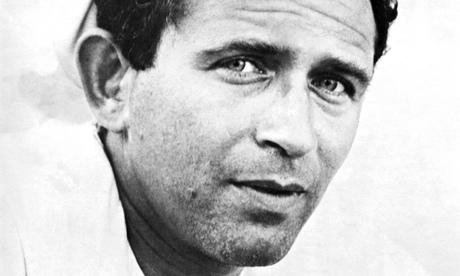

Seven years have passed since the death of Norman Mailer, and a campaign is being waged in his name on several fronts. The publication late last year of J Michael Lennon’s authorised biography asked us to contemplate what its title referred to as a double life. A series of Random House reissues shifts attention to the essays and novels. With the release of the selected letters the most congenial approach to Mailer is illuminated: one in which the works and days are understood as marching, like his “armies of the night”, in lockstep. If John Updike’s larger body of work somehow seems a less of a vertiginous challenge than Mailer’s 44 books, it is because Updike’s chief legacy is his style: the profusion of opiate sentences that delivers us hit after euphoric hit. Mailer bequeathed us no style. What he wanted to do was to save our souls, and that was a battle to be fought in a variety of guises: General Marijuana, Aquarius, the Prisoner, and, of course, the Great Illeist – someone who refers to themselves in the third person – Norman Mailer himself. Selected Letters of Norman Mailer grants us access to the dressing room.

Lennon’s role as custodian of Mailer’s literary estate may seem redundant: after all, acting as his own curator was part of Mailer’s addiction to self‑dramatisation. Commencing with the taming and recontextualisation of the juvenilia and marginalia in 1959’s Advertisements for Myself, he was determined to frame his own works and set the parameters within which they were to be considered. However, his executor’s pruning proves indispensable: having given himself over to the fanatical labour of making a selection from more than 45,000 letters, Lennon presents us with 716 key missives, dating from 1940 to Mailer’s death in 2007.

Reviewing The Essential Norman Mailer (non-canonical and thrown together for a quick buck) in 1982, Martin Amis wrote: “No one in the history of the written word, not even William McGonagall or Spike Milligan or DH Lawrence, is so wide open to damaging quotation.” Or, indeed, to damaging anecdote: at that time precisely Mailer was still in correspondence with Jack Henry Abbott, the murderer-turned-author whose parole he’d supported a year previously, despite the fact that Abbott had killed again only six weeks after his release. Amid the subsequent pummelling of Mailer’s own credibility, he yet had some counsel for the reincarcerated: “Get it through your head, Jack, that any media representative, if they want to fuck you, have more opportunities than a prison guard, and to pour out your heart and say what you think to a media representative whom you have not checked out from asshole to appetite is equal to a pretty boy stepping into a tank for the first time and saying, ‘Gee, do any of you fellows have a light?’”

But Mailer was always able to wrestle something out of the wreckage of a bad situation. The astonishing essays on theatre and cinema (collected in 1972’s Existential Errands and now begging for reissue) were the autopsies of his misfired and misbegotten efforts to revolutionise those disciplines. Likewise, following the Abbott fiasco he was able to apply his enriched perceptions to other feats of imaginative empathy. That quality distinguishes his unblinking portrayals of two other murderers: Gary Gilmore and Lee Harvey Oswald.

This empathy is of a piece with an aggressive amour-propre rooted in and justified by his particular notion of “existentialism”, here recast as a ceaseless oversight of a fragile yet demanding inner self, one continually threatened by indolence and compromise. A 1961 letter to writer Don Carpenter reveals our quick-change artist considering his options at the lexical boutique: “I got so sick of ‘hip’ and ‘square’ as words that from now on they’re out. I mean, let’s start something new. Existentialism is the word we have to use now as in ‘That’s very E–X, man, very E–X.’ Squares will now be called essentialists, as in ‘That’s very E–S, man, straight 8.’” While Mailer never ran with the essentialism tag, what we do witness is the birth of a lifelong love affair with a word: “existentialism” would remain his catch-all, encompassing the transformative experiences of prison, bullfighting, good and bad sex, and a hell of a lot more besides. If this elastic usage cuts us adrift from the term’s usual meaning, it is because his route to it had “almost nothing to do with any formal existentialism” (to David E Gerard, 1963). What really alerted him to the possibilities for existentialism in the novel was his encounter with EM Forster’s insight that “character can dissolve in one stricken event and re-form in startling new fashion”.

For “Norman Mailer” – that is, the character who first appears in The Armies of the Night – the “stricken event” occurred in 1948 with the publication of The Naked and the Dead, the success of which acted like a lobotomy on the writer’s past and demanded the hasty forging of a new psyche and persona to face a wildly different reality. “It was as if there was somebody named Norman Mailer, but to meet him people had to meet me first,” as he put it in Advertisements. The Brooklyn kid, Harvard alumnus and Pacific veteran found that sudden fame forced him to recalibrate his conception of authenticity, for his new life had nothing to offer him with either the scale or the intensity of his wartime experiences. A brief flirtation with Trotskyism and a stint as a Hollywood scribe-for-hire proved dead ends: Barbary Shore and The Deer Park were savaged by the critics. By this point something has vanished from Mailer’s letters. What makes the correspondence predating The Naked and the Dead so thrilling – and what it evokes more effectively than any biographical narrative – is the omnivorous innocence of Mailer before he fell into notoriety. “I was psychopathically marooned in the present,” as he put it to Diana Trilling in 1960. After this the letters become those of a man keeping his powder dry so that he could save himself for his audience. While not perfunctory, never again would they overflow with such an ecstasy of perception and raw invention.

Anyone familiar with the personal essays will know where Mailer siphoned that energy. With their unguarded directness, the letters allow us access to his naked thought, unshrouded by his often byzantine prose. The present volume is the ideal companion to Mailer’s final anthology, 1998’s The Time of Our Time, a career-spanning retrospective in which the writer arranged each piece “in accordance with the year it refers to rather than the year in which it was written”. Selected Letters of Norman Mailer can stand beside it – or, perhaps more fruitfully, behind it, providing the asides and stage whispers that shape the life and career into a compelling theatre of the creative self.

• To order Selected Letters of Norman Mailer for £21 go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846.