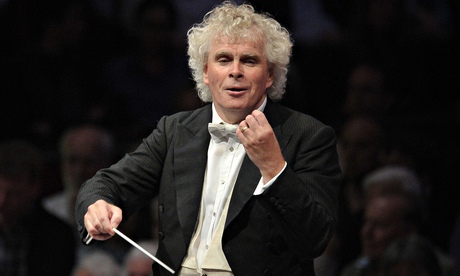

“I don’t think that musicians can change the world … ” Hang on – this is not what Simon Rattle is supposed to say. Of all today’s British conductors, Rattle is the one you would bet on not only contemplating changing the world but actually doing it. The former wunderkind who put Birmingham on the classical music map, he is now the conquering hero returning to the UK after 15 years in charge of the Berlin Philharmonic, which many consider the greatest orchestra in the world.

He continues - “but I do think that musicians can make the world momentarily a better place.” Phew. We are backstage at the Barbican, the London Symphony Orchestra’s home venue, and the more Rattle talks the more it seems clear that he sees “making things better” as not only a possibility but a responsibility.

When he takes up the post of music director at the LSO next month – he will combine this with the Berlin job for a year before leaving the Philharmonic in summer 2018 – he will carry with him an enormous weight of expectation. Teachers dream that his influence might fix the funding crisis in music education. Managers hope this rare household-name conductor will be a shot of adrenaline for the box office. Audiences want to hear that velvety Berlin Phil tone added to the LSO’s already dazzling palette, and the LSO players themselves know that he is likely to be listened to when he insists on good rehearsal time and conditions for his musicians. “He is a game-changer,” says Nicholas Kenyon, managing director of the Barbican Centre and Rattle’s biographer. “He gets music on to the front pages of newspapers; the television cameras follow him. He takes music to a new level.”

Rattle has been accused of being too much of a politician, of talking in soundbites, but it’s more that the words come out in short, sweeping bursts of enthusiasm. He is a galvaniser, an inspirer, and he knows this is a necessary role for a musician in such a public position. After our interview, I watch him giving a two-minute pep talk to a conference of music teachers, and you can practically see them basking in the glow.

There is an air of inevitability about Rattle coming back to the UK to helm its highest-profile orchestra, even if he won’t admit it. He claims the idea of taking on the LSO hadn’t occurred to him until he was in London to guest conduct Wynton Marsalis’s Swing Symphony in July 2012, when an old friend in the orchestra happened to ask, “You wouldn’t just think of coming here and being the boss?” His other performance with the LSO that summer was for the opening ceremony of the London Olympics – remember Mr Bean playing one-finger synth in “Chariots of Fire”? You could argue that the Rattle-LSO brand was already being built up back then.

He is looking forward to getting stuck in. “Of course, the feeling of coming home is important,” he says. “But it was the orchestra’s curiosity and enthusiasm and complete lack of bullshit that I found amazingly attractive. And their rhythmic precision and flexibility and energy are incredible. Because I’ve been so steeped in this very particular Berlin tradition I know that I can also offer them a lot in terms of depth of sound. And there are other areas – they have played no baroque music in recent years, and very little Haydn and Mozart – where I can be of use.”

Rattle is being modest; and as for the LSO, which in the past decade has had eight years of fly-in-fly-out leadership from Valery Gergiev followed by a two-year interregnum, it is positively champing at the bit.

The week we meet, Rattle is in town for two performances with his new orchestra, one of them a community opera with music by Andrew Norman, A Trip to the Moon, involving the massed community choirs of the LSO Discovery scheme. This is the third time in as many years that Rattle has commissioned a gigantic new work for amateurs and professionals together, to be performed in London, Berlin and elsewhere. In Berlin in 2015, the first of these – The Monster in the Maze, composed by Jonathan Dove – took on added resonance as a substantial number of those who signed up were refugees and that the story, based on the Minotaur myth, involved boatloads of young people taking a journey to unknown dangers.

The Berlin Philharmonic’s education department – something it didn’t have until Rattle’s arrival – has been very active in its work with the city’s new arrivals, and so has its conductor. Last spring, Rattle and his orchestra joined Daniel Barenboim and Iván Fischer in a concert at the Philharmonie in Berlin for an audience of refugees and their helpers. “We thought it was necessary for someone to say ‘Welcome’. My assistant, who is running lots of education projects in the camp in Tempelhof, went with one of the refugees from Aleppo, a teacher, into the foyer. And this little boy ran up to them and threw his arms around the teacher – they were both from the same street in Aleppo. Neither of them knew the other was there – and they met in the foyer of the Phil. I had a little weep when I heard that.”

The Philharmonie is home to the Berlin Philharmonic in a way that the Barbican isn’t to the LSO, not quite. Rattle is vocal about the disadvantages of the Barbican: “Everybody does absolutely the best they can, but it’s like running round very fast in a lift; there’s a certain point where the walls and the ceiling are all too close.” The story that he made a new London concert hall a condition of signing his contract with the LSO is not true, but what is remarkable is that it was believable: Why does he have so much clout? “I don’t!” Oh, come on. “It’s because I’ve been away,” he jokes.

