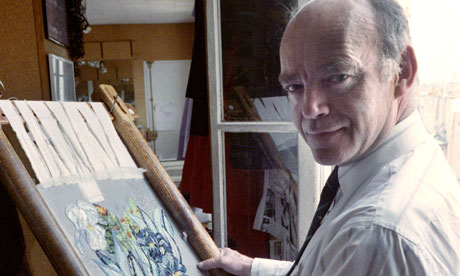

François Lesage, who has died aged 82, used to say that, like his father, Albert, before him, he couldn't reliably thread a needle, let alone sew on a button. But for 60 years he was the head of Maison Lesage, which survived to be the last great embroidery atelier in Paris, so important to couture that Karl Lagerfeld made it his first purchase when, in 2002, on behalf of Chanel, he bought six fashion suppliers to represent the perfect French balance of art and craft.

The firm had been founded in 1868 by Albert Michonet, who worked for Empress Eugénie and her couturier, Charles Frederick Worth. It prospered at first, only to flounder after the first world war in a straitened and aesthetically simplified France. Albert Lesage, a businessman with a talent for fashion, returned to Paris from a venture designing garments for a Chicago department store and bought Michonet out in 1924; he also married Marie-Louise Favot, who had been educated in the decorative arts.

He sketched, she coloured, and together they managed the firm through the boom of the 1920s and the bust of the 1930s, when the company was saved at the last moment by an order for goods from Elsa Schiaparelli. Young François was the workroom pet at the time, some of his childish drawings embroidered for real by indulgent hands.

After the second world war, shortages of luxury goods forced Albert to act as an agent for textiles. Although Christian Dior's 1947 New Look collection, which revived the French luxury industries, did feature embroidery, it was that of Lesage's rival, René Bégué (Rébé). Albert was grooming François to follow him; at 18, he was left in charge of the firm when his parents were briefly away, and created an impromptu design, based on Botticelli's Birth of Venus, for an important Italian customer.

The next year, he was sent to the US to learn English, and was welcomed into Los Angeles by his godmother, Simone Bouvet de Lozier, and the French expatriate community, including the movie star Charles Boyer, who became a mentor in charm. François used the opportunity to pitch his father's embroideries to the Hollywood studios' costume designers, for use on and off the screen. To avoid customs duty, he imported Lesage sketches instead, and to execute them he recruited a Cuban workforce in a new atelier he named, for its location, Lesage-Sunset Boulevard. The enterprise prospered, making gowns for Marlene Dietrich and Lana Turner.

François was soon summoned home, however, when his father fell ill. He took a slow boat to France in 1949, arriving to find his father already dead, his mother the company regent and the family firm struggling.

Through the early 1950s, he carried his mother's suitcases of seasonal samples (produced on spec) through the tradesman's entrances and up the back staircases of the new maisons de couture. Many of Lesage's old patrons were dead or gone, but François found new customers among their replacements, Jacques Fath, Pierre Balmain and Cristóbal Balenciaga, designers who preferred the Lesage approach to the more florid and carbuncled style of Rébé; in time, so did Dior. However, it was the next generation, especially Hubert de Givenchy and Yves Saint Laurent, who really came to appreciate François's California-inspired freshness: playful with fabulous materials, delighting in adding plastic paillettes or metal studs to the traditional repertoire.

In the 1960s, embroidery was unfashionable; but then came the great couture change of the 1970s, when, following Saint Laurent's example, Paris houses began to profit from ready-to-wear, licensing and perfumes, products marketed via the high-concept commercials that are catwalk shows. Labour-intensive heavy embroidery, even more than fantastical fabrics or extreme cuts, became the ideal high-visibility luxury. From the mid-70s onwards, designers visited François in his Montmartre workshop to tell him about their wildest dreams.

Saint Laurent wanted Van Gogh's paintings, impasto and all, transmuted to sequins; Lagerfeld requested that Coco Chanel's Coromandel lacquer screen be mimicked in goldwork; Thierry Mugler asked for a littered beach with discarded bottles done in beads (Tina Turner ordered a version).

François was especially close to Christian Lacroix, the dazzler of the 1980s. Many of that house's most theatrical spectacles, based on Bizet's Carmen or L'Arlésienne, were Lacroix-Lesage co-productions. Lesage-embroidered gowns were not only used for couture publicity and for its perfume advertisements; there were also customers willing to wear (and able to pay for) the garments themselves. It cost $1m for 11,000 woman-hours spent on the cape, gown and train of the 1977 coronation dress of the Central African Empire's Empress Bokassa; $150,000 for 2,500 hours on a wedding dress for a Saudi princess.

François favoured wit over mere sumptuousness: his favourites among the 60,000-plus designs of his lifetime included a trompe l'oeil embroidered copy of Women's Wear Daily, the fashion trade journal, sticking out of a pocket on a Bill Blass suit.

Just as had happened in his father's day, in the early 1990s there came an economic crisis in which the firm's carefully saved postwar profits evaporated. The staff was halved, never to be rehired, since hands just as technically skilled could be hired in the developing world for a fraction of a Parisian salary. In 1993, one of François's four children, Jean-François, opened his own workshop producing embroidery for interiors in Chennai, India, where there were still families in which the craft was hereditary. In the French film Brodeuses (A Common Thread, 2004), a former top hand for Lesage, now scraping by on freelance commissions, is thrilled by a last chance at a Lacroix spectacular.

François responded to the economic realities of the future by investing in the past: he opened a school in 1992 to teach embroidery near his firm's headquarters; he hunted down and bought up what he could of fine, handmade supplies, including 40 tons of antique beads and spangles; and he had 100,000 company designs and samples, dating back to the time of Napoleon III, archived. These unique assets became the property of Chanel after the 2002 buyout, but have remained underused, despite a discreet appearance in the culture ministry-supported Maîtres d'Art shows. François was also unhappy with a recent Chanel plan to move his firm, along with the other five specialists (jeweller Desrues, goldsmith Goossens, milliner Michel, shoemaker Massaro and plumier Lemarié) out to less historical joint premises in the suburbs.

François was made an officer of the Légion d'Honneur in 2007, and given the title Maître d'Art by the French minister of culture. He is survived by his wife and children.

• François Lesage, couture embroidery designer, born 31 March 1929; died 1 December 2011