Deep in the heart of northern Norway lies the Kjølen mountain range, a series of jagged peaks that line the Swedish border. This bleak Arctic wilderness, more than 100 miles from any major hospital, may seem an unlikely setting for an event that changed medical history but, 14 years ago, the miraculous survival story of Anna Bågenholm for ever redefined our understanding of the boundary between life and death.

Bågenholm, a trainee doctor, was skiing off-piste with two of her colleagues when she lost control during a steep descent, falling on to a layer of ice covering a mountain stream. A hole opened in the ice sheet and she was dragged head-first into the freezing meltwater. Trapped hopelessly beneath eight inches of ice, she was slowly freezing to death.

Normally your core body temperature is 37C but with immersion in ice-cold water, this plummets rapidly. Below 35C, the body enters the state of hypothermia, characterised by shivering and pale skin. Below 30C, most victims will lose consciousness and, when body temperature drops to 25C, cardiac arrest will almost certainly occur.

Although Bågenholm's friends immediately called for aid, it would take an hour and a half for a mountain rescue helicopter to reach their location. After 40 minutes of desperate struggling, Bågenholm's body went limp. Shortly afterwards her heart stopped.

Following cardiac arrest, the body enters a state known as "downtime". This is the twilight zone in which the process of dying begins. Normally within a few minutes of downtime, without immediate medical intervention, death will follow.

By the time Bågenholm was brought to the University Hospital of North Norway in Tromso, her heart had stopped for well over two hours. Her core temperature had plunged to 13.7C. She was in every sense clinically dead.

However, in Norway, there has been an old saying for the past three decades that you're never dead until you're warm and dead. Mads Gilbert is the head of emergency medicine at the hospital and, from experience, he knew that there was a slim chance the extreme cold had actually kept her alive.

"Over the last 28 years, there have been 34 victims of accidental hypothermia with cardiac arrest who were rewarmed on cardiopulmonary bypass and 30% survived," he said. "The key question is, are you cooled before you have the cardiac arrest or are you first having a circulatory arrest and then getting cooled?"

While lowering the body temperature will stop the heart, it also reduces the oxygen demand of the body and, in particular, the brain cells. If the vital organs have been sufficiently cooled before the cardiac arrest occurs, then the inevitable cell death from the lack of circulation will be postponed, buying emergency services an extra time window to try and save the person's life.

"Hypothermia is so fascinating because it's a double-edged sword," Gilbert said. "On the one side it can protect you but, on the other side, it will kill you. But it's all a question of how controlled the hypothermia is. Anna was probably cooled quite slowly but efficiently so that, when her heart stopped, her brain was already so cold that the oxygen need in the brain cells was down to zero. Good CPR can provide up to 30-40% of the blood circulation to the brain and in these cases that is often sufficient to keep the person alive for sometimes seven hours while we try to restart the heart."

Crucially the levels of potassium in Bågenholm's blood were normal, a key indicator of the extent of cell damage in the body and the decision was taken to warm her up. If the potassium is beyond a certain threshold, the person has no chance of survival.

Four and a half hours after Bågenholm first fell through the ice, her heart was successfully restarted. She spent 35 days on a life support machine before being moved to intensive care and then a rehabilitation unit. From there, she began the slow process of training herself back to complete restoration.

Her extraordinary story has led to therapeutic hypothermia being introduced as a protective measure for victims of strokes, liver failure and epileptic seizures. Recent studies have also illustrated its effectiveness in newborn babies who have suffered a lack of oxygen at birth.

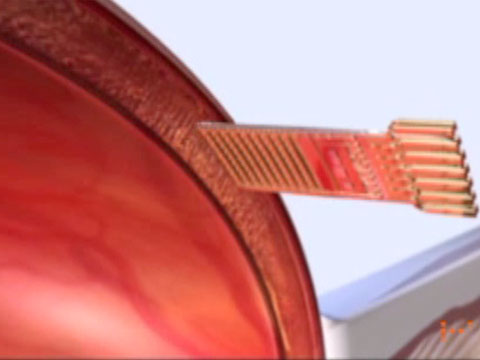

It is commonly used around the world in open heart operations where surgeons will cool the body down to as low as 10C, allowing them to cut off the arterial supply to the brain for up to 15 minutes without any notable brain damage.

Jasmin Arrich, of the Medical University of Vienna, researches the use of therapeutic hypothermia during or after resuscitation from cardiac arrest.

"In these cases, the patient's body is cooled down to mild hypothermia (32-34C) for 12-24 hours," she said. "We do this because when this patient can be resuscitated and the circulation starts again, various pathophysiologic mechanisms are initiated and substances are formed that continuously keep on damaging the brain cells and other cells of the body. Mild hypothermia exerts its beneficial effects on many of these mechanisms and substances."

However, there has been some controversy over the introduction of therapeutic hypothermia as a mainstream procedure for certain conditions based on unsubstantial evidence. A group of Swedish scientists have released a new paper questioning the levels of hypothermia that are applied as a protective measure to the unconscious survivors of cardiac arrest.

"We have to be careful because hypothermia is also dangerous to the body," Gilbert said. "It is upsetting the enzyme system, the cellular membrane balance and the integrity of the cells. And in trauma, we know there is a linear relationship between the degree of hypothermia in the trauma patient and the mortality rate. The clotting mechanisms are greatly influenced by hypothermia in a negative way. Anna was able to survive for so long because she didn't have a trauma. She didn't have any bleeding anywhere."

Fourteen years on, Bågenholm now works as a senior radiology consultant in the very hospital where her life was once in the balance. Nobody before or since has been so cold and lived to tell the tale. These days, she once again partakes in extreme skiing in the mountains of north Norway, a living reminder of the human body's capacity for endurance.