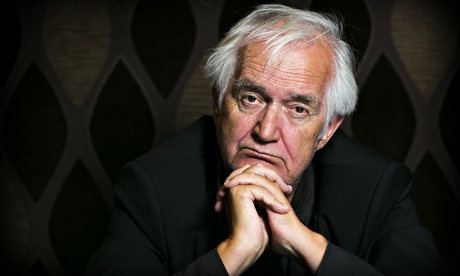

Twelve years ago, when Henning Mankell published the first of his Inspector Wallander novels, he could not have imagined how successful they would be. In his native Sweden the series was to triumph spectacularly and he has sold more than 20 million books worldwide; Wallander outsells Harry Potter in Germany and is top of the book charts in Brazil. Ruth Rendell, who is half Swedish, has read all nine in the original. She admires their edgy, convincing police work and social concerns. "There's a belief that crime fiction should be about little old ladies solving murders in country villages," she says. "But Mankell is modern, and he makes you reflect on society." Questions of responsibility and morality - of justice and democracy - are explicitly raised, which is unusual in detective fiction. "I work in an old tradition that goes back to the ancient Greeks," Mankell says. "You hold a mirror to crime to see what's happening in society. I could never write a crime story just for the sake of it, because I always want to talk about certain things in society." He says the best crime story he has ever read is Macbeth - "a terrible allegory about the corrupting tendency of power that could equally be about President Nixon".

Mankell cites John le Carré as another key influence and admires the way he develops George Smiley with each subsequent book. "If you can call Le Carré a crime writer, he investigates the contradictions inside man, between men, and between man and society; and I hope to do the same. Sooner or later a crime writer will get the Nobel prize (not me - I'm Swedish) because the old snobbery against the genre is fast vanishing." In Sweden, the Wallander mysteries are reportedly read by the prime minister and half his cabinet, as well as by the judiciary.

Now 55, Mankell divides his time between Sweden and Mozambique, where he runs a theatre company. As well as thrillers, he has written children's books and novels on African themes. In Sweden one of his most faithful admirers is Ingmar Bergman: Mankell is married to the film director's daughter, Eva.

Detective fiction from Scandinavia has been fashionable in Britain for some time. The trend was set in 1994 with Peter Høeg's Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow. This Danish thriller radiated an unfamiliar polar chill, but it was Mankell who truly opened the door for Nordic crime. He has been followed into English translation by other Scandinavian thriller writers such as Karin Fossum and Eva-Marie Liffner, Norwegian and Swedish respectively. Seemingly, literary detection is drifting to chillier parts. Marcel Berlins, the author and legal commentator, says: "If you think about it, these Scandinavian whodunits are really quite British. Of course there's something new and strange in them for Anglo-Saxon readers, but they're also curiously, comfortingly familiar. The morose and grumpy Wallander is a sort of Baltic Inspector Rebus. And the flat, monotonous landscapes in these euro-thrillers remind one of Norfolk."

Kurt Wallander remains one of the most impressive and credible creations of crime fiction today. Mankell portrays him as a sternly pensive slogger with health problems. From his first appearance in Faceless Killers, published in Sweden in 1991, the fortysomething detective is in a bad way. He eats too many take-aways and has put on seven kilos in the three months since his wife Mona left him. He has been stopped by his colleagues for drink-driving, and his grown-up daughter Linda has attempted suicide. If that is not enough, Wallander's 80-year-old father (a landscape painter with "7,000 sunsets" to his name) appears to be declining into dementia.

Miserably divorced, Inspector Wallander contemplates a spell in a health spa but prefers to drink more whisky and falls into lugubrious talk of his (and humanity's) demise. Often he wonders if he should be a policeman at all, but stoically pushes on with his investigations into murder, child abuse, drug-smuggling and racial violence. By the eighth novel, Firewall (1998, to be published here next year), the stress and strain of detective work have taken their toll. Earlier in his career, Wallander had been sued for police brutality and accidentally shot a man dead in the fog. Five years on, he retains a degree of disabused integrity but is no longer Kurt the good-humoured gumshoe: he is diabetic, alcoholic and more pessimistic than ever about Sweden's uncertain future. "We're living in the age of the noose," he despairs, "fear will be on the rise."