But then he turns serious. “When I was in Birmingham it was a very fortuitous time as politicians on both sides of the divide were wanting to make a new city.” Rattle, aged 25, was appointed conductor of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra in 1980, and within three years plans to build Symphony Hall were being drawn up. “The politicians were smart enough to realise that the city needed not only a new image but a new heart and soul. It was made very clear to me that the cultural centre would get built, even if they fought like cats and dogs over everything else.”

The proposed new Centre for Music on the site of the Museum of London got to the stage of a feasibility study before having its government funding withdrawn. “I’m still not sure how much of the emergence of the new concert hall as an idea was simply to do with the rivalry between George Osborne and Boris Johnson,” Rattle says – but the fact that it is no longer the ball in a game of political whiff-whaff makes it if anything more likely to get built. “Now it’s up to us to raise an enormous amount of money. If there was ever a time when it might work, it could be now.” Momentum does seem to be growing; a shortlist of possible architects was announced days after we spoke. But it’s clear that Rattle believes the new building must be a centre for education as well as a concert hall. “This art form is for everybody. It is our job to spread the word, not just to play the music. I said to the orchestra in Berlin, ‘You’ve been fantastic high priests but you now have to be evangelists as well.’”

If education projects are to engage new listeners, he says, they have to be “things that people can do rather than watch”, and concert halls have to change “in the way that most museums have changed – from don’t touch to please touch”.

For the time being, though, Rattle will be doing what he can at the Barbican, and making plans for some big works as one-off events in bigger venues – 2018 will see Stockhausen’s immense, enveloping work Gruppen in the Turbine Hall of Tate Modern. And his Prom this month gives him and the LSO the chance to perform Schoenberg’s colossal Gurrelieder in the Royal Albert Hall, free from the space restrictions of the Barbican.

His title at the LSO will be Music Director – which in itself signals a change from the role taken by his immediate predecessors, who were designated Chief Conductor. What is the difference? “I will be much more involved with the day to day, even though I won’t be living here permanently. This is a proudly independent orchestra, but it’s a matter of having someone taking care – it’s been a long time since they’ve had that.” Not every conductor wants to take on the nitty gritty of an orchestra’s long-term development. “Valery [Gergiev] wasn’t interested, nor Claudio [Abbado]. Colin [Davis] loved them to bits, but he made it very clear that he did not want anything to do with the running or the auditions or the personnel.”

So when did the LSO last have a real caretaker? ‘I suppose it was Andre”, he says – and Previn ended his tenure as principal conductor in 1979.

Rattle will be in London for about four months every year in total, when, he says, “I will absolutely work my ass off for the orchestra and for the arts. And then it will be good to escape. I think if I lived here I would be ‘on’ absolutely every day, and I’m not sure I would survive. Not in my 60s.” Home for the 62-year-old will remain Berlin, where his children are growing up. He and his wife, the Czech mezzo-soprano Magdalena Kožená, have two boys aged 12 and nine, and a three-year-old girl. (He has two grown-up sons from his first marriage.) They live half an hour from the city centre, five minutes from the Grunewald, where a forest walk offers the chance of an encounter with a wild boar, and next to a lake where the children can swim. Family life involves “an awful lot of football and table tennis and trampoline. Or we go down to the local playground, or we make sushi together – it’s really messy but not so difficult if you don’t want it to look gorgeous. And there’s a lot of making sure the tortoises don’t escape from the garden. All they do is sleep, eat and try to escape. We had three.” How many do they have now? He winces. “Two.”

When Rattle took the LSO job – his appointment was announced in March 2015 – he thought he would be travelling between two EU countries. The morning after the referendum he was in London, rehearsing with the LSO. “People were desperately upset. Some of the players asked whether I’d have taken the job if I had known. I said it would have made me extraordinarily wary, it’s true – but we will make the best of it we can. And a lot of our European counterparts have said, ‘We are going to try to do more work with you rather than less!’” With the orchestra, or with Rattle? “Conductors aren’t separate people! We don’t exist without our orchestras.”

You could argue that some of the great conductors have been very separate people indeed, but standing apart is not Rattle’s style: one of his singular talents has been for making musicians and audiences feel that he and they are all in it together. Our interview done, he hops on to the podium to take an open rehearsal of Sibelius’s Symphony No 2, ready for the weekend’s concert. The stage is creaking with a huge orchestra, half seasoned LSO pros and half young Guildhall students. There are no grand pronouncements about how he wants the piece to go – instead, he just raises his baton: “Let’s make some music and see what happens.”

• Rattle and the LSO perform Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder at the Proms on 19 August; the LSO’s new season begins on 14 September with a 10-day festival to mark the arrival of their new music director. alwaysmoving.lso.co.uk.