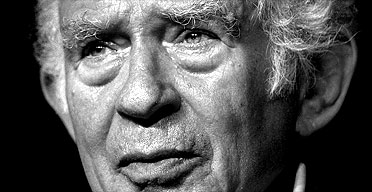

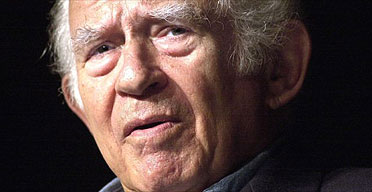

The term "literary lion" could have been invented to fit the American writer Norman Mailer, who has died aged 84 of acute renal failure. He relished confrontation, and was often at his most impressive in the public arena. However, underneath the lion lurked a clumsy cub, and among Mailer's many appealing attributes was his talent for play.

He led a double life as a literary artist, being both novelist and journalist, addressing himself to the issues of his times, from feminism to consumerism - "Plastics," Mailer replied when asked to designate the modern world's main enemy - space travel to birth control, Vietnam to race riots, the psychology of the mass murderer to that of the graffiti artist.

Gaining an idea of his range requires sampling from all over the vast table of his output. But if there is a "best" book from the more than 40, it is perhaps The Executioner's Song (1979) in which he fused his two careers by writing a "non-fiction novel" based on the life of the murderer Gary Gilmore, executed in 1977, the first person to suffer the death penalty in the US after a four-year moratorium. That book showed Mailer to be capable of controlling a style of lyrical simplicity, whereas his reputation had been built on baroque, complex sentences, fizzing with ideas to the point of genius or idiocy.

Though intending to send up a fireworks display, Mailer was unafraid of the damp squib, and often pricked his grand ego with bathos. Describing his meeting with the poet Robert Lowell in The Armies of the Night (1968), Mailer related how Lowell called him "the best journalist in America". He had been hoping the poet might have said "best writer"; but Lowell's assessment was nearer the truth.

Mailer was born in Long Branch, New Jersey, and given the middle name Malech, because, as his mother explained: "Malech is 'king' in Hebrew, and he was our king." (The name on the birth certificate reads "Kingsley".) His parents' families had come to the US from Russia, by way of South Africa, where his father was born; during this passage the name Mailer was forged from a Russian original that Norman never knew. His father, Isaac, was an accountant, and his mother, Fanny, ran a housekeeping and nursing agency. The family moved to Brooklyn when he was four, and after attending local schools he entered Harvard to study aeronautical engineering in 1939.

At university, however, he began to see himself as a writer, and shortly after graduation in 1943 was presented with a subject: the second world war. Eighteen months in the Pacific with the 112th Cavalry, seeing "modest bits of action", according to his own account, but rising only to the rank of sergeant technician, which actually meant first cook, provided the material for The Naked and the Dead, published in 1948 to great acclaim for the 25-year-old author.

Mailer could fairly assert he had been both cursed and blessed by early success, but he was mostly blessed. The struggle, as is often the way with precocious artists, was to come later in life, when he was unpredictable in his choice of subject (Ancient Egypt, the life of Christ, Picasso) for books that were either too fat or too thin. At the end of the 1940s, though, he could enjoy being number one on the bestseller list, and indulge himself in the frivolous thought that The Naked and the Dead was "possibly the greatest book written since War and Peace". It was nowhere near it, of course (as he knew), but it did give him a career.

Next Mailer wrote two more novels, Barbary Shore (1951) and The Deer Park (1955), which failed to consolidate his critical triumph. By then, however, he was living the life of a grown-up writer: he had worked in Hollywood, had got married (to Beatrice Silverman), and followed in the wake of the writers of the Lost Generation (Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Dos Passos) by going to Paris. Several contemporaries lived there, including William Styron, Peter Matthiessen and Irwin Shaw (author of The Young Lions, another war novel inevitably compared with War and Peace), but the most potentially valuable friendship Mailer formed was with James Baldwin, himself a proven novelist and journalist, though settled in a lower league than Mailer. They met at the house of Mailer's French translator, Jean Malaquais, at precisely the time that Mailer was developing his theories on blackness and "hip", which were to result in the essay The White Negro (1957), and Hipster and Beatnik, appended to it in Advertisements for Myself (1959).

Baldwin, sensitive, frail, gay, took an immediate liking to the brash Mailer, portraying him fondly in his wonderful essay on their relationship, The Black Boy Looks at the White Boy, as "confident, boastful, exuberant, and loving - striding through the soft Paris nights like a gladiator". But when it came to jazz, the nature of "hip" and the psycho-pathology of the "White Negro", Baldwin grew weary: "The Negro jazz musicians among whom we sometimes found ourselves, who really liked Norman, did not for an instant consider him as being even remotely 'hip'."

Mailer was well practised in the art of devastating judgments himself, of course. The trigger for Baldwin's put-down had been the publication of Advertisements for Myself, which included a section entitled Quick and Expensive Comments on the Talent in the Room. Styron had "compromised himself"; Bellow wrote "in a style I find self-willed ... I cannot take him seriously"; Kerouac lacked "discipline, intelligence, honesty". There were no talented women writers at all, and as for Baldwin, be was "incapable of saying 'F--- you' to the reader".

