2020

• This article was amended on 22 January 2021 to correct details of Jack Steinberger’s early years.