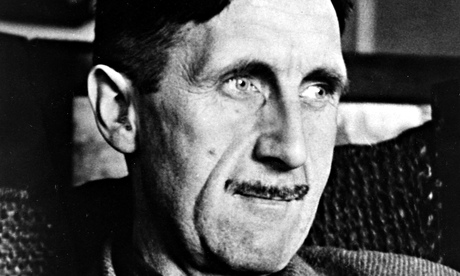

George Orwell is “the supreme mediocrity”. His texts are “lacklustre”. He plays to “the dull and cack-handed gallery”. Nineteen Eighty-four is overrun with “obvious didacticism”. He has “little originality”.

But don’t shoot me! I’m just the messenger. Those quotes – as fans of internet flame wars will already know – come courtesy of Will Self, who slaughtered one of our most sacred cows on Radio 4’s A Point of View in August.

This attack on St George of Orwell met with near-universal opprobrium and derision. Partly because people didn’t agree with Self’s ideas about Orwell’s strictures on simple language, or didn’t think that Orwell could be anything other than a great writer. But mainly because people just didn’t want to hear it from Will Self. Most of the criticism against the article was personal. It tended to focus on the idea that Self swallowed a thesaurus sometime around 1992 and has been burping chunks of it up ever since.

This makes me slightly nervous about what I feel duty-bound to admit having just re-read Nineteen Eighty-four. So before I make my confession, let me wheel on another writer who might bolster my case – and who is less likely to feature in the internet equivalent of the Two Minute Hate.

This noted prose stylist writes that:

During the last 50 years there has been a whole series of writers – some of them are still writing – whom it is quite impossible to call ‘good’ by any strictly literary standard, but who are natural novelists and who seem to attain sincerity partly because they are not inhibited by good taste.”

This author then goes on to highlight a book called We, the Accused by Ernest Raymond and says:

Perhaps it even … gains something from the clumsy long-winded manner in which it is written; detail is piled on detail, with almost no attempt at selection, and in the process an effect of terrible, grinding cruelty is slowly built up.”

He chooses Uncle Tom’s Cabin as the “supreme … good bad book”. “It is an unintentionally ludicrous book, full of preposterous melodramatic incidents; it is also deeply moving and essentially true.”

I’m sure you’ve already guessed that the man writing about good bad books was George Orwell. But doesn’t that last sentence also apply to Nineteen Eighty-four?

Nineteen Eighty-four may even be a great bad book. But it is still “unintentionally ludicrous” and “full of preposterous melodramatic incidents”.

Think, for instance, of the scene where Winston and Julia visit O’Brien at his house. Is that not pure pantomine? The fact that the trap is obvious – and inevitable – is part of Orwell’s point, but you still feel like screaming out: “Look behind you!”

Think also of the scene where Julia first contrives to get a note saying “I love you” into Winston’s hand, even though they’ve never spoken, and based upon an elaborately staged accident with a pre-broken arm. Isn’t that preposterous? And doesn’t Julia’s character go on a curious arc? She is briefly a sharp and collected independent spirit, but soon morphs into a thoughtless, near-silent sex object, and ends up a hopeless submissive. No interest at all is shown in her inner life. If we are to believe that Winston loves her, shouldn’t he also care about what she thinks?

As for “clumsy” and “long-winded”, where “detail is piled on detail”, couldn’t that criticism also be levelled at some of the explanations of party lore, at O’Brien’s lectures to Winston, and especially at the great long extracts from the rebel book that Winston reads to Julia. I know there is superb political analysis in here too, and it creates a fascinating overview of a terrible – but not impossible – world. But didn’t you also feel more than a little sympathy for Julia drifting off to sleep while Winston read?

While I’m putting the boot in, I should also aim a swift kick at the cockney prolespeak: “Steamer … Look out, guvnor! Bang over‘ead! Lay down quick!” Lord love a duck!

Finally, to return to Self, is anyone prepared to deny that Nineteen Eighty-four is not full of “obvious didacticism”? Perhaps there’s also an obvious defence there. What else do you expect from a book about the horrors of a surveillance state and political corruption? Isn’t its crudity part of the point?

And that brings me back round to the good part of the equation. Because, of course, there’s plenty to recommend Nineteen Eighty-four. You only have to look at the way it has altered our language, and raised our collective consciousness of the dangers of the surveillance state. You only have to read the testimony of people from eastern Europe and North Korea who have cited Nineteen Eighty-four as a novel that might almost be documentary. As a work of art, too, there’s power. Just to give a few quick examples, it’s a lesson in the creation of oppressive atmosphere in its physical descriptions of drab bombed-out London, and in the terrifying Ministry of Love.

I could have listed many more virtues. I could even have said: “It is also deeply moving and essentially true”. And I’m sure everyone reading this can think of plenty of other positives. It’s lasted 60-odd years and I’m sure it will endure for plenty more.

But it’s also a big enough book to take a bit of criticism. Perhaps, we could even say that its faults are part of its greatness. That it could combine so many literary flaws with such great impact is mighty impressive. It must surely be possible that the book can be both mediocre and brilliant, deeply flawed and enduringly great?

Or is that doublethink?