By the late 1950s, Mailer was drinking from a wild cocktail of ideas involving violence, cancer, sex, birth control, the use of drugs. Stories about his fighting filled the gossip columns: headbutting contests at parties; boxing round a startled John Updike met by accident in the street; punching Gore Vidal. He liked the company of boxers, trainers and fight journalists (the light-heavyweight champion, José Torres, was a particular friend), and wrote well on the subject. The physical assertiveness contrasted with a relatively short stature. But Mailer was upright and broad, with a mane of ever-greying hair and a liking for safari shirts, as if the life of a man of action was never far away.

His most famous boxing essay is the book-length account of the Ali-Foreman Rumble in the Jungle, The Fight (1975), but his best is the 30,000-word piece (originally published in Esquire) on the 1962 Liston-Paterson bout, which lasted one round, Ten Thousand Words a Minute. At a news conference, Mailer sat down in Sonny Liston's chair and refused to move when the boxer arrived.

The violent antics had had far more serious consequences two years earlier, when Mailer stabbed his second wife, Adele Morales, puncturing her cardiac sac and necessitating emergency surgery. At this stage, friends regarded him as being on the verge of dementia, and his explanation that he stabbed Adele "to relieve her of cancer" does little to contradict the view. In 1962, Mailer divorced Adele and married Lady Jeanne Campbell, daughter of the 11th Duke of Argyll. The marriage lasted only a year, and, in 1963, he married Beverly Bentley, an actor.

His egomania began to find a more conventional outlet, in politics, though he chose an unconventional form in which to express it. Advertisements for Myself had been, as the title suggests, a mainly self-reflective collection, comprising stories, play fragments, opinions and interviews. His next assemblage, The Presidential Papers (1963), was meant as a source of counsel for John F Kennedy, a man whom Mailer considered capable of uniting the entire American people in a revolution of consciousness, as Martin Luther King had united the black population. Kennedy might even be the first "hipster" president.

Here again, the pen jabbed at the salient topics of the day - Cuba, juvenile delinquency, the Red menace - interspersing essays with letters to the president. ("Wasn't there anyone around to give you the lecture on Cuba? Don't you understand the enormity of your mistake - you invade a country without understanding its music.") More collections of the same type followed: Cannibals and Christians (1966), Existential Errands (1972) and Pieces and Pontifications (1982). The last, as Mailer wrote in a preface, contained remarks on "marriage, sex, pornography, God, the Devil, rock, science, magic, violence, art, literary status, women's liberation, male identity, and even ... occasional comment on the craft of writing".

In his own writing, he had tried not to put fiction in second place behind journalism. But the solitude needed for reflection and attention to craft was the one thing the king of the literary jungle could not command. Mailer's prose in his novels, on the whole, lacks suppleness and classical disinterest: he cannot help muscling in on his characters and forcing his own views on them. His fiction after the mid-1950s is seldom based on character for its own sake, which would entail modest attributes; Mailer's fictional creations are making as much noise as they can. Between 1955 and 1979, he wrote only two novels, An American Dream (1965) and Why Are We in Vietnam? (1967). The latter is not a story of the war itself, but consists mainly of the recollections of DJ, Disc Jockey to the World, on a hunting trip to Alaska two years before. At this time, too, Mailer sank a lot of money into a film project, Maidstone (1970), in which the writer-director takes the part of "Norman Kingsley, movie director" and runs for president. It gave no financial, and little critical, return.

In 1969, he was a real-life, if quixotic, candidate for mayor of New York, on a "left conservative" platform urging that the city become the 51st state, while its "black ghetto dwellers" should vote on getting their own government. Later, he directed a screen version of his own novel, Tough Guys Don't Dance (1984), and took the role of Stanford White in the film of EL Doctorow's Ragtime (1981).

Something Mailer did better than writing novels was to apply the techniques of fiction to a non-fiction subject. The first book to use this strategy was The Armies of the Night (subtitled History as a Novel/The Novel as History), which recorded, through the eyes of the narrator, "Mailer", the 1967 march on the Pentagon to protest against the Vietnam War. He employed the same technique in other books, including Miami and the Siege of Chicago (1968) and Of a Fire on the Moon (1970), an account of space travel in which he styled himself Aquarius.

The novel was still the contest for which the big awards were given, however - no one was likely to win the Nobel prize for writing journalism, though Mailer still had hopes - and to say that Mailer's talent was not suited to fiction was the quickest way to hurt him. He managed to prove his critics both right and wrong at the same time, then, by producing, in 1979, his 1,000-page-long non-fiction novel, The Executioner's Song. It traces the story of Gilmore from his childhood, through a life of petty crime, to the cold-blooded murders of a petrol-station attendant and a motel manager, to his weird apotheosis when he pleaded for the appeals process to be halted so that he could be executed by firing squad. It was a grisly drama of the modern Wild West that seemed to be waiting for Mailer's shaping skills, and he tackled it at the top of his form.

