Black Flag. Minor Threat. Bad Brains. Cro-Mags. Youth of Today. Negative Approach. Simply reciting the names of some of the great hardcore bands gives you a sense of what they are about. Fast, urgent and uncompromising; US hardcore reimagined British punk rock and launched a genre that has coloured – in one way or another – most of independent music since.

Doing it yourself, releasing your own records, driving your own van, booking your own shows and not caring if the major labels were paying attention became the ethos bands lived by and the legacy they left behind. But a cursory look at modern hardcore reveals a genre that – 30-odd years on from its emergence, and 20 since the pop punk bands inspired by hardcore’s first wave became international rock stars – appears to be carving itself yet another niche in music.

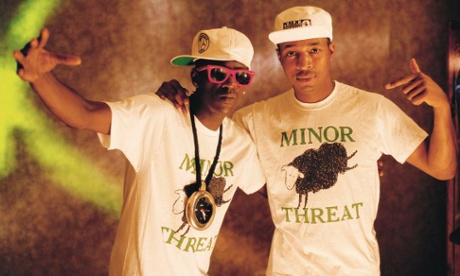

New York’s Cerebral Ballzy provided the soundtrack to Channel 4’s Grand National advert this year with their song On the Run. Fucked Up’s latest album further cemented their position as the critics’ hardcore band of choice, while Sacramento’s Trash Talk teamed up with Odd Future to help shove the circle pit into hip-hop’s lexicon.

But not everything is well at hardcore’s party. Arguably the genre’s most important band – Black Flag – has been engaged in a seemingly never ending civil war after rival factions tried to claim ownership of the name; the official version, led by founder Greg Ginn, released a comeback album that sullied the name of one of the great American bands. One of the genre’s recent younger leading lights, Iceage, have distanced themselves from the sound and seemingly gone country instead. Bands in London and elsewhere are finding it hard to secure gigs because of a lack of affordable venues. But hardcore was forged by the marginalised and disenfranchised, so being pushed to the edges of society isn’t an issue; it’s their natural habitat.

In October 1978, Black Flag released the Nervous Breakdown EP, a four-track, rapid-fire statement of intent that signalled the birth of hardcore. It quickly spread across the US, gaining footholds all over, especially in Washington DC, where groups such as Minor Threat gave it a radical makeover culminating in the straightedge movement. In the mid-west it became even more aggressive, with bands such as Negative Approach creating rock’n’roll out of nihilism. In New York, Cro-Mags provided the brawn and Bad Brains extolled the virtues of violently executed musicianship, while in Austin, Texas, the scene revolved around a militantly leftwing and gay group of bands including the Dicks and MDC (Millions of Dead Cops).

“The first time I heard [the Bad Brains song] Sailin’ On, my mind was completely blown that someone could play that brash and that fast and still be eloquent,” says Cerebral Ballzy frontman Honor Titus. “It was something that defied everything I’d heard up to that point.”

For Peter Shapiro, a US music journalist who was a teenager when hardcore began to take root, the scene was about much more than music. “Because it was American and Americans were doing it, it became a religion and that, for me, is what separates hardcore from anything else. It became a way of life,” he says. “It’s a southern Californian working-class reaction to the general mid-70s vibe, which was very white bread, Stepford Wives, Olivia Newton-John, bottle blondes and easy listening. Reagan summed all that up. He had a blankness and was held up as a kind of John Wayne character and this paradigm of American masculinity.”

But for hardcore bands now, the current White House incumbent isn’t a natural enemy. So instead of aiming at Barack Obama, US bands have increasingly looked inward or to new avenues for bilious inspiration. Joe Galarraga of the Big Ups definitely takes a more navel-gazing approach to songwriting: “I think some of the songs we’re writing now are not as politically focused. Now it’s whatever is weighing on my mind at the time,” he explains. “I’d like to think I stay on top of things and still talk with friends about things like why there’s so much inequality in the world. It’s almost like a sick hobby trying to figure out the roots of these problems and if there is a solution.”

Conor Rickford, the drummer for UK hardcore group Mob Rules, says the same is true of bands here. “The UK bands definitely don’t have the political focus of bands in the 80s. Discharge was all about nuclear war, Thatcher and the Falklands – but it seems that now they don’t have it. That could change quickly but it just seems passé.”

But hardcore is still used as a political instrument in places where national identity is an issue. In Brittany, the Breizh Disorder series of punk compilations is now up to volume nine. In Catalonia, bands such as Destino Final, GLAM and Una Bèstia Incontrolable may not make specific political references in their songs, but singing in Catalan while there are tensions over a possible referendum is a statement in itself, just as it is for the Basque punks Cicatriz who sing in Euskara.

For all that Cerebral Ballzy are getting on TV, and Fucked Up are playing larger and larger halls, hardcore works best when it stays underground. “It doesn’t translate well to being played in massive venues, and it doesn’t translate to good production,” says Rickford. “The recordings have a documentary purpose rather than trying to make a work of art – so it’s not like someone is going to record the White Album or something. It wouldn’t work.”