For many in Britain, the Wallander thrillers appear distinctly Scandinavian in their Strindbergian gloom and bleakness. Yet Ebba Segerberg, one of Mankell's English translators, disagrees.

"The Wallander books may draw from a general Swedish depressive tendency, but I'd say that Mankell's 'gloom' has much more to do with the ordinary (as opposed to Strindbergian) Swedish experience: that is, with an ageing, weight-gaining, balding Swedish male in contemporary, multi-cultural Sweden." Laurie Thompson, editor of the Swedish Book Review, based in Wales, insists that Mankell has comic gifts and maintains that even Strindberg had his jocose side: "So let's not get bogged in the Scandinavian gloom cliché: Mankell deserves better than that."

Wallander is a lovable sleuth in his dour way, and his investigations have a mordant comedy of their own. "No one I know who has discovered him can resist him," says Alexandra Shulman, editor of Vogue and a fan. The novelist Maggie Gee is similarly entranced. "I'm seduced by the leisurely, layered craft with which Mankell establishes the humanity of his policemen - not just Wallander, but his supporting cast of shambolic squad members - through their colds and stomach aches, their cheap cars, which break down when they need them, their failing eyesight and needy families." Taken together, Gee adds, the Wallander mysteries have the "density and pleasurable authority of a 19th-century novel".

For others, what makes Mankell such a compelling writer is his political edge. Wallander's Sweden is a country whose time has passed; behind the roseate flush of its social-democratic prosperity lies a deepening corruption, where justice may not prevail. The books are haunted by the murder in 1986 of Sweden's prime minister, Olof Palme. The failure of the authorities to find Palme's killer has created a "dangerous scepticism" about the Swedish justice system and state institutions in general, says Mankell. As a "humanitarian socialist", he believes passionately in "solidarity" among people, and the Wallander books are an expression of that belief. Yet even Mankell could not have foreseen the catastrophe of September 10, when Sweden's foreign minister Anna Lindh was murdered while out shopping in Stockholm. Sweden's vaunted open society appeared to have taken another fatal blow, but as Mankell told the Observer afterwards: "Maybe to keep an open society, we have forgotten that you need to lock some doors."

Mankell can appear self-important in person, even prickly. Certainly he has an imposingly dry manner in conversation, and fields questions professionally. "Henning has a ruthless quality," his Stockholm publisher of 30 years, Dan Israel, concedes. "If you ask any Swede living in Mozambique if they ever see him there, they say no, because Mankell's always, always writing. His writing is all that matters to him." But others have been favourably impressed by Mankell in person, among them the British crime writer Minette Walters, who met him in Oslo in 1993 during Norway's Paaskerkrim (Easter crime) season. "He was thoughtful, dedicated, charming," she recalls.

Mankell was born in Stockholm in 1948, into a stolid bourgeois household. A year after his birth, however, the family broke up. "My mother did what many men do," Mankell says. "She left." So Mankell was brought up, with his older sister Helena, by his father. In 1950, soon after his divorce, Judge Ivar Mankell moved his family north to Härjedalen province in central Sweden, once part of Norway. The family was now living in a provincial backwater with bears and "Christmas tree forests". As soon as propriety allowed, Ivar Mankell's ex-wife remarried, taking her youngest child, Gustav, to live with her in Sollefteå, due north of Härjedalen. (Gustav was sent back to his father as soon as he started school.) Eventually Mankell's mother returned to Stockholm, where she helped to compile the Swedish National Biography. Mankell did not see her regularly until he was 15.

Clearly the move to Härjedalen was a watershed for Mankell, though he was barely two at the time. Gossip about his "cuckolded" father spread quickly in Sveg, the village where he worked. "At school on Mother's Day we children were supposed to write letters to our mother, but we didn't have a mother, so we had to write to our grandmother instead. It made me feel a little awkward," recalls Helena Mankell. Grandmother Mankell was vital to Henning's formation as a writer; a widow, she had been invited to live with the family in Sveg and it was she who taught Henning to write. Mankell describes his excitement at forming his first words: "I was six at the time and can still remember the miracle that I could make a sentence, then more sentences, telling a story." He adds: "The first thing I wrote was a one-page summary of Robinson Crusoe , and I'm so sad I don't have it any more: it was the moment I became an author."

