This rambunctious reworking of Cervantes’s Don Quixote judders between inland America and downturn Britain, euphoria and grief, picaresque and satire, postcolonial melancholia and posthuman futurism – often on the same page. It’s a novel less to be read than to be scrolled through, a seemingly endless feed of gags, thought spasms and larger-than-life happenings. Life itself, a character claims, has become:

a series of vanishing photographs, posted every day, gone the next. One had no story any more. Character, narrative, history, were all dead. Only the flat caricature of the instant remained, and that was what one was judged by.

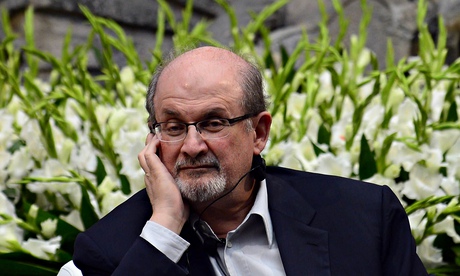

Rushdie’s earlier novels, among them Midnight’s Children and Shame, were heralded as antidotes to the beige provincialism of much British fiction in the 1970s and early 80s. They were noisy and antic. They slalomed through history, philosophy, imperial politics. They dramatised hybridity, interconnection and cultural convergence. They were populated by absurd, hysterical, grotesque characters. They seemed alive to the modern world. And now? What happens when much of modern life seems like a grotesque noisescape?

Quichotte, which has been longlisted for the Booker prize, abounds with exuberantly broad-brush characters. Foremost among them is Ismail Smile, a travelling salesman “of Indian origin, advancing years, and retreating mental powers”, who journeys across the US to meet his beloved Salma R. She’s a bipolar former Bollywood star who has decamped to New York where she has reinvented herself as a daytime TV presenter. Smile is accompanied by a son named Sancho who describes himself as “black-and-white in a full-colour universe”. For both Smile and Sancho are fictional, the inventions of Sam DuChamp, an Indian-born author of unsuccessful spy thrillers who is also struggling to deal with a lot of what might best be summarised as “family shit”.

Sam, or Brother, fell out with his sister, known as Sister, years earlier, after he learned she was having a secret affair with the Sad-Faced Older Painter. She escaped India and set about becoming a prominent radical lawyer in London. Now, faced with cancer, she is increasingly falling foul of community leaders and spokespeople. She believes in free expression and the rule of law as foundations for free society:

This was the kind of remark you didn’t make too often in white society in London for fear of sounding self-righteous, ‘preachy.’ It was also a remark which, if made in brown or black circles, might elicit a loud series of disbelieving horse-laughs.

Other figures skitter through the novel. There’s RK Smile, Ismail’s wealthy cousin and an Indian community philanthropist who makes his fortune by flooding the US with opioids. Billionaire Evel Cent, a florid futurologist presumably based on Elon Musk, bangs on about parallel space-time continuums and the need to create new homes for mankind. This is, as the narrator says, “the Age of Anything-Can-Happen”, an age in which “nothing was reliable, treachery was everywhere, identities were slippery and mutable, democracy was corruptible”. Also making appearances: Hans Christian Andersen (who gives Ismail romantic advice), angry mastodons, Italian talking crickets, speaking revolvers. Anything can happen, but that doesn’t mean readers will care. In fact, readers may care less when settings keep shifting and the story keeps jumping like a video game full of cheat codes. Mutability is one of Rushdie’s enduring themes. His novels are about migrants who shed skins, assume new guises, shift and sway with the times. These transformations may be cons and deceptions, but they are also existentially creative. In Quichotte, he defends his roaming, sometimes befuddling storytelling:

It may be argued that stories should not sprawl in this way ... yet so many of today’s stories are and must be of this plural, sprawling kind, because a kind of nuclear fission has taken place in human lives and relations, families have been divided.

But he also seems to hanker for a centre that can hold, worrying that fiction and cyberwar are two sides of the same coin, representing:

the pollution of the real by the unreal, of fact by fiction. It was the erosion and devaluation of the empirical intellect and its replacement by confirmations of previously held prejudices.

This is not uninteresting territory for a writer to delve into, but Quichotte is too restless and in love with itself to be anything other than a symptom of the malaise it laments.

It’s spattered with Wiki-like chunklets of history (on the 18th-century black British writer Ignatius Sancho, on early-20th-century Indian immigration to America) and semi-comic riffs (on the difference between field hockey and ice hockey, on how Douglas Adams’s death after visiting a California gym proves that exercise is overrated). Some – including an ode to the Dutch actor Robert Wolders, who was in relationships with older stars such as Merle Oberon and Audrey Hepburn – are entertaining. More often they are linguistic readymades, clunky old anecdotes, the stuff of late-night chat shows.

Bombastic and busy, always in control even when his story is meant to be spiralling out of control, in this novel Rushdie resembles a highbrow Robin Williams. Rarely does he give readers time to breathe. Often he spells out things that don’t need to be spelled out. At one point, he redundantly describes Quichotte as “a tale about obsessional love”, coming across not so much as a classical storyteller as a slightly patronising TV presenter. He has a fondness for sweeping generalisations (we live in “the age of the invented name”; this is “the generation of Netflix-and-chill”) and descriptive shortcuts (an important character is compared to the actor Frank Langella; the effectiveness of a drug is likened to “a first genuine orgasm after years of being Meg Ryan in Katz’s Delicatessen”).

This is lazy writing for lazy readers, eyeball-grabbing anti-prose for distracted device-users. It makes his attempts to craft more contemplative or lyrical passages particularly jarring. Time is said to be “that lethal chamber of horrors whose walls close slowly in upon the luckless inhabitant until they crush the life out of him”; to be beaten up is to realise that what made you a human being “could come loose from the world, as if the self were a small boat and the rope mooring it to the dock slid off its cleats so that the dinghy drifted out helplessly into the middle of the pond”. One character endures a batch of medical tests – so many that doctors “bombarded him as if he were a Syrian refugee enclave”.

A self-consciously literary lineage, gobbets of magic realism, shards of metafiction: Quichotte, like all Rushdie’s novels, will trigger a minor landslide of academic criticism. It anticipates and even longs for it, authorsplaining “the picaresque tradition, its episodic nature, and how the episodes of such a work could encompass many manners, high and low, fabulist and commonplace”.

There are occasions when it has the bounce and merriment of a bon vivant raconteur rattling off anecdotes at a dinner table. There are fewer occasions when it’s possible to care about the trajectories of the characters, or to believe the author is that bothered by “the destructive, mind-numbing junk culture of his time”. In the end, it mimics rather than offers an antidote to the “flat caricature of the instant” that it says it laments.

• Quichotte is published by Jonathan Cape (£20). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £15, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99.