The restricted parameters of “true” hardcore have always driven the more ambitious acts to express themselves via different mediums. Black Flag challenged their own audience, who wanted faster and faster songs, with their slowed-down sludge-metal instrumentals and spoken-word passages from Henry Rollins. Ian MacKaye had his fill of bellicose machismo with Minor Threat, and eventually drew up the blueprint for alt-rock with Fugazi, who would kiss potential stagedivers back into the audience and condemn slamdancers. Many current-day hardcore bands lead double lives, too. Elias Bender Ronnenfelt of Iceage plays in his lo-fi synth side project Vår; Helm (AKA Luke Younger), the electronica support act on Iceage’s autumn North American tour, is also a member of London hardcore act Lowest Form; Titus moonlights in a shoegaze goth outfit and also recites his own poetry.

“I’ll be the first to admit it’s an aesthetic cul-de-sac: three chords played as fast as you can and you shout over the top of it,” Shapiro says. “I can find universes in that but I understand why as a band you get bored of that pretty quickly.”

However, hardcore itself is diversifying, too. Vast online archives mean that bands are taking influence from rarer hardcore groups, not just the big names. So instead of groups all trying to riff on Bad Brains or emulate Black Flag’s guitar sound, they are just as likely to draw from Italian outliers Cheetah Chrome Motherfuckers or Yugoslavian all-female mid-80s outfit Tozibabe.

It isn’t just vintage hardcore that the bands are drawing on for inspiration, though. The hardcore-in-spirit-but-not-in-sound concept isn’t new – the Minutemen brought a skittish, jazzy take on the genre that often left them drenched in spit by unimpressed hardcore fans – but it’s less of a risk to a group’s safety now than it used to be, and bands that might not sound hardcore but have connections to the scene are being incorporated into harder gigs. In New York, garage rock scuzzers Hank Wood & the Hammerheads are in because they share members with bona fide hardcore band Crazy Spirit, while in Australia post-punk outfit Total Control have kudos because their members also play in StraightJacketNation.

In the UK, Leeds-based indie rockers Eagulls often play hardcore bills with bands such as Autobahn and Perspex Flesh, having cut their teeth playing in skatepunk groups such as Fast Point. “You can tell they’re not an indie band because they’ve got a bit more edge to them,” Rickford says. “Even if it doesn’t come across in the music, it’s the way they present themselves and the way they perform.”

Even if the hardcore scene is accepting of non-hardcore music, it does still have one acceptance problem: its lack of diversity. Although there are successful all-female groups such as Las Otras from Barcelona, KURRAKÄ from Austin, Texas, and the Hysterics from Olympia (who wear their hardcore credentials on their chests, with T-shirts that replace Black Flag’s iconic dark bars with four used tampons), for some the door remains locked. Ashley Holland plays in punk outfits Frau, Personnel and Good Throb, and believes that many in the hardcore scene will never take female musicians seriously. “We don’t play with hardcore bands because they wouldn’t ever consider us. It never crosses their minds that we would fit that bill,” she explains. “I think in the UK scene, women are allowed to be in these twee indie bands but the second a woman is angry it’s a fucking joke and completely off the radar for a lot of the men in our scene, who switch off.”

Although much of the hardcore scene historically sought solidarity with right-on causes – the Dischord label run by MacKaye and its support of domestic violence refuges and gun-control organisations, for example – some of its bands have been less careful about offence. Bad Brains were homophobic for religious reasons; southern California punks Descendents adopted a sexist and homophobic fratboy humour. Agnostic Front and, more recently, Iceage flirted with rightwing imagery. Holland sees the current London Oi! revival – a punk subgenre synonymous with football thuggery and attempted far-right infiltration – as being similarly difficult to swallow. “They don’t realise that with imagery comes connotation and it’s uncomfortable for them not to understand that,” she says. “It harks back to an era that isn’t very comfortable for a lot of people. I think there should be a level of understanding of how that comes across. Especially when you’re playing to a bunch of white people in a very middle-class setting – just have a clue.”

Shapiro says those problems are hardwired into the genre. “Hardcore was a place where you could be different and be accepted and that was pretty rare at the time. But it did help to be different and a white male,” he argues. “Fundamentally, it was 99.9% hypermasculine. It was a scene by and for straight white teenagers and with that you’re definitely going to get homophobia and misogyny.”

But for Titus, such an uncompromising form of music will always confront taboos, however uncomfortable that makes some people. “It’s a style of music that is uncensored and is presented hard and brash. That’s what it is. And, of course, when someone brings you their ideas uncensored; they can be racist, they can be loud, they can be angry, and often those people are male.” The point, he says, is that those things might crop up in hardcore, but they don’t define it.

Hardcore may still be struggling with its own internal politics. But the fact that, more than 30 years on, it is still operating under the radar – with its own support systems, its own networks, its own labels, and new generations of fans still crowding its house shows, basement parties and benefits – proves that music still needs the alternative it offers.