Though cold and remote, in many ways Härjedalen was a "wonderful place" in which to grow up, says Mankell, and he looks back on those dark winter days as among the happiest of his childhood. His latest book to be published in Britain, The Return of The Dancing Master (not a Wallander procedural), is set in H#228;rjedalen's vast pine forests. The Mankell siblings lived in a flat above the law courts where their father was judge. Court was in session each Monday, and the children had to be quiet, though occasionally they were allowed in to watch. One day an orderly hurried upstairs to ask little Henning if he could borrow his toy cars. They were needed to demonstrate how a traffic accident had occurred, and Mankell was thrilled to be able to help. Another time, the children's school holidays were prolonged as their father investigated a local murder. "Ever since I was a child I have been interested in the justice system and how it works," Mankell remarks.

Mankell speaks of his father as a "kind, strong man", whose first love was not for the law or crime-solving, but music. Ivar Mankell's ancestors had emigrated to Sweden in the 1700s from the border area between Germany and Denmark. "They were musicians by profession, church organists and violin players," says Henning Mankell. Ivar's father, also called Henning (1868-1930), was a composer, and Ivar founded a concert society in Sveg in his honour: it offered an opportunity for the province to see classical music performed. His philanthropy was typical of Stockholm's moderately progressive bourgeoisie, and not surprisingly his son's books are filled with musical references. Inspector Wallander listens to Maria Callas on the squad car radio and longs to see Berg's atonal masterwork Wozzeck. Mankell is a fan of Miles Davis and Charlie Parker as well as opera. "Sometimes I wish I'd be able to write the way Parker plays," he says.

During his 10 years in Härjeladen Mankell read voraciously. Mungo Park and the African explorers were a "revelation"; the logs that floated down the river behind the Mankell house, he told himself, were crocodiles in the Congo. Today Mankell comments: "Africa was the most exotic place I could conceive of - the end of the world - and I knew I would go there one day." He learned that the imagination could be an instrument, not just of creativity, but of survival. "In my mind I created another mother for myself to replace the one who had gone." This imaginary mother, he says, helped him over come the "crisis of life" and his sense of isolation. "And I think that was me at my best, when the forces of the imagination had the same value as the real world."

In 1961, Judge Mankell moved his family south to Borås, near Gothenburg, where Henning attended secondary school. He was soon bored with the curriculum, however, and left school at 16 to become a merchant seaman. His father, though disappointed, was sympathetic to his son's restless spirit. It was 1964, and for two years Mankell worked as a stevedore on a Swedish ship ferrying coal and iron ore to Europe and America. He loved the ship's "decent, hard-working" community and considers his time at sea his "real university". He says now: "It was a romantic, Conradian dream of escape, though there were long, boring times, too." Mankell visited Middlesbrough 25 times and Bristol 15 times while on shore leave.

After his spell at sea, he settled in Paris in 1966. It was a time of student activism and political debate. The 18-year-old had little money and was often hungry. ("I still don't know how I survived but I did.") He returned to Sweden a year-and-a-half later, in 1968, to embark on a career in the theatre. By the time he was 20, working in Stockholm as a stagehand, Mankell had written his first play, The Amusement Park. It was about Swedish colonial interests in 19th-century South America and not very good, he says, though it was well-received. Ivar Mankell died in 1972 just days before his son went on to publish his debut novel, The Stone-Blaster, at 24. Mankell is proud of the book. "It concerns an old man looking back on his life and on Swedish society and the need for solidarity." The novel is still in print in Sweden, though it has not yet been translated into English. Mankell says his father always believed in him and knew he would have success as a writer.

