“Comets, importing change of times and states, brandish your crystal tresses in the sky,” Shakespeare wrote in Henry VI, Part 1, in a nod to the age-old belief in the divine influence of the small, icy bodies.

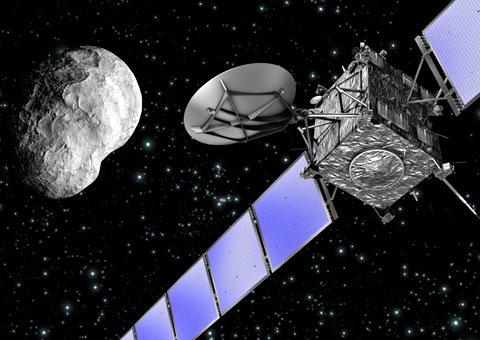

When the Rosetta spacecraft touches down on the surface of its chosen chunk of dust, ice and rock on Friday, it will mark the end of the mission that has dispelled the cloud of mystery and superstition that has surrounded comets for millennia.

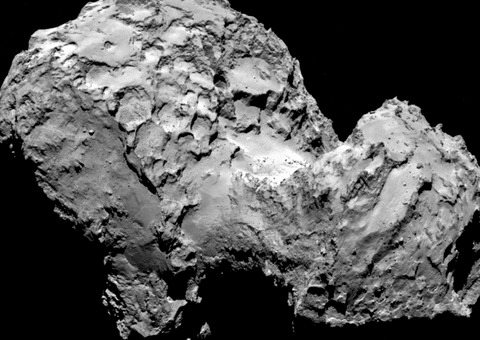

Since the craft arrived at 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko in August 2014, the $1bn European Space Agency (ESA) mission has revealed what comets look like (sometimes duck-shaped), what they’re made of and that - far from being portents of doom - comets helped seed life on Earth.

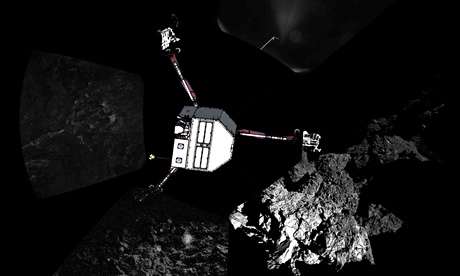

But it was probably the sheer audacity of attempting to land Rosetta’s tiny robotic probe, Philae, on an irregular lump of dust, ice and rock 405m kilometres (252m miles) from Earth, that won the world over two years ago.

“Rosetta has been comparable to the moon landing,” said Andrea Accomazzo, ESA’s spacecraft operations manager. “It’s that order of magnitude. As a child, I could only have dreamt something like this. It’s interesting to see how many emotions landing on a comet still triggers in very many people.”

Comet 67P is now heading out towards the orbit of Jupiter, and as it speeds away from the sun, Rosetta’s solar power supply is flagging, leaving the craft with only enough energy for one final manoeuvre.

Late on Thursday, Accomazzo and his team at ESA headquarters in Darmstadt in western Germany placed Rosetta on a collision course with the “head” of the comet, aiming for a region marked by pits, “goosebump” structures and jets of gas.

In the final moments of its descent, around noon on Friday (BST), Rosetta will train its cameras on 67P and take its last image around 15 metres from the surface, before (hopefully) softly touching down and switching off its transmitter. About 40 minutes later, mission control will receive the last close-up photograph of 67P. Then radio silence will mark the end of Rosetta’s 12-and-a-half year voyage through space.

Mission controllers will never be certain of the probe’s fate, but are aiming for a gentle landing that will leave it resting on the surface. “We could have abandoned it in space or let it bounce off the comet and just switched it off. It wouldn’t have created any problem,” said Accomazzo. “Landing it is more a psychological thing.”

As scientists switch their attention away from the delicate task of controlling a very distant spacecraft to analysing its data, some of Rosetta’s most impressive findings may lie in the future. It has already provided some remarkable insights.

An early surprise was simply the appearance of 67P – the comet’s “dirty snowball” nickname had led even scientists to expect something more bland and uniform in appearance.

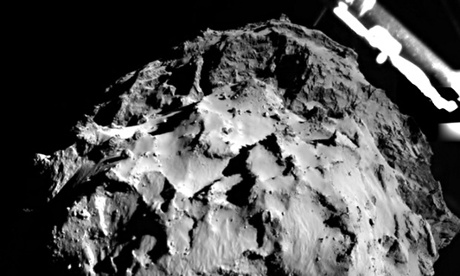

Professor Monica Grady, a space scientist at the Open University who works on Ptolemy, one of Philae’s gas and dust detectors, recalls being “knocked out” by the first detailed surface imagery. “You’d expect them to be dusty and eroded, not these startling landscapes,” she said. “You try to interpret things in terms of what we know on Earth, like glaciers or river valleys, but that’s just not happened on the comet. We need to work out how these landscapes formed. And certainly no one expected it to be duck-shaped.”