Even this feat, though, was hampered by grandiose ambition. The second half of the book is given over to the peddling of Gilmore's story as a news-media event (Mailer himself never met the murderer), which has the effect of leaving The Executioner's Song broken-backed. It was another instance of the 50% rule in Mailer's life, according to which everything could seem half-brilliant and half-dud; the genius was always matched by the clown.

Many potential readers must have been put off by the clowning and the belligerence. "When two men pass one another in the street and say 'Good morning'," he once said, "there's a winner and a loser." And it was a characteristic inseparable from his skill at playing the news-media game, which kept him to the fore of the cultural stage for more than half a century.

On at least one occasion after the stabbing of Adele, his twin fascination for violence and publicity led to something more serious than a tiff with Liston. In 1981, a prisoner serving life for murder, Jack Abbott, was released on parole following a correspondence with Mailer. Abbott represented the kind of Dostoyevskian conundrum Mailer dreamt of: a psychopath too "pure" to live in society. With Mailer's help, Abbott published a collection of writings, entitled In the Belly of the Beast, which does indeed contain some startling prose, but within a few weeks he had stabbed to death a young waiter in a Manhattan restaurant, and was soon back inside.

What could Mailer offer, by way of vindication? "Culture's worth a little risk," he told a press conference, at which point a reporter from the New York Post asked: "Specifically, what elements of society are you willing to risk? Waiters?" Later, Mailer admitted: "People who say that I have blood on my hands are right. I do."

The prodigious flow of words did not cease with age, but sometimes his choice of subject matter left old admirers scratching their heads. His huge novel of ancient Egypt, Ancient Evenings (1983), puzzled those that had seen him as above all a chronicler of the American present. Two books of the following decade, Harlot's Ghost (1991), about the CIA, and Oswald's Tale (1995), a return to his earlier interest in Kennedy, were praised for many qualities, but fell foul of their own unwieldiness; one is seldom charmed by a book that is hard to lift. In 1997, he succeeded in causing another news-media storm by writing a novel about Christ, The Gospel According to the Son. Newspapers in Britain ran news stories to cover the brouhaha, in which Mailer denied that he identified with the Son of God.

Taken less seriously by literary critics, he was increasingly a celebrity, which, for him, had always been half the point. In the middle of the fuss over The Gospel, he popped up as a commentator in a film documentary about the Rumble In the Jungle, When We Were Kings, a character as full of charm, intelligence and humour as one could wish to meet. Which, indeed, was how he usually was in person. His aggrandising machismo was matched by a generosity of spirit, a willingness to share ideas and help younger writers. In New York in 1989 I requested a meeting to talk about Baldwin, for the biography I was then preparing. Mailer arranged drinks at the Algonquin, and spoke with affection for his old friend, attributing to him more "pure talent" than any of their generation. I was grateful not only for his insights, but for the feeling that Mailer had thought about what was required.

His dedication to his job was borne out in The Spooky Art: Some Thoughts on Writing (2003), assembled when he was 80: "Over the years, I've found one rule ... If you tell yourself you are going to be at your desk tomorrow, you are by that declaration asking your unconscious to prepare the material. You are, in effect, contracting to pick up such valuables at a given time. Count on me, you are saying to a few forces below: I will be there to write. The point is that you have to maintain trustworthy relations."

Those relations served him well to the end: February of this year saw the publication of The Castle in the Forest - from Walderschloss, the name given to the Dachau concentration camp by its inmates - a novel of nearly 500 pages inquiring into the nature of evil. This account of how dark forces infected the family of an Austrian customs inspector, Alois Schicklgruber, later Hitler, and his son Adolf, points to the impossibility of attributing total blame for the most barbaric acts to any one individual.

In 1980, the lion had married yet again, Carol Stevens, and then again, Norris Church. Mailer married and divorced Carol on the same day, in order to legitimise their child, and then married Norris the next day. Altogether, he had eight children, and alimony meant that he never lived in lavish style. "You never know a woman till you've had her in court," he quipped. His marriage to Norris was the enduring one, however; Mailer said that when he first set eyes on her, he was so struck with love that he had to leave the room. Their son, John Buffalo, was born in 1978, and both survive him, as do stepson Matthew by an earlier marriage of Norris's, and Mailer's children Susan from his first marriage; Danielle and Elizabeth from his second; Kate from his third; Michael and Stephen from his fourth; and Maggie from his fifth.

Back in the early 1960s, Mailer bought a flat in Brooklyn Heights, overlooking the Manhattan skyline, and stayed there for most of the rest of his life. The living room was done up in strange style, with a ship's rigging and nets. At one stage, the only access to his office was by rope (he explained this oddity by saying that he was terrified of heights). At parties, guests were urged to participate in contests, climbing up and down the ropes, descending, winners and losers alike, to some further sport. The king of Brooklyn Heights enjoyed nothing so much as play, and the second half of the 20th century offered him plenty of scope.

· Norman Kingsley Mailer, writer, born January 31 1923; died November 10 2007

· This article was amended on Wednesday November 14 2007. The murderer Gary Gilmore did not die in the electric chair, as we suggested in the obituary of Norman Mailer. He was executed by firing squad. This has been corrected.