Meanwhile Mankell had not forgotten his dream of Africa. By the winter of 1972 he had saved enough money as a stagehand to go to Guinea-Bissau (still a Portuguese colony). "I don't know why, but when I got off the aeroplane in Africa I had a curious feeling of coming home." Mankell continued to visit Africa and in 1987, after settling briefly in Zambia, he was invited to run the Teatro Avenida in Mozambique's capital Maputo. His personal life had become fairly complicated by now. Over the 15 years since he first visited Africa, Mankell had had several affairs in Sweden. Today he is reluctant to talk about this period of his personal life, though he is happy to admit to the existence of four sons - Thomas, Marius, Morten and Jon - by "previous relationships". Mozambique, he adds, was partly an escape from domestic ties. The African republic was then in the midst of civil war and Mankell's plane "crash-landed" amid gunfire. At the Teatro Avenida he had to start from scratch as there is no tradition in Mozambique of professional theatre.

Mankell has now spent more than 20 years in Africa and says the continent has made him a "better European"; it gives him a perspective and literary distance. He wrote half the Wallander mysteries in Africa and his award-winning novel, Comédia Infantil (1995), about a prophetic street child, is set there. Curiously, Mankell regards Shakespeare as "quite an African" author (Hamlet, he believes, could be performed as an "African kingdom saga") and the "next Shakespeare", he adds, may well be an African. Mankell admires the Mozambican writer and poet Mia Couto, who lives near him in Maputo.

Inspector Wallander's debut, Faceless Killers (1991), was written in response to the social chaos Mankell encountered on his return to Sweden in early 1989. Neo-fascist attacks on immigrants had increased during his two years in Mozambique. "Racism is a crime, and I thought: okay, I'll use the crime story. Then I realised I needed a police officer." He plucked the name "Wallander" out of the telephone directory. "It was May 20 1989 (I looked it up in an old diary) when Kurt was born."

All nine Wallander mysteries are set in the flat farming landscape of Skåne (pronounced "Skorner"), on the southernmost tip of Sweden. Mankell has kept a farm there since the early 80s and likes the blustery, treeless landscape. "It makes a change from Härjedalen. Skåne is the place where Sweden ends - a sort of Baltic Texas." He adds: "Border areas have a dynamism all their own: they set off a reflex of unease."

Inspector Wallander's home town of Ystad stands in windswept grassland, where buzzards and other raptors circle. According to Rendell, the Wallander stories are, among other things, "landscape novels", bleakly fixed in Baltic geography. She reflects: "I don't think English readers realise just how important landscape and natural history are to Swedes: I mean, spring's an almost ecstatic event to them." For Rendell, the Wallander books have a "dream-like" landscape that is recognisably Baltic, but could also be anywhere in northern Europe, "and I find this very potent". AN Wilson, writing in the Daily Telegraph, said the Skåne terrain is increasingly part of one's enjoyment of the Wallander series. "The bleak weather, the featureless but haunting rocky fields ... are so well evoked that they form movies in our heads."

To Mankell's faint embarrassment, Ystad now offers guided tours of Wallander country. German tourists descend on the Ystad police headquarters and photograph each other standing in the long corridors. One policeman there, Inspector Kurt-Ingvar Wald, is routinely approached for his autograph: his name is a homonymous near-miss to Kurt Wallander's. ("Yes, I've heard about him," Mankell says wearily.) The entire Ystad police force have read the Wallander books, says Chief Inspector Kent Persson. "If they're sometimes a bit exaggerated, it was a stroke of genius to set them in Skåne." He explains: "Skåne is closer to Poland than Stockholm, and criminals from the Baltic states have brought in drugs across the sea. The only thing we don't have in Ystad yet is prostitution." Otherwise, any crime that occurs in Stockholm also occurs in Ystad.

Until recently, Wallander was more famous than his creator. "Henning didn't like to participate in TV debates or do book signings," says Israel, "therefore he just wasn't in the public eye." The third Wallander novel, The White Lioness (1993), changed all that. Set partly in South Africa, the book was published in several different countries simultaneously and, says Mankell, "blew out the gates". Afterwards the author began to receive letters addressed to Inspector Wallander and was even asked how his detective would vote in the EU referendum. "It is like in London, you still get letters to Baker Street, Number 221b." Mankell's sleuth, like Sherlock Holmes, has assumed a life of his own. In Britain, to the annoyance of some readers, the Wallander books have been published out of seqence, though Mankell says it doesn't matter. "Yes, they were written in chronological order, but each one stands on its own I think."