Björn Davidsson, a Rosetta scientist based at Nasa’s jet propulsion laboratory, said the mission had revealed 67P was extremely porous, with around 70% of its volume being empty space. “When you see these beautiful images of the comet you should not think of it as rock,” he said. “It’s something like spun sugar or cotton candy – something very, very fluffy.”

Mission scientists were also caught off-guard by jets of dust from the comet, so vigorous that at one stage Rosetta’s star trackers, which help it navigate, were “blinded” and the craft had to be moved away to a safe distance.

Understanding the composition of comets gives scientists a snapshot of the materials that were blowing around in the clouds of dust and gas from which the planets in our solar system formed around 4.6bn years ago. Comets have essentially been in a deep freeze ever since, making them valuable time capsules.

Joel Parker, who works on Rosetta’s Alice instrument, an ultraviolet spectrograph, said: “Comets formed in the cold frozen wastelands of the outer solar system. They’re the remnants of the early solar system that didn’t get to form into planets.”

Before Rosetta, scientists speculated that comets may have delivered up to half the water on Earth during the heavy bombardment 4bn years ago, when comets and asteroids rained down onto the Earth’s surface (the rest of the water being released from the Earth’s interior).

However, measurements of 67P showed that its ice has a much higher fraction of deuterium – a heavy form of hydrogen – than water found on Earth. Scientists regard the heavy water ratio as a kind of astronomical fingerprint.

Gerhard Schwehm, Rosetta’s former mission manager, said: “It now looks like comets weren’t the objects that brought water to Earth, or not the main objects at least.”

Observations of the fuzzy cloud of dust and gas – the “coma” – that envelops 67P, have also revealed traces of the chemical building blocks of life. The findings support the notion that comets delivered some necessary ingredients for life to Earth, and also allow scientists to re-imagine exactly which chemicals were being stirred into the mix.

The Rosina instrument, a mass spectrometer on board Rosetta, detected the amino acid glycine, as well as the chemicals from which it is formed, methylamine and ethylamine. It also found phosphorus, a key component of DNA.

“This is what must have been in the primordial soup,” said Schwehm.

Schwehm, who has worked on the mission since its inception, said ESA’s original plan had been to bring comet samples back to Earth, but this was eventually deemed too expensive and risky. “We decided if we could not get the comet to the laboratory, we’d get the laboratory to the comet,” he said. “Surprisingly, it worked.”

The mission has not been without hair-raising moments for those involved.

For Accomazzo, nerves peaked when Rosetta’s internal hardware tripped and rebooted as it came out of a three-year period in hibernation mode in early 2014, causing a 15-minute delay in scientists receiving the craft’s “phone home” confirmation that it was still alive. Despite knowing that all the technical groundwork had been laid, he admits thinking: “This is crazy, how can this thing fly for three years on its own through space?”

For Grady, the highlight was the Philae landing, in November 2014, when footage of the eminent space scientist whooping and eventually weeping with joy went viral on Twitter. Aside from the birth of her son, she admits, “nothing is ever going to top that”.

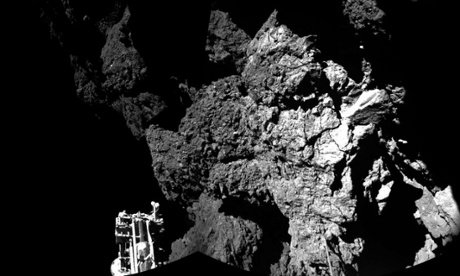

After the initial celebrations, mission scientists later realised that Philae had bounced across the surface before coming to land in a shady spot beneath a cliff. Philae’s batteries drained within a couple of days and, after briefly waking up again a couple of times as the comet approached the sun, it was never heard from again.

Despite things not going entirely to plan, Grady estimates that Philae still carried out 80-85% of the work it was scheduled to do. And in a moment that mission scientists described as “emotional closure”, Rosetta finally managed to spot the washing machine-sized lander on the surface earlier this month.

As dust settles on the Rosetta craft – assuming the landing goes to plan – mission scientists are holding a celebratory barbecue to avoid things getting too maudlin.

“It will be very sad”, Grady said. “It’s been a big part of our lives for such a long time.” she adds. “In six years, the comet will be back again. We won’t be able to speak to it, but you’ll be able to look up and know Rosetta’s a bit closer to us.”

Professor Mark McCaughrean, the senior science advisor at the ESA, told BBC Radio 4 it was a sad day as he reflected on what the Rosetta mission had achieved

“It’s giving us a real insight into the building blocks of the solar system and the material which could have formed life on the earth, not life itself but the raw building blocks,” he said.

“But more importantly for me, it’s engaged the public in a way which is just unparalleled for a robotics space mission. The enthusiasm I see on the faces of kids around the world when I give talks and the public following online it’s going to be very sad day but a very proud day for everyone that’s been involved.”