The haunting Last Days opens and closes with a recording of Jancquin's La Guerre, a powerful 14th-century French chorale piece. Resonating with grace, it perfectly bookends Gus Van Sant's spare, empathetic film about the anguish, demise, and resurrection of a Kurt Cobain-like rock star. One can't help but think how this beautiful piece of music will reverberate in the enormous Lumière cinema during its world premiere next week in competition at the Cannes film festival. It will herald the return of the man who won both the Palme d'Or and best director award there for Elephant two years ago.

For Van Sant, the most difficult part of Cannes is the endless round of press interviews. "The rest isn't so stressful, like walking around and walking up the red carpet," the 51-year-old film-maker says. Does he think he can repeat the victory? "I figure we probably won't win," he says. "I try not to put myself in a competitive situation. It's different to doing a long jump, where you focus on getting the most yardage. With a film, it's interpreted through a jury. It's not quite the same as an Olympic event." He does, however, admit to counting the number of palms on the back page of Variety, a rough indicator of achievement awarded daily to competing films by international critics.

Last Days is the last in a trilogy of spare, low-budget independent movies shot in contained settings that began with Gerry (2002) and continued with Elephant (2003). "They're each about death," the Portland, Oregon-based Van Sant says. "Gerry is about death by accident. Elephant is about death by insanity or retribution by someone else's hand. The third is about death by one's own hand." All are derived from real events covered in the media: Gerry, on the death of a youth lost in the desert; Elephant, on the Columbine high school shootings; and Last Days, on the suicide of Cobain, who lived in Seattle, a fellow celebrity artist in America's Pacific north-west.

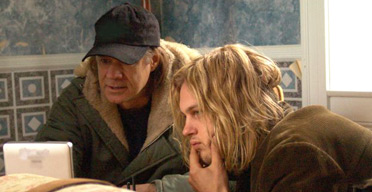

Made with a small cast and crew, Last Days is set in 1994 (the music gives it away) on a large country estate where handsome young rock star Blake (Michael Pitt of The Dreamers and Dawson's Creek) resides with his pals-cum-assistants. Blake, whose white wristband indicates that he has just returned from a clinic or rehab facility, is in a drug stupor throughout (although we never see drugs). He mumbles, makes little sense, and moves in slow motion. He spends his time either alone or fleeing from his housemates (who include Lukas Haas, Asia Argento, and Scott Green), other friends, his manager, a private eye, and a record executive, all of whom want a piece of him. He is most comfortable outdoors. In the house he aims a rifle at his sleeping friends while wearing a woman's black slip and boots. He falls on the floor. He writes, sings, and plays guitar. (Pitt performs two of his own compositions.) He wanders into a rock club in the nearest town. He cooks macaroni and cheese. He ODs in the guest house. In a sublime use of superimposition, he climbs out of his own body. "He's returning home," says Van Sant. "It's like an unwinding of his life." His frightened housemates flee. Attendants arrive to remove the corpse. End of film.

Van Sant began working on the project in the mid-90s. He says that at one point he thought about making a straight biopic of Cobain, and talked to Courtney Love about it. "Courtney was very supportive," he says. But it evolved into something more elliptical and metaphoric, merging with a story he already had about a young boy just trying to fill his time ("I don't even think there was a death," he says now). Around 1996, he says, it took a new direction after the deaths of so many people that meant something to him in such a short space of time.

"I was thinking about people who had died then: Jerry Garcia, Kurt, and River Phoenix," he says. "The papers wrote that they died from drugs. Other things surrounding them were perhaps more intense. The drugs were a form of release rather than a cause of death." In 1997 he published a novel, Pink, which he says helped him work through his grief over Phoenix's accidental overdose in 1993. The two had become close friends after working together on My Own Private Idaho (1991). The death of Cobain, whom he had met only once, had a less personal effect; it was more cultural and geographic.

"I had this feeling that things had been altered in something I felt a part of, the arts movement in the north-west. Cobain died in the winter of 1994. The music scene had become very big in Seattle, with Nirvana being the premier band in the area. With his dying, it closed Nirvana down. Actually, it was sort of ending anyway. Maybe he died because it was ending." Van Sant says that he didn't need to use Nirvana's music in Last Days - something of a blessing in disguise, perhaps, after the difficulties Nick Broomfield experienced in his documentary Kurt & Courtney. But then, Broomfield was an outsider looking for a news story; Van Sant is very much a Seattle insider.

In the film's opening sequence, Blake, wearing some sort of institutional pyjamas, runs through the woods toward a lake, where he ends up standing on a rock wearing only wet boxer shorts. (Van Sant is openly gay and such scenes appear in his work matter-of-factly.) References to the elements - earth, fire, and water - are overt. For the director, this overture is loaded with meaning. "It's like the beginning of the abridged edition of The Golden Bough, a book that I go back to a lot. It has as its theme the deposing of the cult priest leader, who is killed by the upcoming leader. In the first chapter of my edition, a priest lives in the woods near a lake. He is running and hiding in the woods from someone who might come, defeat him, and take over. He fears for his life and tries to defend it."

For the film's large house, Van Sant filmed at Osborn Castle, also known as Castle Rock, in Garrison, New York state, a 45-minute drive from New York City. Now vacant, railroad magnate William Henry Osborn built the stone structure as a summer home in 1881. Like Blake, the building looks good on the exterior but is dilapidated inside. Van Sant says he felt a kinship to the place. When he wrote the original treatment, he was himself living in a big house in Portland. "I bought it with money I made from Drugstore Cowboy. That's what Kurt and Courtney had done in Seattle with money they made. They were living in a basement; then all of a sudden they go buy a big house."

Van Sant has first-hand knowledge of what happens when successful artists and their friend share a residence. "The house becomes a mixture. People who work together form an insular community. It's almost like a frat house, but the dynamics are such that there is a controlling party. There's a posse situation, an entourage." Were the others needy, like Blake's buddies, who ask for cash and help with their own music? "Yeah," he says. "The friends need stuff. Their projects are hatched and need funding."

Things changed outside the home as well. "All of a sudden, you are a source for grant money, or contributions to political campaigns, or film screenings to raise money. You're suddenly enlisted in a world that you weren't part of before. What you had before was just your body." The household split up when Van Sant moved for a time to New York "to a different big house".

Stylistically, Last Days is light years away from such mainstream Van Sant movies as Good Will Hunting (1997) and Finding Forrester (2000). Working closely with his longtime cinematographer Harris Savides, he shot over a period of four weeks in chronological order. Rather than covering themselves with multiple set-ups for each shot, they used only one. Van Sant edited simultaneously - on film, a rarity these days. He recorded natural sounds at the same time as the live songs and occasional dialogue, which he wanted to feel random - "a quality more life-like than story-like". The acting was improvised.

The individual shots are exceptionally intense. For this, he credits Hungarian director Bela Tarr, whose opus Satantango is a leisurely film with very strong imagery in shots of long duration. "Bela pushed me into concentrating on what you're shooting and really try to look at things that are speaking to you from the frame, rather than strategising about how you're going to cut things together. It's basically avoiding cutting in favour of concentrating on what you're shooting." (He says that Tarr also inspired his time loops, the repetition of a scene from a different angle. In Last Days, there are only two such loops, though he used many in Elephant.)

"Viewers can interpret the images, and ultimately the film itself, in many different ways," Van Sant says. "They are participants in what they are watching." Cannes, where the journalists who do those endless interviews can be harsh and vociferous, will be the acid test.

· Last Days premieres at the Cannes film festival next Friday, and goes on general release in the UK in September.