Mankell says he would not care to be Wallander's friend. "We share a love of music and a Calvinist attitude to work (I'm a very hard task master), but otherwise we're quite different and I don't like him too much." Indeed, Wallander nurses feelings of guilty puzzlement that his daughter seems to be dating an African. "If Wallander was a leftist, progressive detective, these thrillers would not be half so popular," says Israel. "Really, Wallander's a kind of spokesman for the worries of the common man." He adds: "Henning has an uncanny ability to decipher the signs of the time - he knows how to tap into people's fears and uncertainties."

In Sweden, the nine-book Wallander series is now complete. Mankell says he does not want his readers to feel he is "bored" with his creation, so he has decided to retire his detective. "I did this out of respect for myself and my readers." Latterly, Mankell has embarked on a new crime series in which Wallander's wayward daughter Linda joins the Ystad force. The first of these, Before the Frost (2002), concerns a religious doomsday cult and has sold 450,000 copies in Sweden so far.

Only in America has Inspector Wallander failed to make a significant mark, though he is rapidly gaining a readership. Steven Murray, Mankell's Albuquerque-based translator, says there is not "enough wham-bam or violent shoot-out" for American tastes. Mankell, by contrast, is a strong defender of what he calls the "long novel" and the "virtues" of plot and character. For Gee, Mankell's great strength as a mystery writer is the emphasis he places on procedure and deduction, rather than action. "For much of the time we seem to live inside Wallander's head, and I suppose this interior quality is more often a characteristic of women narrators," she says. Interestingly, the Linda Wallander series is partly inspired by diaries kept by a policewoman somewhere in Sweden - Mankell had contacted a source in the Swedish Police Academy. "She's told me a lot of interesting things," he says, "and there are still many journalists trying to find out who the hell she is!"

Mankell married Eva Bergman in 1998, when he was 50. She is the daughter of Ingmar Bergman's second wife, the dancer Ellen Lundström, and is a choreographer and theatre director. So far she has directed two of her husband's plays. The first, Tale on the Beach of Time (1997), is an African drama about "man and the origins of man"; Mankell had worked on the play, off and on, for 25 years since he first arrived in Africa. He and Eva spend summers together on Ingmar Bergman's island retreat of Fårö in the Baltic Sea, where Hour of the Wolf and Persona were filmed. The landscape there, with its flat stony heaths, reminds Mankell of Africa.

In Africa, Mankell is passionately committed to the fight against Aids and devotes much of his spare time to his "memory books" project, which aims to raise awareness of the catastrophe. Parents with Aids are encouraged to record their life stories not just for their children, but as a human chronicle as well. "Maybe in 500 years these books will be a great record of African times," says Mankell, who hopes to store them eventually in the new Alexandrian library in Egypt. Among Mankell's African books published in English are two powerful short novels for teenage children, Secrets in the Fire (1995) and Playing with Fire (2001). These chart an African girl's survival after a landmine blast, and to Mankell's great pride are now on the Swedish school syllabus. Henning Mankell, the most internationally famous Swedish writer since Strindberg, is now part of the canon.

Henning Mankell - life at a glance

Born: February 3 1948, Stockholm.

Educated: Folkskolan elementary school, Sveg; Högre Allmäna Läroverket, Borås.

Married: 1998 Eva Bergman.

Career: 1964-66 merchant seaman; 1987- director Teatro Avenida, Maputo, Mozambique.

Some books in English: 2000 Faceless Killers; 2000 Sidetracked; 2001 The Fifth Woman; 2001 The Dogs of Riga; 2002 One Step Behind; 2003 The White Lioness; 2003 Secrets in the Fire, The Return of the Dancing Master.

Some honours and awards: 1991 Swedish Mystery Academy Prize; '99 German Crime Prize; 2001 Macallan CWA Gold Dagger Award; 2002 Author of the Year, Germany.

· Henning Mankell's The Return of the Dancing Master is published this week by Harvill at £14.99.