The "London Whale", Bruno Iksil – the JP Morgan trader who oversaw a catastrophic series of complex bets at its City headquarters, and who was finally harpooned on Friday – is now estimated to have cost his employer $5.8bn and counting.

Mike Cavanagh, the man JP Morgan boss Jamie Dimon put in charge of investigating what went wrong, told investors he had uncovered "numerous embedded risks that this team did not understand and were not equipped to manage".

The mathematical model the bank was using to assess the risks of its almighty bets was, Cavanagh said, "sloppy and incompetent".

At first sight, the whale's costly voyage through the choppy seas of finance appears to be another cautionary tale, after the Libor scandal, about the immoral and reckless behaviour of the banking class. It is: but it can also been seen as compelling new evidence that today's sprawling financial institutions, with balance sheets the size of countries, have simply become too big and complex to manage or regulate effectively.

As its website says, "JP Morgan is a leader in asset management, investment banking, private banking, treasury and securities services, and commercial banking". In other words, like its global rivals, including Barclays and RBS, it tries to do everything from investing granny's nest egg to brokering giant corporate takeovers and inventing fearsomely complex new ways of staking its clients' money.

Before the whale surfaced, Dimon was widely regarded as one of the shrewdest players on Wall Street. But Cavanagh's blunt assessment was that the hefty bets on credit derivatives that JP Morgan's chief investment office had got itself into were simply too complicated to understand or control.

The chief executive can set the tone for his staff – in Bob Diamond's case at Barclays, one of reckless swagger. But he can barely be expected to understand, let alone contain, the actions of individual trading desks.

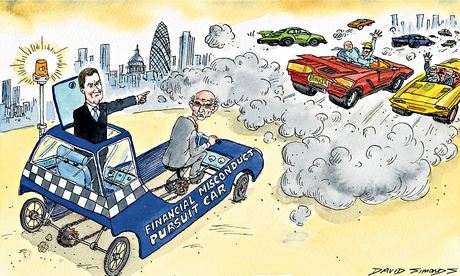

Even those within the banks whose job is to measure and curtail risks are forced to rely on the kinds of mathematical models that were shown up during the sub-prime crisis as deeply flawed. And if that goes for the traders and their bosses, including JP Morgan's chief investment officer Ina Drew, who quit after the scandal first emerged, it must also surely apply to the regulators given the impossible task of keeping the banks in check.

Part of the reason JP Morgan was forced to restate its first-quarter results last week was that the financial instruments in the whale's portfolio, much like the bundles of sub-prime loans at the heart of the credit crisis, were all but impossible to value. And this, ironically, was in a branch of the bank whose job was partly to hedge against risks on behalf of the wider organisation. In fact, Iksil was taking such huge bets on a little-known index known as CDX IG 9 that he was distorting the entire market.

The fact that many banks had been allowed to become "too big to fail" was one of the major lessons policymakers took away from the tumultuous events of 2008 and 2009, when taxpayers around the world paid such a heavy price for preventing the financial system from collapsing.

Ever since, they have focused on equipping regulators with new powers, and trying to insulate ordinary savers' deposits from the banks' riskiest activities, through the much-amended Volcker rule in the US, and the Vickers reforms in the UK.

Yet none of this tackles the mighty power of banks that remain too big to fail, too dominant across too many markets to offer genuine competition to savers, and – as Dimon's failure to hunt down the whale ultimately shows – too big to manage.

Buckles now has little security at G4S

Asked by the New Statesman in April this year to sum up his leadership style in three words, G4S chief executive Nick Buckles replied: "No excuses, please." It was a line entirely in tune with the polished corporate image that G4S is a hard-driving, top-performing services company that delivers on its promises.

Yes, there have been cock-ups over the years – escaping prisoners and so on – but they tended to be isolated incidents. The difference with last week's Olympics bungle is that it comes down to bad planning by central management. Announcing two weeks before the event that you haven't been able to recruit enough security guards is a reputation-wrecker.

It should be said that Buckles hasn't tried to offer lame excuses. But that's because the failure is inexcusable. The contract to supply 10,400 guards for the games is large – the biggest mobilisation of civilians since the second world war, it is said – but G4S knew what it was taking on. It knew the timetable, it knew the drop-out rate for applicants and it knew and the slack it had to build into its processes.

It may turn out that the Home Office was foolish to write a contract with "just in time" clauses in an attempt to reduce costs. Ultimately, though, G4S was on the hook to deliver the contract it signed.

Buckles, as the man at the top, seems highly unlikely to survive the shambles. His credit with his own shareholders was already low after last year's failed attempt to buy Danish rival ISS for £5.2bn, a deal that died almost the moment it was announced – it knocked 20% off G4S's share price. Concentrate on running the empire you've already built, shareholders told him. It was good advice, since employing 657,000 people in 125 countries was already presenting logistical headaches, as we now see.

There seems little point in forcing out Buckles immediately, since his time in the next six weeks is probably best spent trying to rectify matters (and next week's appearance before the home affairs select committee is an unnecessary distraction). But it's hard to imagine him in his post come the Christmas re-runs of the sporting highlights.

More of the same in Spain

Just a fortnight has passed since the Brussels summit when Spain claimed to have wrung crucial concessions from the formerly immovable Frau Merkel.

Spain would be given an extra year to meet its deficit targets, and allowed to receive rescue funds directly into its clapped-out banking sector without the ignominy of a full-blown bailout.

But the briefest glance at Mariano Rajoy's latest budget cuts, announced last week and worth an extraordinary €65bn over two years, should be enough to disabuse anyone who thought the cult of austerity was waning in the eurozone.

Rajoy may have avoided the humiliation of a team of inspectors from the International Monetary Fund picking over his policies, but analysts pointed out that the harsh package, including a VAT rise and swingeing cuts in local government, was almost exactly what they would have prescribed.

As Dario Perkins of Lombard Street Research put it last week: "Just when you fear sense and pragmatism might prevail, European policymakers resort to type and order is restored."