TS Eliot maintained that "the more perfect the artist, the more completely separate in him will be the man who suffers and the mind which creates". The black box and the air crash. Objectivity and a torment of twisted metal. But there are many differing degrees of separation, and the story told by this latest volume of Eliot letters is the separation of the dapper man of letters from the agonised individual, whose paranoid, delusional wife, Vivienne, is under suicide watch at the Malmaison sanatorium in Paris.

We glimpse Eliot watching the boxing from Lady Rothmere's box at the Albert Hall. We see him dispatch Emerson ("set up a new standard of Ignorance in America") and Santayana ("a poseur"). He puts the boot into Bertrand Russell: "All the reasons you advance [against Christianity] were familiar to me, I think, at the age of six or eight… Why don't you stick to mathematics?" He drinks too much of Harold Monro's excellent whisky. He is learning to drive. He gossips with Virginia Woolf and drinks six cups of tea. They play the gramophone. He teaches her "what little I know about the Grizzly Bear, or the Chicken Strut". He watches Ernie Lotinga, "the greatest living British histrionic Artist, in the purest tradition of British obscenity". He sings "too much" at a Criterion dinner in a private room. And all the time, Vivienne is going unsteadily mad: "I am in great trouble, do not know what to do. In great fear."

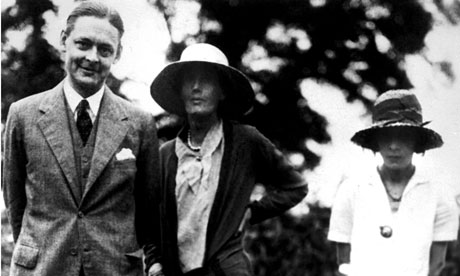

This latest volume (edited by Valerie Eliot and John Haffenden with unblinking attentiveness to the reader's every need) covers the years 1926 and 1927. In this period, Eliot falls to his knees in St Peter's, Rome, to the astonishment of his companions; is privately received into the Church of England; becomes a British citizen; and fails to get into All Souls because some fellows ("sons of the manse") denounce his poetry as "obscene and blasphemous". He acts as executor of his father-in-law's will and negotiates probate. As editor of the Criterion, he solicits reviews, manages an enormous correspondence, soothes prickly contributors and tries to make the magazine a going concern. (The sales average between 700 and 800 copies per issue.) By the end of 1927, his backer, Lady Rothermere, has pulled out, but the magazine manages to struggle on: her gold-plated stupidity and her brisk, cheerful tactlessness are amply illustrated. This is one narrative, the story of Eliot the exceptional juggler, sorting and sifting, capable of coping with a hail-storm of commitments.

The other, darker story shows Eliot standing in a shit-storm, buffeted and barely upright. Humbert Wolfe: "I can't understand how a body so thin and white goes on living." Aldous Huxley: "I lunched with Tom who looked terribly grey-green, drank no less than five gins with his meal." Eliot himself was grimly bemused: "It often seems to me very bizarre that a person of my [Unitarian] antecedents should have had a life like a bad Russian novel."

Now and then, Vivienne emerges from her troubled sense of persecution, the hallucinatory voices swarming in her head. Eliot's niece Theodora has tea with her in Paris and spiritedly opposes the family tendency to deplore Eliot's disastrous marriage: "Aunt Vivien [sic] whom I like better every time I see her. She is a dear & so absolutely wide awake & very bright."

Theodora thinks Eliot may have gained from the marriage. (This is bound to be true, considered artistically. In Ulysses, Stephen Dedalus says: "A man of genius makes no mistakes. His errors are volitional and are the portals of discovery." This is Eliot's version in 1916: "I have lived through material for a score of long poems in the last six months." All good writers know that even disaster, especially disaster, is material.)

More often, though, Vivienne was incapable of separating her troubled personality from her social self. Her spasmodic appearances were tainted by her inner turmoil. Included here is Osbert Sitwell's vivid, unforgettable, previously unpublished account of a wary, tense evening chez Eliot, with James Joyce and Nora, Geoffrey Faber and his wife, Enid, as guests. The atmosphere is one of dutiful jollity. Vivienne is understudying the role of Banquo. Enid Faber tells her the evening has been "lovely". "Vivien looked at her mournfully, and replied, 'Well, it may have been lovely for you, but it's been dreadful for me.' Mrs Faber, rather at a loss, rapped out at her, 'Nonsense, Vivien, you know it's been a triumph.' Vivien repeated in desolate tones, '"A triumph"!... Look at Tom's face!'"

Given Vivienne's baleful behaviour, her affair with Russell, her general impossibility, it is an unsurprising surprise that one of Eliot's letters confesses unequivocally to adultery. He is pre-empting a charge of excessive puritanism: "I remember also minor pleasures of drunkenness and adultery…"

There are two controversial things. One is the epic of facetiousness about "a race of comic Negroes wearing bowler hats" – including some racist, obscene poems that easily offended readers will find offensive. I think it is allowable comic licence – knowingly transgressive like Lotinga, whom Eliot was taken to see by his Jewish friend Jack Isaacs. One of many examples of Eliot's warmth to Jews: "A few weeks ago I saw Horace Kallen, Shef's Jewish friend, whom I like…" In 1951, we learn, Eliot writes a supportive reference for an Italian Jew, Leon Vivante, who left Italy "after the promulgation of the anti-Semitic legislation". Ah yes, antisemitism. In a letter about "the German Jew, Lion Feuchtwanger", Eliot writes: "I simply put it to you whether the appearance of a new book by the same person makes necessary a consideration of his work. I am always prejudiced against such people, but I have never read anything by this man." Eliot's adversaries will read this as an admission of antisemitism. Others will read it as a prejudice against literary incontinence, against polyphiloprogenitiveness.